Terrible Things Video Games Pressured You To Do

Video games have taken us on some spectacular journeys to far away worlds and historic moments we couldn't have witnessed in person, all while letting us do so from the comfort of our own couches. We don't often have to worry about living with the consequences of games given that they don't truly affect reality, but sometimes the moral choices presented to us can linger. There are a lot of games that pressure players with morality and the consequences of our actions, but these moments and choices have stuck with us more than others, for better or worse.

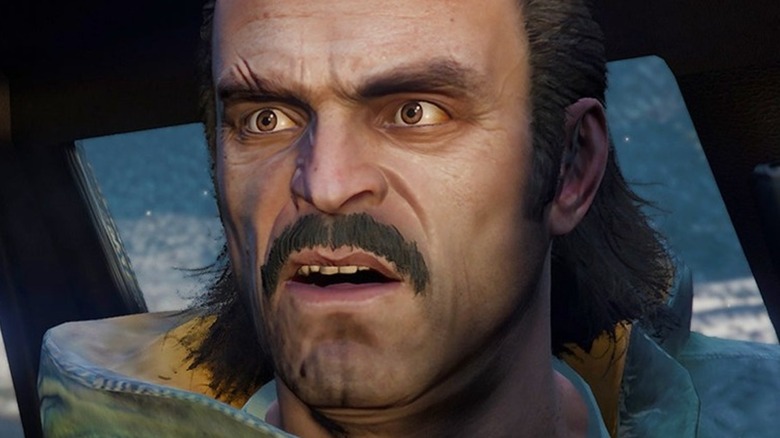

Stuck in the middle with Grand Theft Auto 5

Rockstar Games has never shied away from controversy, and its fan-favorite "Grand Theft Auto" series is a prime example. The series has often pushed the limits of taste and what's acceptable in a video game, with players living lives of crime and vice that would make most real inmates blush. But for all the glamorizing of violence most players enjoyed, there's one moment in "Grand Theft Auto 5" that took things a bit too far even by Rockstar's loose standards.

Around half-way through, players are met with a mission that requires them to assassinate an alleged terrorist. The only problem is, even the government doesn't quite know what the target looks like. In order to discover his identity at a crowded party, players must torture an otherwise innocent man. You can give him an electric shock, whack him with a big wrench, or use pliers to pull out teeth, all so you can get as many details about the target as you can from the subject. And if he happens to be pushed too far before giving up the goods, that's okay. You can bring him back to life with an adrenaline shot.

It's purposefully not an easy scene to complete, but that doesn't make it any less grotesque. In a series full of memorable moments, for good or ill, the torture mission in "GTA 5" proves that just because you can do something outrageous in a video game doesn't mean you should.

Fallout 3 pushes your buttons

Since acquiring the "Fallout" license, Bethesda's take on the series has been chock full of moral quandaries. Decisions you make as a player define the post-apocalyptic world as you explore it, giving each person slightly different playthroughs depending on how they dealt with particular choices. While there are dozens of branches you can explore, the very first major decision not only defines your game, it also defined Bethesda's vision for the "Fallout" franchise.

Arriving in Megaton, you find that the town is built around an active nuclear bomb that failed to detonate years ago. The people all live in shacks hastily built around the bomb site, with only a few fearing its possible explosion. While you explore, Sheriff Lucas Sims asks you to disarm the bomb to keep Megaton safe for the foreseeable future. Of course, his isn't the only offer in town. Just beyond the town's outskirts lies Tenpenny Tower, home to Allistair Tenpenny, a mean old rich dude who wants Megaton erased from the map.

There are no wrong ways to proceed as "Fallout 3" is all about your Karma level. You can be as good or bad as you want, provided you're willing to deal with the consequences either way. Blowing up the town sets you back quite a bit with St. Peter at the pearly gates, but there is something satisfying about pushing that big red button and watching the town go boom.

Wolfenstein 2's sadistic Old Yeller

Machine Games' take on "Wolfenstein" has given the rebooted franchise an actual heart, having developed protagonist BJ Blazkowicz into a fully realized hero instead of a disembodied head. The surrounding cast helps ground BJ into someone that you actually believe and want to rally around for his beliefs, rather than just because the game says he's a hero. That's what makes an early moment in "Wolfenstein 2: The New Colossus" so devastating.

For the first time in the new canon, players are given a glimpse into BJ's early life in Texas. There, we discover young BJ was the child of a strict, racist southern father and a loving Jewish immigrant mother. His father blames all the trouble in the world on BJ's mother, the African-American populace of the town, and everyone else that's not a white man. Mr. Blazkowicz lashes out at BJ and his mother in expected ways, but after learning BJ befriended a young black girl, he snaps.

As punishment, BJ's dad drags him to the basement and puts a shotgun in his hands. The father then lures the family dog into the room, and he directs BJ to shoot the dog. Players can aim away and shoot the wall, but BJ's father still ends the puppy himself, claiming BJ was too weak to be a real man anyway. It's a disturbing snapshot of reality in an otherwise over-the-top game, and one that makes a late-game family reunion that much more meaningful.

A Fable to remember (or regret)

As one of the pioneers of video game morality, the "Fable" series made player choice a major part of each of the franchise's three core games. Though all the "Fable" entries allowed you some semblance of life-changing decisions, it's the final choice in "Fable 2" that has stuck with players the longest.

After battling your way through the world to get to the Spire, your hero finally confronts the villainous Lucien. Here, you get the showdown with the big bad you've been working towards the entire game, and after finishing Lucien off (or letting the Reaver do it for you), the immortal sister of the original game's hero, Theresa, offers you one of three wishes. You can either: bring everyone in the world back to life and sacrifice yourself in the process, bring back your family and dog at the expense of all those souls who worked on the Spire, or take an inordinate amount of money and retire as a hero that everyone in the world hates.

Like so many other morality plays in games, there are no truly wrong choices, but the guilt you'll feel over not bringing all those people back to life may vary. Virtual money is cool and you did do all the heavy lifting to stop Lucien...but if everyone hates you, was it really worth it?

Toeing the line or crossing it in Spec Ops

"Spec Ops: The Line" was a military shooter that went beyond the "oo-rah" focus of so many other similar games. Choosing to focus on the psychological effects of war on the human psyche, "Spec Ops" gave players a look at the gray areas between right and wrong, and often pushed them to act in ways that were effective strategically, but damning mentally. Unlike a number of other games with moral choices, however, "Spec Ops: The Line" didn't let those decisions alter the story or gameplay. They just tested a player's own fortitude.

Primarily a game about rescuing people, "Spec Ops" also has you killing an awful lot of enemies in Dubai. Where some moments in the game allowed you to be more discreet or avoid conflict, one section forced players to commit a war crime in order to proceed. With their backs against the wall and outnumbered by what appeared to be a heavy number of enemy forces, the "heroes" of the game had no choice but to drop white phosphorus on an entire portion of the game world in order to pass through. Only after securing the area does the truth come out, making the characters–and players–feel absolutely sick.

As it turns out, the "enemies" you were chemically attacking weren't really enemies at all, and dozens of unarmed civilians were affected by your actions too. It was already a horrible moment in the game, made all the more sickening by not letting players find another solution. "Spec Ops" had a lot to say about war and what it means to be a soldier, but this was one point we wish wasn't made at all.

How far will you go for your son in Heavy Rain?

In Quantic Dream's "Heavy Rain," Case protagonist Ethan Mars must decide how far he's willing to fall in order to rescue his son Shaun from the Origami Killer. Ethan was faced with five trials to prove his love for Shaun, with the Shark Trial pushing him to his absolute limit. The trial set forth asks Ethan to kill a drug dealer in order to learn where Shaun has been taken by the Origami Killer. The sadistic villain at the center of "Heavy Rain" has put Ethan through a "Saw"-like wringer, testing his will and mental state every step of the way. Killing the drug dealer takes one more thug off the street and gets Ethan one step closer to his son, but it also means taking the life of another man — something even Ethan, and players, aren't sure they are capable of doing.

The outcome of the moment doesn't drastically alter the state of the game world, but it does give Ethan either a leg up or a slight disadvantage in hunting Shaun down. Is your own child's life worth that of another human being's, no matter how degenerate they may be? Only you know the answer, and you might not like it.

Little Sisters watch out -- BioShock is coming for your blood

"BioShock" from 2007 had some strong first-person shooter gameplay, with its superhuman abilities giving it enough distance from the litany of other FPS games competitors. Those abilities came with a price, however: players needed to secure enough of the magical elixir Adam to ensure they could throw flames, freeze foes, or send bee swarms at enemies in Rapture. The only problem was Adam wasn't always easy to find out in the open... but it was easy to find in the bodies of Rapture's Little Sisters.

Terrible things happened to the denizens of Rapture, but the young girls of the underwater city got the biggest screwjob of them all. Rather than being mutated beyond belief like so many other citizens, the Little Sisters were pumped full of Adam, making them a desirable commodity. Non-player characters would often be found hunting for Little Sisters, but the Big Daddies were never far away to protect them. So, as you found the Little Sisters throughout the game, you could choose to either cure them or steal their life force away. One choice made you more powerful and a creepy monster, not unlike those already roaming the leaking halls of Rapture. The other saved the girls, but left you less capable of defending against those who would see you dead.

It's one thing to give players the choice to kill adults or more mature creatures in order to gain an advantage, but "BioShock" put many players' own morality to the test by having young children at the center of such a decision. Look, we all know how we played–but we won't judge you for doing something different. At least not to your face.

Killing your buddies is a Far Cry from friendship

Once upon a time, the "Far Cry" series was nothing more than another first-person shooter. Sure, it had a jungle setting and introduced some variation on familiar FPS tropes. But it wasn't until "Far Cry 3" arrived that the series took a more personal route that involved moral choices to define the kind of person your character would become.

After getting stranded on a tropical island, game-protagonist Jason must rescue his friends from Vaas, an egomaniacal villain set on controlling Rook Island. If not for the intervention of Vaas's sister Citra and her mystical powers, Jason may well not have been able to foil Vaas and his attempts at ruling the island. However, working with Citra came with a cost of its own, and in the final moments of "Far Cry 3," Jason must choose between saving the lives of his friends or joining Citra to rule Rook Island.

Both choices come at a cost to Jason. Saving the lives of his friends means Jason has to live with everything he did on the island, as one "good" decision does not outweigh all the carnage he caused prior. Killing his friends ultimately also leads to his own death, as Citra murders him soon after, since she only wanted him to provide an heir.

Playing Krogan's heroes (or not) in Mass Effect 3

BioWare's "Mass Effect" franchise offers galactic adventure with plenty of heavy decisions. While some player choices may have resonated a bit more than others (hello romance options), perhaps no choice was more significant to the overall universe than choosing to save the Krogan race or not.

The Krogans were a war-mongering race that populated at an incredible rate. Several other planetary governments decided it would be best if perhaps the Krogans didn't reproduce so quickly, as eventually they'd be populous enough to take over and rule the galaxy if left unchecked. That prompted the creation of the incurable Genophage virus, which just about every non-Krogan alien race in the galaxy saw as a necessary measure. Eventually, "Mass Effect 3" revealed there was indeed a chance the Genophage could be reversed, giving the Krogans an honest chance at survival.

Players could let the Krogans live by curing the virus, but at the expense of losing a trusted friend and ally in Mordin Solus. They could also fake a cure, leaving the Genophage in place, with the Krogans merely believing it had been cured. Neither was an easy choice when weighing all the options, but having the lives of an entire race put in our hands was certainly a decision we'd never want to entertain again.

Lady Boyle and her suitor are Dishonored

Most of the moral plays in the Arkane's "Dishonored" series aren't quite as black and white as so many other games on this list. Often, the decisions you make in the "Dishonored" series are for the good of the kingdom — it just boils down to which version of a decision you want to make. Along the way, there are some small instances where you get to make a seemingly inconsequential decision, such as the optional late-game mission at a masquerade.

The choice of whether or not to kidnap the vile Lady Boyle for a spurned stalker is arguably the creepiest choice you'll ever have to make in a game. Nothing about what the stalker wanted was normal or right. But on the other side of that coin, Lady Boyle was not a very nice person, and giving her a comeuppance of sorts was certainly something many players were willing to do.

Kidnapping someone for the sake of a creep with a crush is inexcusable in the real world, and it's pretty bad in the virtual world, too. Perhaps if Lady Boyle hadn't been such a monster to everyone in her life, players might've felt worse about the decision. But it's still a terrible thing to do to someone regardless of how she treated those around her. Kind of.

Link is a serial burglar

"The Legend of Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom" made players do some pretty awful things, but if we're being honest, Link has been toeing the line of acceptable behavior for a long time. We all know that the hero is a prolific pot-smasher, and someone in Hyrule has to pay for all the damage that he's caused while looking for hidden Rupees. There's also the small matter of the innocent chickens that Link has spent decades tormenting.

Both of those are things that Link does out in the open, but there might be a way to justify some of his behavior. A hero needs supplies, and if it means saving the kingdom, the people of Hyrule are probably more than willing to sacrifice some pots. As for the chickens, maybe they had it coming? Aside from that, there's a much more insidious crime that Link's been committing for almost as long as he's existed.

We're talking, of course, about breaking and entering. There's no building that can keep Link out, and there's no home that the plucky hero isn't willing to barge into. Link is constantly barging into Hyrule's houses. No matter the time of day, he'll throw open a villager's front door and start looking through all of their belongings. It's an invasion of privacy on a truly epic scale. Now, the people of Hyrule never seem to mind that Link has no regard for their personal space, but after nearly four decades of dealing with him, they might just be too exhausted to protest.

Call of Duty makes you complicit in a terrorist act

As a franchise all about warfare, "Call of Duty" offers some inherently terrible decisions for players to make. Sometimes, though, the game doesn't really give you a choice. The franchise's various campaigns have gamers defending America's interests, but even in that context all the killing can occasionally be morally questionable. Meanwhile, the multiplayer modes make a sport out of executing your friends and total strangers. At least everyone's having fun, right?

No matter how many times someone debunks the claim that violent video games lead to real life violence, naysayers are going to have concerns about video games taking things too far. Back in 2009, "Call of Duty: Modern Warfare 2" included a level that seemed almost designed to legitimize those concerns. "No Russian" puts players in control of an undercover CIA agent who has to go along with a terrorist attack on a civilian airport without blowing his cover. Players meet no resistance as they gun down dozens of innocent people on their way to the level's conclusion.

The level leaked ahead of the game's release and sparked instant outrage. Though it does serve a narrative purpose by setting up the game's villain, many felt that including a playable terrorist attack in a game was completely unnecessary. Activision ultimately made the level skippable, but for some that just highlighted how unnecessary the inclusion of "No Russian" really was. Either way, there's no denying that playing through the level is one of the worst things video games have ever pressured us to do.

Halo tempts you into doing bad things for ammo

"Halo" seems like the perfect place to put your questions about morality at ease. As Master Chief, you get to defend all of humanity from massive threats like the Covenant and the Flood. It's possible to charge through every level as a one-man army, blasting enemies to smithereens all while feeling assured that everything you're doing is for the greater good.

Then your battle rifle runs out of ammo. You're crouched behind a boulder on an alien ring world with a legion of Covenant charging toward your location. The marines who came with you are so scared that they're basically useless. They can't aim at anything, and you can't trust them to drive you out of this conflict. If you don't find a way to reload your gun in the next three seconds, a group of Elites are going to tear you and your fellow soldiers limb from limb.

Fortunately, one of your marines has a battle rifle of his very own. Unfortunately, the game hasn't programmed him to immediately lay it down at your feet. The only thing to do is smack him to death with the butt of your gun, peel the ammo off his corpse, and continue fighting your way to humanity's bright future. If you've never killed a fellow marine to get a few more bullets, you're a saint, but if you've never even been tempted, then you haven't played "Halo."

The Last of Us 2 is an animal cruelty simulator

At its heart, Naughty Dog's "The Last of Us" is all about forcing players to do terrible things and deal with the consequences. In the first game, Joel murders countless people on his quest to get Ellie out west. Then, in the game's final act, he betrays the trust of the very person he's come to love and dooms humanity to continue living with the cordyceps infection all at once.

Joel, and by extension anyone playing him, does some truly awful things in the first game. The character lives in a space of total moral ambiguity, and players have to live there with him. Most players probably thought the sequel couldn't pressure them to do anything worse than what they'd already done, but Naughty Dog found a way.

"The Last of Us Part 2" really wants you to kill dogs. During tense stealth segments, enemy dogs can completely ruin your plans and lead a dozen armed killers directly to your location. If you want to be truly safe, your best course of action is to kill however many dogs the enemies bring along before they find you. Of course, if you really want to keep your morals intact, it's possible to play a self-inflicted hard mode and leave all the dogs alive. Even then, the game will eventually force your hand when it comes to one particular dog, ensuring you don't finish "Part 2" without at least a single canine's death haunting your conscience.

Kleptomania is a way of life in Skyrim

Video games have imparted plenty of lessons in the decades we've been playing them, but there's one message in particular that seems to get reinforced over and over again: Stealing is a good thing. Whether explicitly or implicitly, games keep telling players that one of the fastest ways to get rich is to pocket everything in sight and sell it to some hapless shopkeeper down the road.

Bethesda knows that this is one of gaming's most important messages, so it turned the whole concept into a major questline in "Skyrim." Joining the Thieves Guild has been an option in plenty of "Elder Scrolls" games, but the story of the Thieves Guild in the northern nation of Skyrim really is top-notch. Almost anyone who walks into Riften will get the chance to join the guild, and if they do, they'll be rewarded handsomely.

The Thieves Guild in "Skyrim" has some of the richest lore in the series. Players can uncover the Guild's past, reveal some deep disagreements between its members, and eventually rise to lead the Guild themselves. Along the way, they'll also gain access to excellent skill trainers, some of the best quests in the game, and, of course, a plethora of unscrupulous merchants willing to buy stolen goods.

Being a thief has never felt as good as it does in "Skyrim." Just try not to think too much about the folks you're constantly ripping off.

The Walking Dead forces you to make an awful choice

Regardless of the medium, "The Walking Dead" always makes for a grisly story. You don't ever expect a series about flesh-eating zombies and the brutal realities of post-apocalyptic survival to become a feel-good experience, but things feel even darker when you have a say in how the story unfolds. Telltale Games's "The Walking Dead" is one of the best things to come out of the franchise, but the game doesn't take it easy on players' emotions.

Season One introduces players to a young girl named Clementine. Like any other survivor in the series, she's trying to make the best of her current situation, but that's much easier said than done. Clementine was separated from her parents, and she still pretends to have conversations with them to keep her spirits up. Players know that Clementine's parents are dead, however, and the game eventually forces the issue.

What do you do: Tell Clementine the truth so she can begin to heal, or lie to her so that she doesn't have to face the horror quite yet? The morally correct answer is probably to be honest, but when players polled each other, they found out that most people try to spare Clementine the pain. Sometimes people do terrible things for very good reasons, and we can't blame anyone who didn't break the truth to Clementine when they had the chance.

Among Us turns everyone into liars

Some games challenge our morals by design. Everyone agrees that you should tell the truth, especially to people you care about, but that strongly held moral belief goes right out the window the moment you sit down to play "Among Us." If you want to win, you're going to need to stretch, bend, and break the truth.

Right out of the gate, "Among Us" asks at least one person (the Imposter) to do something pretty terrible: kill the crew. That's not really a major concern, though. We've been killing our friends in first-person shooters for years, and everything's turned out fine. What really makes the tasks in "Among Us" so terrible is that they transform the best players into excellent real-world liars.

Dexterity will only take you so far in a game of "Among Us." You definitely need to master various sneaky mechanics, but the real name of the game is deception. Being able to fool your friends into thinking you're innocent, or even more importantly that someone else is guilty, is the only surefire way to come out on top. Most games let players live out a fantasy of going from zero to hero, but "Among Us" is one of the rare titles that, with enough practice, could transform players into master manipulators.

Going off the rails in Disco Elysium

In a way, "Disco Elysium" actually asks players to do something noble. The game puts you in control of a detective and tasks you with solving a murder in a poor seaside neighborhood called Martinaise in the fictional city of Revachol. Despite the morally righteous premise, the player character is the most ill-equipped cop imaginable, and therefore under intense pressure to do things that are downright wrong.

The game begins with the player character waking up from a drinking binge with no memory of his name or anything about the case that he's supposed to be solving. It doesn't take long to get the case on track, but the temptation to slip back into being a bad cop gets stronger. To help solve the case, the player character can do things like try to shoot a corpse off the tree where it's been hanged, or even point their gun at a child to try and get some information.

If firearm misuse isn't enough, the protagonist can turn to drugs and alcohol. The player character's addictions and other bad habits speak to him, attempting to influence his choices throughout the game. Indulging in these bad tendencies might lessen his grip on reality, but also boost some of the stats that he needs to get through the game. Players can choose to take the straight-edge approach to their playthrough, but in many ways it's more effective — and definitely more entertaining — to let those morals go.

Shadow of the Colossus gets dark

In the beginning of the game, "Shadow of the Colossus" dresses itself up like a fairly typical fantasy tale. Players take control of a young man named Wander, who's still grieving the loss of a girl named Mono. Wander has brought Mono's body to a forbidden mystical land, where he hopes a powerful being called Dormin can bring her back to life. Dormin tells Wander that the only way to resurrect Mono is to kill the 16 colossi that march across the land.

Wander wastes no time getting to work, leading into a game that's basically a series of boss battles. Wander leaves Dormin's temple to find a colossus, slays it, and then wakes up back in the temple to start things all over again. Every time Wander slays a colossus, black tendrils of power stab through his body. As the game progresses, Wander's skin pales, black veins start to spread across his body, and he eventually sprouts horns.

Blinded by love, Wander doesn't realize what's happening to him. It turns out that Dormin was a malevolent entity who was sealed away by the otherwise peaceful colossi. By the end of the game, players have helped Wander slay a whole race of creatures and free an ancient evil. It's a dark twist that helped "Shadow of the Colossus" cement itself as one of the best PS2 games of all time, and anyone who has played will never forget the moment they first realized what the game had made them do.

Misbehaving is the point in Bully

Though the game's title would make you think otherwise, the main character in "Bully" is actually a pretty nice guy. Jimmy gets sent to Bullworth Academy against his will, and he already has a reputation for being a troublemaker when he arrives. Going to Bullworth is Jimmy's chance to turn over a new leaf, and he decides to put his energy into navigating the school's various cliques.

Ruling the school means that Jimmy actually has to be somewhat nice to most of the people that he meets. He has to put the Bullies in their place, make sure the Nerds feel safe around him, and beat the Jocks at their own game. If the cliques don't accept Jimmy, his dream falls apart, so there actually isn't as much time for the full-on bullying you might expect.

That doesn't mean Jimmy spends his time at Bullworth being the perfect kid, though. There's plenty of opportunity for misbehaving, and getting into trouble turns out to be the most fun you can have in the game. Jimmy will start a fight with just about anyone. He'll vandalize school property, ride his skateboard where he's not supposed to, and fight back against prefects and the police. "Bully" doesn't ask you to do as many terrible things as Rockstar's other games, but it does give players the opportunity to relive their high school years with a newfound distaste for authority.

Shedding so many tears over Portal

"Portal" is the kind of game that seems like it should be a lighthearted experience. Players get to solve puzzles, explore strange experimental chambers, and laugh at the quirky humor of Aperture Science's testing department. The colors are bright, the jokes are frequent — and then out of nowhere, the game delivers a gut-wrenching moment and forces players to do something almost unforgivable.

Test Chamber 17 introduces players to the Companion Cube, which is just like a regular Aperture Science storage cube, only with a pink heart painted on each side. The Companion Cube is the only friendly presence that players will meet throughout their time with "Portal," and it selflessly allows itself to be used as another tool for solving puzzles. The Companion Cube acts as a laser deflector, a weight, and a stepladder, among other things.

Whatever players need, the Companion Cube is willing to provide. If there's any comfort to be found in the harsh environment of Aperture's labs, it's in the Companion Cube's loving, inert presence. As players come to the end of their time in Test Chamber 17, they're instructed to place their beloved Companion Cube in an incinerator before progressing to the next chamber. The Companion Cube doesn't complain, despite hints that it may have thoughts and feelings of its own.