The Untold Truth Of Fatal Frame

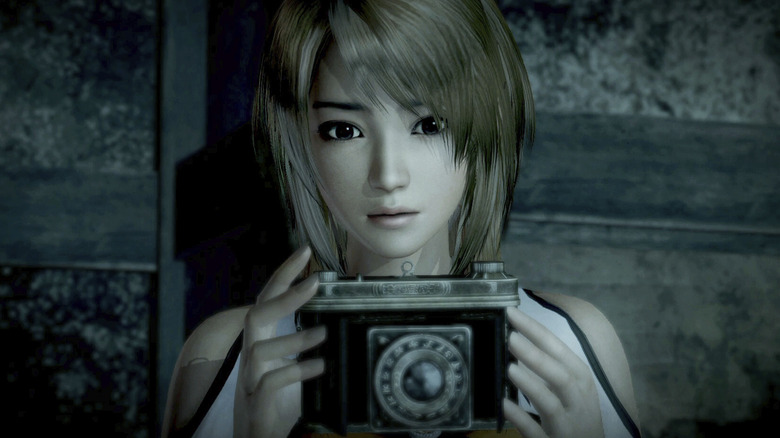

Pop culture says the best way to deal with ghosts is to call either an exorcist or the Ghostbusters, but if you want to handle them yourself, your best bet is a camera and a roll of ghost-capturing film. At least, that's the premise of "Fatal Frame," a beloved horror game franchise that asks players to get up close to ghosts and snap their pictures. For maximum damage, audiences have to wait to see the whites of a ghost's eyes (assuming it has eyes) before they can press the shutter.

While the "Fatal Frame" franchise gives players an opportunity to practice their exorcism and snapshot skills, the games are no mere exercise in flash photography. Every entry is built around a dark story of rituals, gates to hell, and the human drama that gets in the way; it's only fitting that the franchise is also mired in its own real-world secrets and history. Some secrets hide in plain sight and give gamers a scare when they least expect it, while others are inspired by the paranormal experiences of developers that made them question the reliability of reality.

Here are the untold truths of "Fatal Frame" — hiding just out of frame.

What's in a name?

Like other pieces of global media, video games need to adapt when shipped to different regions. A title that makes sense to Japanese audiences might come across as annoyingly verbose to Western gamers. So, changes must be made, but sometimes the meaning behind a title can literally be lost in translation.

As noted by YouTuber Nitro Rad, the "Fatal Frame" franchise's name differs by region. What U.S. gamers know as "Fatal Frame" goes by "Project Zero" in Europe and simply "Zero" in Japan. You might assume that "Fatal Frame" is more appropriate since, in the games, the only thing standing between you and a grisly, ghost-fueled death is a camera. But, that is just tunnel vision talking and ignores the franchise's development history.

In an old PlayStation Blog article, franchise director Makoto Shibata revealed that the game's original working title was "Project Zero," which Europe adopted for its release name. Producer Keisuke Kikuchi also explained that the villains of the game were "beings of nothingness," (translation via FFTranslations), which tied back into the "Zero" of the title perfectly. While the team took inspiration from the "Silent Hill" games, Shibata and Kikuchi focused squarely on what scared Japanese gamers, as well as the fact that Shibata frequently saw things that weren't there. Zombies and monsters might terrify Western gamers, but according to Shibata and Kikuchi, ghosts and dilapidated Japanese houses are what leave Japanese audiences petrified.

You're never safe, not even on the pause menu

Horror games typicaly aren't easy. The constant stress of anxiety-inducing locales — and the occasional jump scare — weighs on gamers. Sooner or later, players need to decompress. However, gamers shouldn't take too long in the "Fatal Frame" games, lest they stumble into new scares by trying to avoid them.

If players leave their controllers alone for five minutes while playing the first three entries, they are treated to surprise scares. Depending on the game, audiences might see bloody handprints smatter the inside of TV screens or a ghastly face stare directly at them. Thankfully, these are only screensavers, not instances of actual haunted game consoles.

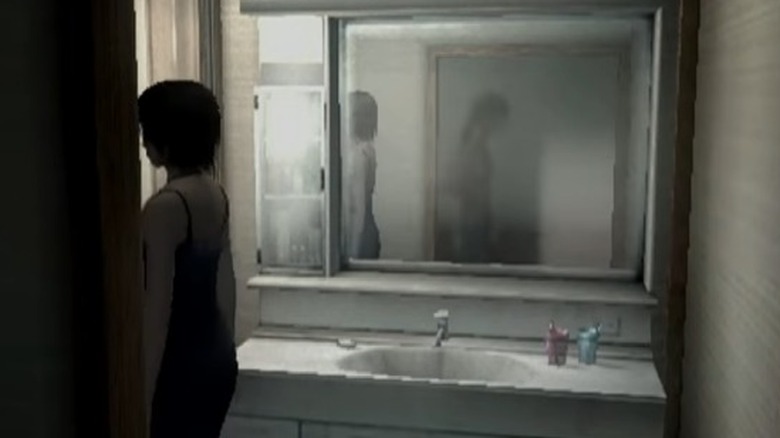

The scares don't end there. "Fatal Frame 3: The Tormented" features a safe home base, partly to further the story, mostly to rip the safety blanket away later. As the game progresses, this urban refuge is steadily invaded by malicious spirits, and several hauntings can go over audiences' heads. Some are obvious, such as ghosts crawling out of mirrors, while others require a keen eye, like a doll with steadily growing hair. Not even the game's menu is safe; if players linger in it too long, they can hear a creepy girl counting to 10.

Video game logic might dictate that certain locations should always be safe, but "Fatal Frame" thrives on shattering expectations.

Inspired by true (personal) events

The first "Fatal Frame" game sported the tagline "Based on a true story" for overseas releases. The veracity of that claim is questionable, but if you change the line to "Inspired by personal events," then it would be closer to reality, since creators tend to write what they know.

While the director of "Fatal Frame," Makoto Shibata, drew from many inspirations, the most influential were his own encounters with the supernatural. According to his online diary (translated by fan site FFTranslations), he used to feel "presences" in the road near his childhood home. Shibata revealed during an interview with Siliconera that these events didn't let up as he grew older. He claims that while visiting the oceanside cliffs of Tojinbo, a spectral presence lifted him into the air as he read graffiti chiseled into the rocks.

Moreover, Shibata can link the influence for certain "Fatal Frame" games to specific events. For example, he claims that the story for "Fatal Frame 2: Crimson Butterfly" came to him in a dream. Also, water is a major theme in "Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water" because Shibata encountered a staggering dry heat during a 2008 visit to Los Angeles. He convinced himself that ghosts cannot appear without at least some airborne moisture, as he said at the time, "I doubt I'd run into any ghosts around here."

Fans might want to take a moment to thank all the spirits Shibata encountered, real or imagined, for inspiring him to make a game franchise about photographing ghosts.

You must be this old to exorcise ghosts

Horror games feature a wide range of heroes. Regardless of backstory, though, they all have one thing in common: They are usually out of their depth when facing abominations against nature and sanity. Since zombies and ghosts can threaten anyone (in fictional settings, at least), you might assume that anyone could also be a survival horror protagonist. "Fatal Frame" localizers seem to disagree.

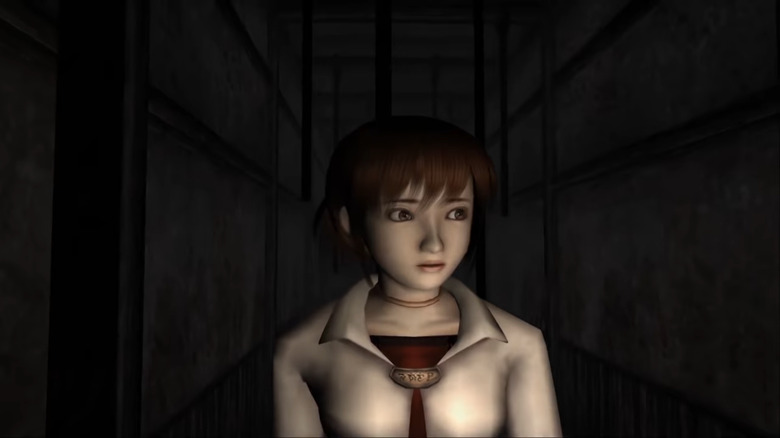

When audiences were initially introduced to the main character of "Fatal Frame," Miku Hinasaki, she braved a mansion full of ghosts to find her older brother. The character seemed particularly vulnerable because you can't exactly punch a ghost in the face. Even if you could, though, Miku was no fighter and little more than a 17-year old high school student, at least in the Japanese version.

Before "Fatal Frame" launched in the United States, the game was localized to fit Western sensibilities. Removing Japanese imagery was out of the question since it was so prevalent (and crucial to the plot), so the localizers instead aged Miku into a college student. Her outfit was changed from a school uniform to more casual clothes, and her face was altered to look older.

This was not the only time Tecmo changed "Fatal Frame" character ages. Originally, the deuteragonists of "Fatal Frame 2," Mio and Mayu Amakura, were 15, but they were aged up to 17 for the Japan-only Wii re-release. Maybe there is a universal age requirement on horror protagonists.

When virtual hauntings invade reality

The subject matter of a video game can heavily affect the mood of the studio making it. After all, if watching scary movies alone can make you feel like ghosts will pop out of a closet at any moment, imagine what working on a scary game would do to an entire team. But, it's only nerves, right? Right?

According to an online diary (translation via FFTranslations), staff members were very uncomfortable working on "Fatal Frame." The more superstitious developers wore charms around their necks while working, and Producer Keisuke Kikuchi wanted to organize a purification ritual to elevate spirits and ward off curses. Makoto Shibata shot that idea down, claiming, "We don't need to do a purification. If we did it wouldn't be scary." Ironically, these paranoid team members might have been on to something.

Many "Fatal Frame" developers reported supernatural encounters in the office and at home. They claimed to hear phantasmal keyboard clacking and ghostly monitor reflections late at night. Eventually, Shibata relented and conducted the purification ritual, but it took until development of "Fatal Frame 3" — and a ghostly encounter in the safety of his own home — to convince him.

Thanks to these hauntings, the "Fatal Frame" team has plenty of stories to tell, as well as some spooky in-game sounds courtesy of recording booth ghosts. No, seriously.

Mission accomplished a little too well

The point of a survival horror game is to scare audiences. Sounds pretty obvious when you say it out loud, but you'd be surprised how many gamers forget that and ask for a rollback on terror.

Many gamers agree that "Fatal Frame" is one of the scariest video games of all time, which is what Makoto Shibata aimed for. However, the game didn't do too well, selling only around 40,000 copies (via Nintendo Everything), so Shibata needed to figure out how to pump up those sales numbers for a sequel. When he started development, his team listened to feedback so they could craft a superior experience and improve their chances of pushing game copies. According to Shibata, a major complaint with "Fatal Frame" was its scares. Many gamers players up halfway because they thought the game was too scary.

Because of this feedback, Shibata trimmed the horror for "Fatal Frame 2: Crimson Butterfly." Instead of taunting players with disturbing phantasms whose deformed bodies reflected their sins in life and means of death, Shibata's team created more generic enemies with less misshapen visages. "Fatal Frame 2" still is a scary game, it's just not as scary in the enemy department.

Despite not reaching the same level of terror as the first game, "Fatal Frame 2" saw better sales numbers. Just goes to show you the frightening power of compromise.

Fatal Frame is not a numbers game

Gamers expect a lot from sequels, including a continuing storyline and a handy numbering guide that tells audiences the playing order of entries. Even though the "Fatal Frame" sequels sport a numbering sequence, they have almost nothing to do with one another. In fact, if it weren't for the ghosts and the spirit-busting Camera Obscura, you'd be hard pressed to realize the games are related. Did the developers drop the ball in that regard? No, it's all by design.

During an interview with Nintendo, Producer Keisuke Kikuchi explained that each "Fatal Frame" game is meant to be an isolated story. This allows audiences to play titles out of order without losing any information; gamers who enter the franchise with "Fatal Frame 3: The Tormented" are as up to date on the series lore as those who have been snapping ghost shoots since the original "Fatal Frame."

You are probably wondering, why Tecmo bothered labeling each game with a numbered title (which implies linked stories) if each entry is its own standalone experience. That's because the numbers were apparently invented for Western audiences, while Japanese "Fatal Frame" titles forgo numbers. For instance, "Fatal Frame 2: Crimson Butterfly" is known as "Zero: Crimson Butterfly" in Japan, while "Fatal Frame 3: The Tormented" is called "Zero: Voice of the Tattoo" in its home country.

Perhaps audiences should consider the "Fatal Frame" franchise less of a sequential game series and more of a collection of interactive ghost stories with common narrative elements.

That's no ghost

The "Fatal Frame" franchise sets itself apart by focusing on one brand of enemy: ghosts. No zombies or demons to be found anywhere, just the twisted remains of spirits caught in a ritual gone wrong. As a result, enemies in each title need to make sense within this context. How did the ghost's living body die? Can their backstory be used to craft a novel enemy? All the ghosts in the games follow this design logic save one.

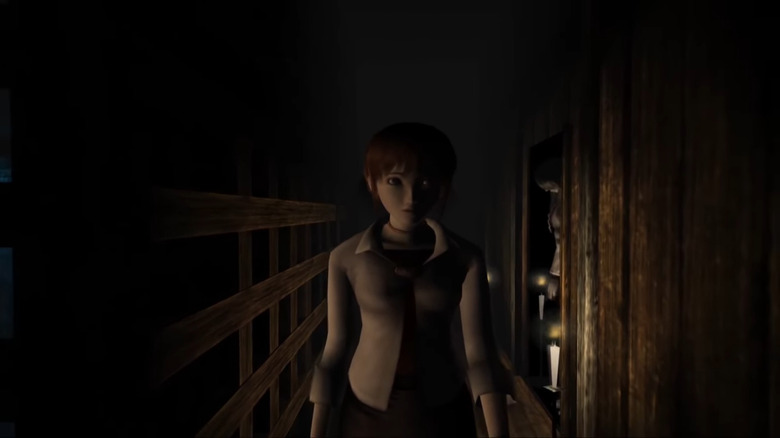

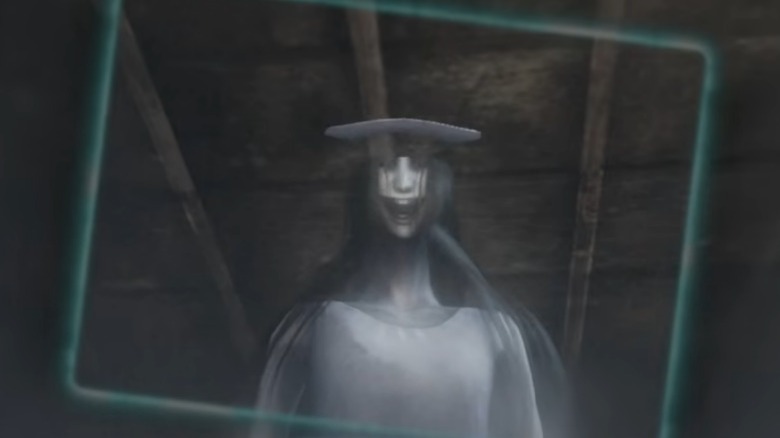

In "Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water," gamers mostly fight humanoid ghosts, but occasionally, fans have noted encounters with a special enemy who stands heads and shoulders above other ghosts — and some trees. Unlike other ghosts, which were clearly human once, you'd be hard-pressed to assume this rare entity was ever human, especially given her towering figure, gangly limbs, and unearthly grin. That's because this ghost is based on the somewhat recent Japanese urban legend of the "Hachishaku-sama," an eight-to-ten-foot woman who kidnaps children. Think Slenderman, but without the dedicated pictures or video games.

This gangly ghost can pop up virtually anywhere in "Maiden of Black Water." Players have found her lurking by the telephone booth, the flooded cemetery, and most commonly invading one of the main characters' houses. These encounters are random, so players can hope for the best — but they should expect the worst.

Ninjas and ghosts don't mix -- or do they?

Horror games have a few tricks to keep players coming back for more. While games such as "Resident Evil" and "Silent Hill" tempt audiences with overpowered weapons that let players breeze through the challenges in a cathartic victory lap, "Fatal Frame" usually offers alternate costumes. Nothing alleviates tension quite like exorcising ghosts while rocking a bikini. However, "Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water" goes one step further and adds ninjas to the mix.

Players who finish "Maiden of Black Water" unlock a bonus mode that, in a surprise twist, stars Ayane of "Dead or Alive" fame. Does this crossover imply a shared universe? All that is known for certain is that Ayane doesn't have a Camera Obscura, so she's helpless against the game's ghosts. Instead, she has to rely on her ninja stealth skills to avoid them.

Yes, in a mega surprise twist, Ayane's bonus mode significantly alters the core gameplay and gives audiences a new experience — sort of. As it turns out, Ayane's adventure sounds suspiciously similar to the original "Fatal Frame" design pitch that didn't feature the camera — players would have had to either avoid ghosts or stun them. While Ayane can't damage ghosts, she has a Spirit Stone Flashlight (an item that premiered in "Fatal Frame: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse") that disorients them in a blaze of spiritual light.

It's not every day gamers can peel back the curtain and see how early design ideas would play out. With ninjas.

Fatal Frame: The Movie

It's no secret that "Fatal Frame" draws heavily from Japanese horror (j-horror) films, and the franchise sometimes wears its inspirations on its sleeves. How fitting would it be if a filmmaker took the idea full circle and turned "Fatal Frame" into its own horror film? Well, someone already did, but in a very roundabout way.

"Gekijōban Zero," literally "Zero: The Movie," is a Japanese movie you probably didn't know existed. The movie isn't an adaptation of the first "Fatal Frame" game or any entry in the franchise. Instead, it is based on a novelization of the first game (bet you didn't know that existed either, did ya?). However even that is a generous description. The movie trades in the source material's haunted mansion for a Catholic girls' school. Also, instead of fighting off hordes of tortured spirits spawned by a failed ritual, the film's protagonist only has to deal with one not-quite malicious ghost created by a curse. Finally, the Camera Obscura is relegated to a few scenes. The protagonist doesn't even get to kill ghosts with it.

While Kotaku praised the film's atmosphere, positive reviews were fairly uncommon. Audiences were divided on the film (via Rotten Tomatoes). Even Kotaku's reviewer disliked the movie's distinct lack of photographic ghostbusting, which is the entire point of the franchise.

Unfortunately, turning video games based on Japanese horror films into their own horror films isn't enough to escape the video game movie curse.

Censorship and Nintendo costumes

When third-party games are ported to Nintendo consoles, or if Nintendo is feeling generous with its first-party titles, developers sometimes insert cheeky extra costumes that reference other Nintendo properties. "Bayonetta," "The Elder Scrolls 5: Skyrim" and "Tekken Tag Tournament 2: Wii U Edition" all received these kinds of costumes pro bono (although some require amiibo figurines). The Nintendo-themed costumes in "Fatal Frame: Maiden of Black Water," however, come at a cost.

Players can unlock special costumes in "Maiden of Black Water," including Zero Suit Samus and Princess Zelda outfits, which characters can wear in subsequent playthroughs. On the surface, this seems like a fun bonus to thank loyal and dedicated players. Audiences didn't see it that way, since the unlockables are exclusive to the American version. Not only that, but wasn't Japanese players fuming; as it turns out, the Nintendo costumes weren't additions, but rather replacements.

As noted by Kotaku, the original Japanese release of "Maiden of Black Water," players can unlock special bikini lingerie that wouldn't look out of place in a Victoria's Secret catalogue. Western releases replaced these with the Nintendo costumes, and when audiences learned this, they accused Nintendo and Tecmo of censorship.

Since "Maiden of Black Water" will soon re-release on modern consoles, one might assume the skimpy unlockables will make a return. However, judging by the recent trailer, these new ports won't feature unlockable lingerie. The official website has confirmed that the Samus and Zelda outfits will remain exclusive to the original Wii U version.

The best laid plans of game developers and localizers

While the "Fatal Frame" franchise was envisioned with Japanese gamers in mind, it found a worldwide audience. After Tecmo ported the first "Fatal Frame" outside of Japan, it only made sense to translate its sequels as well. Unfortunately, one title, "Fatal Frame: Mask of the Lunar Eclipse," is the black sheep of the family for sticking strictly to Japan — but not for lack of trying.

The story of "Mask of the Lunar Eclipse" and its localization is one of dysfunction. As noted by Cubed3, the game received listings in European store websites, and French magazines ran ads that floated a May 2009 release date. Potential American release rumors were even more contradictory. Ex-President of Nintendo of America Reggie Fils-Aime claimed that Nintendo wasn't the game's publisher and had no control over its release, while a Tecmo representative said the exact opposite.

To add further confusion to the dogpile, XSeed Games' Executive Vice President Ken Berry once told a NeoGaf user that "Mask of the Lunar Eclipse" would eventually make its way over to America. While the game never officially released stateside, that doesn't mean English-speaking gamers can't play it.

In 2010, a fan translation team led by Colin Noga unveiled an unofficial English patch for "Mask of the Lunar Eclipse." Moreover, Noga thought three steps ahead and programmed the patch to only work with legitimate copies of the game. Noga's translation project was a labor of love — no, not for the game. According to an interview with Nintendo World Report, Noga did it for his girlfriend, who asked him to make the translation a reality.