Old School Words Today's Gamers Won't Understand

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Video games have only been a major thing since the '80s. But since that time, the way we talk about them has changed drastically. Here are some old-school words and terms that younger, newer gamers probably never experienced, and will only hear about in whispered tales of the distant past.

Bits

Today's consoles are defined with so many different specs — storage size, memory, CPU, GPU — somebody only half-listening would probably think you're discussing the latest laptop from Apple or HP. But there's one spec that nobody talks about anymore, even though it used to be the beginning and end of console discussion: data bits.

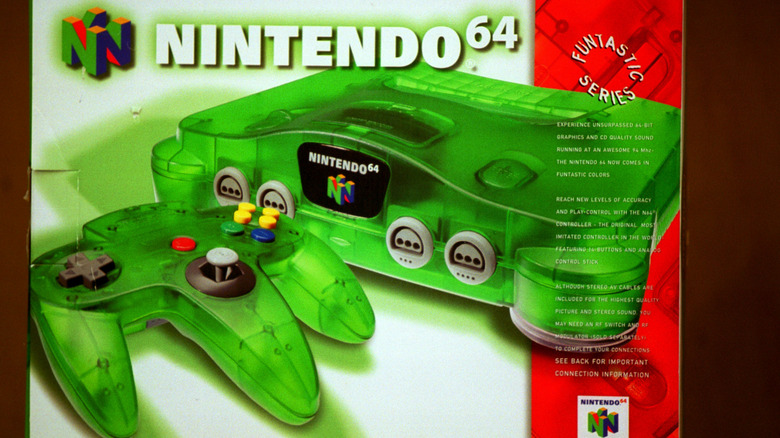

When the original Nintendo Entertainment System came out, it was an 8-bit system, much like the Atari 2600 and 5200 were. But then came the Sega Genesis. That console was 16 bits–twice as many bits!–and gamers' jaws dropped. Nintendo soon followed suit with their own 16-bit system, and begun the Bit Wars had. Each generation of systems had more bits than the last, and it was a major selling point for your system to have more bits than the competition. Nintendo wouldn't have called their 64-bit system the Nintendo 64 if they didn't think that gigantic number would draw huge bucks, after all.

Some companies tried to do things out of order, like when Atari unveiled the 64-bit Jaguar while Nintendo and Sega were still largely in 16-bit land. That might've worked, except the Jaguar was basically terrible–proof that bits still needed good games backing their hype up. Eventually, however, focus moved away from bits, as they were mostly an indicator of how many colors a screen could display at once. Specs that actually affected hardware and memory became more important and the PlayStation 2, Gamecube, and Xbox sporting 128 bits was about as important as the presets on the new car you want to buy.

Continues

Unlimited lives and checkpoint-continues haven't always been the norm. For a long time, games offered a set number of lives and continues, and if you croaked through them all, say hello to stage one. Again.

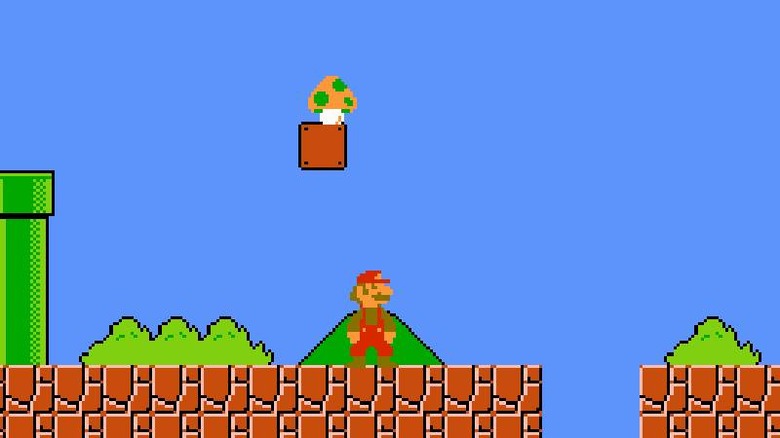

For the first few generations of video games, most titles gave you a set number of lives, usually three. If you lost them all, you might have been allowed to continue at the start of whatever stage you died in, but once you blew through all your continues, the game decided you were terrible at playing it, and punished you by sending you to the very beginning to try again. Some games were extra unforgiving, offering three lives and no continues, or sometimes only one measly life sans continues. It was a holdover from the arcade game days, when the primary goal was to tempt you into breaking up with your quarter collection. The easiest way to do that was to give you a minimum number of opportunities to win. If you didn't, then you either paid up to play some more, or went home to read a book.

In recent years, the game industry has finally gotten this way of thinking out of their system, and have no problems with gamers happily playing for hours and continually progressing toward their goal, no matter how awful they may be at the whole enterprise. After all, if they actually enjoy playing your $60 game, they might be inclined to pay another $60 for your next one.

Fog

In games like Skyrim and Witcher 3, you can see the world around you for miles — even distant mountains are as gorgeously detailed and rendered as the land and people right in front of you. That wasn't always the case, as old-school fans who dealt with endless fog remember all too well.

During 3D gaming's awkward adolescent phase, consoles didn't have the horsepower to handle detailed backgrounds. So they had two choices: ugly, clippy backgrounds, or no backgrounds at all. Many games chose the latter, blanketing themselves in thick layers of fog to disguise how, past the point of action, there wasn't anything to see. As you advanced, the fog around you would magically disappear, but you could no longer see where you once were, and the places you still had yet to visit were as obscured as ever.

Some games made fog part of their narrative, rather than just expecting you to accept it. Silent Hill, for example, made the fog part of an alternate reality you step in, aptly called the Fog World. There, you had to rely not on sight, but rather sound to find the monsters before they found you. Likewise, Superman 64 explained its green fog as "Kryptonite Fog" designed by Lex Luthor to screw with Superman. Most games, however, just gave you a foggy world and assumed you'd like that more than the alternative.

1-Up

Back in the day, when gamers had limited lives and maybe one continue to tide them over, finding a 1-Up was more welcome than a $100 bill on the sidewalk. Anytime you got that extra chance to win and not get sent back to the beginning for once, you would take it.

In many early arcade games, you earned extra lives by scoring more and more points. Later games, like Super Mario Bros., tweaked that to award extra lives if you gathered enough coins (or some other nifty collectible) in each level. What's more, gamers started to find single objects that, if collected, would award them with extra lives. In Super Mario Bros, it was a green mushroom. In Mega Man, it was his own severed head, which wasn't creepy in the least. Whatever the game made the 1-Up look like, it made the player's day when they appeared.

Nowadays, you don't really need 1-Ups, as most games just let you keep playing until you win or rage-quit. Even games that do award extra lives are often designed so you don't truly need them, what with autosaves that kick in every few minutes and make it so you never have to revisit stage one unless you really want to.

Cheat code

Just because an old-school game offered few lives, limited weaponry, and overall little hope of seeing the end credits, didn't mean the gamer had to take it lying down. They could totally cheat if the developers wanted them to, and cheat they did, all with the advent of cheat codes.

These were button combinations the player pressed at various points in the game, though they were usually restricted to the title or stage select screen. Some codes would give you extra lives, others more energy, while others would let you skip to whatever part of the game you wanted to play. Sick of dying at stage eight and getting booted back to the beginning? Put in the correct code, jump to stage nine, and pray it didn't kill you too.

Perhaps no cheat code is more famous than the Konami Code, which worked with just about every classic Konami game. By pressing up-up-down-down-left-right-left-right-B-A-start, gamers would get spoiled more than a Super Sweet 16 birthday girl. Whether it was dozens of lives, extra power, invincibility, a stage select, or some other reward, if it said Konami, and you knew the code, you were going to have a good time.

Game Genie

With few exceptions, most cheat codes were inserted into the games by the developers themselves. For any games developers "forgot" to enhance, old-school gamers turned to a funky little miracle worker called the Game Genie.

Released by the company Galoob for the NES, SNES, Genesis, Gameboy, and Game Gear, the Game Genie was a device you attached to whatever game you were playing, and then inserted into the console. You would then input codes that basically hacked the game and gave you all sorts of goodies. You could have infinite lives, infinite continues, infinite energy, unlimited ammo, super strength, or just jump to any level you desired. Alternately, some codes let you make the game harder, by giving you less energy, fewer lives, or making the enemies stronger. Either way, the game was now yours to mess with.

Some companies hated that, such as Nintendo, who tried to sue Galoob over the Genie. They ultimately failed, as the judge decided that using the Genie did not "create a derivative work," ergo Mario and company just had to eat it and smile. They eventually beat the Genie by making games that didn't require endless codes to actually win, but Galoob was there when gamers needed them the most, and for that we're forever thankful.

Cartridge

For the past quarter-century or so, console gamers have accessed their games in one of two ways: by downloading them, or inserting discs into the system. But before the mid-90s, there was but one way to play a console game: via cartridge.

When games didn't require tons of storage and memory, cartridges were a perfect vessel for the gaming goodness within. Plus, they were big, colorful, and looked awesome when paired with a few hundred of their kin. But as games got bigger, longer, and more sophisticated, the hard reality about cartridges set in: they could only hold so much. Mediums like CDs had far more storage capability, and Sony and Sega knew it. So their 32-bit systems, the original PlayStation and Saturn, respectively, ditched carts entirely and focused on CDs. And for good reason: games like Final Fantasy VIII took four CDs to hold. You'd either need several dozen cartridges, or the ability to stomach a much shorter, uglier game than what we got.

Nintendo was a little slower on the uptake, with its 32-bit system (the Virtual Boy, every masochist's favorite) and the Nintendo 64 both using cartridges. Finally, even Nintendo realized how much they were limiting themselves, and by the next generation of consoles, the GameCube had embraced discs as well. Cartridges now exist mostly for nostalgia, and for younger gamers to gaze upon with awe at their local used-game store.

Blowing into the cartridge

Another problem with cartridges was that, sometimes, they wouldn't work quite right due to dirt and dust gathering inside. Most every old-school gamer knew the solution, however: blow into the cartridge and make the dust go away. They knew this thanks to the most bulletproof of scientific sources: their older sibling told them a kid did it and it totally worked.

The thing is, blowing actually did work! Sometimes! In reality, it was actually a crapshoot whether it would get the game going or not, but for some reason, many gamers would ignore the times it didn't work and focus on the few times it did. And so, the cart-blowing solution remained the preferred operation for frustrated gamers everywhere. But do you know why it only sometimes worked? Because it actually didn't work at all, and your sibling's friend was a big dumb liar the whole time.

In 2014, PBS Digital Studios released a video examining the cart-blowing phenomenon, concluding that the act of blowing was nothing but a placebo. In fact, it might have actually made problems worse: Nintendo itself warned against blowing into cartridges, saying it "can corrode and contaminate the pin connectors." So what does work? The simple act of taking the game out of the system then putting it back in. The simplest solution was the right one all along, and we could've saved our breath for huffing and puffing after Mario died for the 900th time that day.

Random encounter

Once upon a time, role playing games like Chrono Trigger–which let players see their enemies ahead of time and steer clear of them if they didn't feel like fighting–were actually revolutionary. That's because just about every RPG before that (and plenty after) relied on the "random encounter."

To put it simply, you wandered the game world until the screen flashed and thrust you into battle. Once you won, you started walking again and would find yourself thrust into battle after a certain number of steps. Sometimes you only got one step in before a new set of baddies invited themselves to your sword-and-stab party. Does that sound super-frustrating? Imagine that being the only way to gain experience and get stronger. Kefka was funny, but was he really worth fighting six sets of Delta Beetles in 10 steps?

Today's RPGs wisely ignore the random encounter, in favor of putting all the enemies right in front of you. This gives you ample time to prepare for the fight, or to run away and choose exploration instead. Experience is often granted more through quest completion than grinding through battle after battle, which is so much more satisfying. Honestly, simply being able to take more than two steps in peace is pretty damn awesome.

Rumble Pak

For the longest time, controllers had no vibration — if you wanted a good shake every time your character got hit, you had to do it yourself. But that all changed with the Rumble Pak, perhaps the biggest game-changer in Nintendo 64 history not named Super Mario 64.

The name–bad spelling aside–describes the product perfectly: it was a pack that rumbled, which you attached to the back of the N64 controller. Once powered on, it would react to certain events in your game by vibrating, which made the player truly feel like they were part of the game. If they were playing Star Fox and some jerkhole of an enemy shot at your ship, you'd feel the shakes just as much as poor Fox McCloud did. Outside of wearing big, goofy VR goggles, the Rumble Pak might have been the ultimate in gaming immersion.

So why do you never hear about Rumble Paks anymore? It didn't go out of style — rather, it became so in-style that virtually every post-N64 system made rumbling a built-in feature. Today, controller vibration is as commonplace as analog sticks and crumbs of food stuck in the D-pad grooves. The N64 didn't do everything right, but getting us ready to rumble was a solid A+ with extra credit.

Memory Cards

Nowadays, consoles have so much memory, it's normally no problem to save all your progress right into the system. But for awhile, saving was an actual issue. Cartridges could hold save data, but CDs couldn't. Since the first couple generations of CD-centric consoles had less memory than Forgetful Jones, gamers had no choice but to preserve their progress on memory cards.

Early memory cards, on systems like the PS1, held 15 blocks of memory, allowing you to store up to 15 games' save data at a time. Meanwhile, some games took up multiple blocks because they were just that damn big. By the next generation, blocks were largely eliminated in favor of overall storage space. So if your card could hold 128 MB of data, you had to ration that out for all your games, or buy a second card. And Heaven help you if you lost the tiny things. Few experiences were more soul-crushing than losing 100 hours Star Ocean: Till The End Of Time progress because you absent-mindedly chucked your card in your bookbag and lost it among your unfinished Global Studies homework.

Today's super-powerful consoles don't require cards, since most save data can be contained within the console (or on the Cloud). But for today's discerning gamers, there are external hard drives that, storage-wise, are absolutely enormous. Some can hold up to two terabytes of data — that's 2000 gigabytes, in case you were wondering. Best of all, they're much harder to lose than those dinky little memory cards.

Kill screen

Today, the idea that a game would crash if you progressed too far would be grounds for a boycott. But in the early arcade days, it was the norm to encounter an unbeatable final boss in the form of the game you just paid money to play.

Famously seen in Pac-Man and Donkey Kong — endless games that simply repeated levels until the player died, ran out of quarters, or got bored — the kill screen would occur when a player triggered an "integer overflow." This is where a certain value in the game would run higher than the game's allotted memory. In 8-bit games like Pac and Kong, there was only enough room for 255 values per bit of data, so if a player exceeded that value somehow (by reaching Level 256 in Pac-Man, and by Donkey Kong's bonus calculator reaching 260 after Screen 117), they'd encounter the dreaded kill screen. In Pac-Man, the level completely glitches and fills itself with useless data the poor yellow dot can't possibly navigate. In Donkey Kong, the bug triggers an eight-second time limit guaranteed to kill Mario every time. If Bowser had thought of that, he could've married Peach decades ago.

We don't see kill screens anymore, since games have so much memory. To trigger one, you'd presumably need to reach Level 14 Centillion. But even then, since the game will likely have a final level, as virtually all games do today, it would end before any evil integers force it to.