The Worst Ideas In Video Game History

In the topsy-turvy world of video games, sometimes risks pay off. Many gamers dismissed motion controls as a simple gimmick, and argued that they wouldn't last. Instead, they opened gaming up to millions of new players, and made the Nintendo Wii Nintendo's best-selling console ever. Converting the Grand Theft Auto franchise from a top-down action game into a 3D adventure title didn't just rejuvenate the series, it created a whole new genre. At first, hardcore fans scoffed at digital distribution systems like Steam, saying that they preferred preferred physical products. Now, digital downloads represent 56% of all video game sales.

But not every idea pans out, and for every one of gaming's major successes, there's at least one catastrophic failure. Here are some of the worst.

The Nintendo Virtual Boy

Let's get the easy one out of the way first: by almost any measure, Nintendo's Virtual Boy was a complete and utter disaster. Even these days, virtual reality systems like the Oculus Rift, the HTC Vive, and Sony's PlayStation VR require beefy, state-of-the-art computers to deliver a compelling (and vomit-free) experience. Trying to achieve the dream of home-based VR with 1995's tech? Practically impossible.

Technical limitations, however, didn't stop Nintendo from trying. Billing the Virtual Boy as the first portable console to display 3D graphics, they marketed the system as a complete game-changer—advertisements implied that, compared to the Virtual Boy, other video game systems were like primitive cavemen. Technically the Virtual Boy did have 3D graphics, and players could pick it up and carry it around, but the system's display was monochromatic and the device was too bulky to truly be considered "portable." In fact, the Virtual Boy's headset was so heavy that many owners complained about neck pain, while others could only play while lying on the ground. The red-and-black graphics and poorly-calibrated 3D effects gave players headaches after only a few minutes, while the virtual reality effects made many users nauseous (a problem that plagues modern-day virtual reality systems as well). Oh, and by all accounts, the games kind of sucked too.

The Virtual Boy only lasted for a year and reportedly shipped fewer than a million copies, making it the second-worst-selling Nintendo console ever. Nintendo blamed Gunpei Yokoi, a longtime employee and "father" of the Nintendo Game Boy, for the Virtual Boy's failure. Yokoi left the company almost immediately after the Virtual Boy's demise. These days, Nintendo executives like Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto dismiss the Virtual Boy as "a fun toy," not a game console, and prefer to discuss the Nintendo 3DS, which successfully integrated 3D graphics with portable gaming—no headset required.

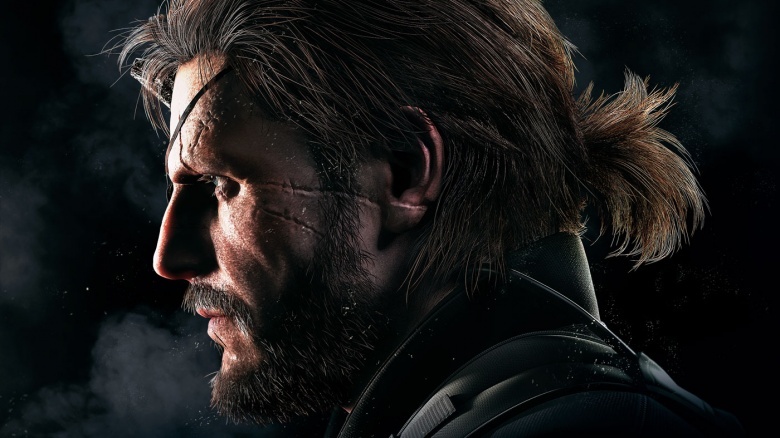

Konami fires Hideo Kojima

If Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto is gaming's Steven Spielberg, then Hideo Kojima is its Stanley Kubrick. Kojima, the man behind Konami's popular Metal Gear franchise, is the closest thing the gaming industry has to a true auteur: none of his games are exactly alike, but each one exemplifies his weird, artful, and whimsical approach to game design. Kojima's games aren't just hits with critics, either—the Metal Gear Solid series alone has sold over 49 million copies.

And yet, for some reason, Konami decided to sever ties with Kojima just as Metal Gear Solid 5, Kojima's final entry in the Metal Gear saga, prepped for release. For the last six months in Metal Gear Solid 5's development, Konami kept Kojima in a locked room, unable to communicate with the rest of his team. The company removed Kojima's name from Metal Gear Solid 5's marketing materials and restricted Internet access at Kojima Productions, which it renamed Konami Los Angeles Studios. In December 2015, two months after Metal Gear Solid 5 released in a clearly unfinished state, Kojima left the company.

That was bad news for Metal Gear buffs, but it's even worse for Silent Hill fans. In 2014, Kojima and Konami released P.T., a short "playable trailer" (hence the name) for Kojima's upcoming Silent Hill reboot, Silent Hills. Players downloaded P.T. more than a million times, while Capcom's Resident Evil 7 takes more than a few cues from P.T.'s short-but-memorable gameplay. Unfortunately, Konami cancelled Silent Hills alongside Kojima's contract. Hideo Kojima's next game, Death Stranding, will reunite Kojima with his Silent Hills collaborators Guillermo del Toro and Norman Reedus, but as far as Silent Hills is concerned, fans are stuck imagining what could've been.

The Apple Pippin

Remember when Apple released its own video game console? No? Yeah, there's a reason for that. In 1996, the company launched the Pippin (or as marketing materials called it, the PiPP!N), a CD-based multimedia machine designed to play videos, music, and games. The Pippin was also the first gaming console to include a built-in modem, which owners could use to access the quickly growing internet.

Apple didn't manufacture the Pippin itself. Instead, it licensed the design, which was based on Apple's Macintosh computers, to other manufacturers. Bandai, Katz Media, and Mitsubishi all signed up to bring the Pippin to market, although only the former two actually ended up producing devices. Bandai launched its version of the console, the Pippin @WORLD, in early 1996 (March for Japan, and June for the USA) for a cool $600.

Apple refused to do any marketing for the device, leaving promotion in the hands of its licensees—Bandai reportedly spent $93 million alone marketing the @WORLD. It didn't pay off. Not only was the Pippin much, much more expensive than its competitors the Sony PlayStation and the Sega Saturn, but Bandai was the only major company creating software for the system, meaning that the Pippin had very few games. Bandai reportedly produced 42,000 @WORLD systems but only sold about 12,000 units, leading to a huge loss.

Thankfully, the misery didn't last long: when Steve Jobs returned to lead Apple in 1997, he killed Apple's "clone" program, which let outside manufacturers produce Mac computers. This included the Pippin, which was based on Macintosh architecture, thereby dooming the console to a quick and unceremonious death.

Jamie Kennedy hosts Activision's E3 press conference

The Electronic Entertainment Expo isn't just a trade show. It's also one of, if not the, biggest event in the video game industry. Part press conference, part pep rally, and almost always crazy, E3 is the one time of year when video game publishers pull out all the stops to dazzle fans, media, and (most importantly) retailers with their upcoming video games.

Sometimes, companies recruit celebrities to help give their annual E3 presentations an air of glitz and glamour. In 2015, Electronic Arts brought out Pelé—the best soccer player of all time—to promote FIFA 2015. In 2009, Paul McCartney and Ringo Starr hit the stage to promote The Beatles: Rock Band. Years before he decided to become the leader of the free world, Donald Trump appeared at E3 to hawk the Xbox.

But not every celebrity that appears at E3 is exactly A-list. In 2007, Activision recruited Scream star Jamie Kennedy to host the company's annual press conference. It was an unmitigated disaster. Kennedy showed up seemingly inebriated, and spent the entire presentation making fun of players, developers, and the press—y'know, the people the event is designed for. Hacky jokes like, "I see so many virgins out there, Richard Branson must be running this event" quickly alienated the audience, and almost ten years later, Kennedy is still defending himself on Twitter against legions of angry fans.

The THQ uDraw

The problem with THQ's uDraw tablet wasn't the device itself—by all accounts, the peripheral works pretty well. The problem is that practically nobody bought it, bringing a 30-year-old company to its knees.

The uDraw was originally released as an add-on for the Nintendo Wii, which provided users with a 4x6 screen that could be drawn on with a stylus, in addition to being used as an alternative game controller. Critics tended to like the device, which paired with kid-friendly drawing games like Pictionary, uDraw, and SpongeBob SquigglePants.

Unfortunately, while the Wii version of the uDraw performed decently, the PlayStation 3 and Xbox 360 editions tanked at the marketplace, leaving THQ stuck with roughly 1.4 million units—a shortfall that cost the company $100 million. In 2012, THQ president Jason Rubin—who joined the company after the uDraw debacle—cited "the incredible losses attached to uDraw" as one of the main reasons for THQ's bankruptcy, which was ultimately resolved when it was dismantled and its former properties were auctioned off.

Sony launches the PlayStation 3 at $600

In 1995, at the very first Electronic Entertainment Expo, Sony stole the show with what's come to be known as "The Price Heard around the World." Shortly before Sony's press conference, SEGA rocked the gaming community: not only had its latest console, the SEGA Saturn, had shipped to stores the night before, but it would cost $399, far more than anyone expected. In response, Sony Computer Entertainment America president Steve Race, the man in charge of bringing the PlayStation to the USA, took the stage for a brief announcement: "$299."

Race's three-word speech is considered one of the greatest moments in E3 history. Unfortunately for Sony, it also set fans' expectations sky-high. In 2006, Sony returned to E3 to promote the upcoming PlayStation 3. The demonstration didn't go well—the onstage demos were underwhelming and the Dualshock 3 controller's motion-based controls didn't look like they worked at all—but Sony saved the worst for last. Right before the press conference ended, Sony CEO Kaz Harai took the stage and announced the PlayStation 3's price: $599. The audience gasped.

Thanks to its high price point, Gabe Newell, the president of Valve, called the PlayStation 3 "a disaster." Activision Blizzard CEO Bobby Kotick threatened to drop PlayStation 3 support if Sony didn't lower the price. Ultimately it dropped and sales picked up, but it took awhile—as late as 2013, the PlayStation 3 trailed the Xbox 360 in market share, despite the latter's dismal sales in Japan.

Nintendo betrays Sony

Do you love your PlayStation? Oddly, you have Nintendo to thank. Before they were rivals, Nintendo and Sony were actually partners—and if Nintendo hadn't stabbed Sony in the back, the current gaming landscape would look completely different.

In 1988, Nintendo and Sony joined forces to create a CD-based Super Nintendo Entertainment System that would play both SNES games and CD-ROM exclusives Sony would control. Sony revealed the fruits of that team-up, the Nintendo Play Station, at 1991's Consumer Electronics Show. The Nintendo Play Station represented a big step forward for both companies: with the peripheral, Nintendo seemed poised to embrace high-tech multimedia formats, while the Play Station would mark Sony's first-ever foray into the lucrative video game market.

But Sony's triumph was short-lived. The day after Sony's presentation, Nintendo of America chairman Howard Lincoln announced that Nintendo would be abandoning Sony and forming a partnership with Phillips, who had launched a CD-based multimedia machine, the CD-I, earlier that year. The sudden reversal didn't just ruin Nintendo's reputation among the Japanese business community, it also outraged Sony executives, who decided to get revenge by producing their own console.

The Nintendo-free Sony PlayStation arrived on December 3, 1994, and Sony has been a thorn in Nintendo's side ever since. The original PlayStation outsold the Nintendo's cartridge-based Nintendo 64 3-to-1, while Sony's latest console, the PlayStation 4, has a 32 million unit lead on Nintendo's recently discontinued Wii U.

The Nokia N-Gage

It seems quaint now, but once upon a time people used mobile phones for phone calls, not playing games. In 2002, when most gamers had to stuff Game Boy Advance systems into their pockets in order to play on the go, Nokia tried combining a phone, a game system, and a media player into one device. The result, the Nokia N-Gage, was incredibly forward thinking—or it would've been, if it had worked at all.

While the N-Gage was a good idea, it didn't work very well as either a gaming system or a basic communications device. The N-Gage's buttons, which resembled a traditional phone keypad, were an awkward fit for video games. Meanwhile, thanks to the N-Gage's bizarre design—critics compared the device to a taco on more than one occasion—it had to be held perpendicular to the user's ear when used as a phone. In order to change games or use the machine as an MP3 player, owners needed to turn the device off and take it apart, and the whole thing cost $300—three times as much as the Game Boy Advance.

The N-Gage tanked pretty much immediately (retailers slashed the price by $100 just a few weeks after released). A 2004 redesign called the N-Gage QD improved the device, but the brand was already damaged—while Nokia says that it shipped over two million devices, third party trackers estimated that only about 5,000 N-Gage units actually sold in the United States. In 2008, Nokia revived the brand as an online gaming service for Nokia phones, but the system, known as N-Gage 2.0, closed up shop less than two years later.

Nintendo uses cartridges on the Nintendo 64

While most mid-'90s consoles—the PlayStation, the Sega Saturn, the Atari Jaguar, and others—used CD-ROMs to store their games, Nintendo spent the fifth console generation stuck in the past. Instead of optical discs, which can store vast amounts of data, Nintendo decided that its first 3D-capable system, the Nintendo 64, would retain the cartridge-based design that worked so well for the Nintendo and Super Nintendo Entertainment Systems.

Nintendo of America chairman Howard Lincoln said, "cartridges offer faster access time and more speed of movement and characters than CDs," providing players with a better overall gaming experience than optical discs. Developers disagreed. Third parties like Squaresoft and Enix jumped ship, moving their in-progress titles to Sony's rival PlayStation. "As a result of using a lot of motion data + CG effects and in still images," Squaresoft's Hironobu Sakaguchi explained, "[Final Fantasy 7] turned out to be a mega capacity game, and therefore we had to choose CD-ROM as our media." Other companies, like Konami, continued producing games for Nintendo, but scaled back their output due in part to the challenges involved with making cartridge-based titles.

Nintendo never quite recovered. While Nintendo's portable systems, the Game Boy Advance, the DS, and the 3DS all enjoyed healthy third-party support, its home consoles (the best-selling Wii aside) remain largely first-party affairs.

John Romero's about to make you his… what?

You may not recognize John Romero's name, but you certainly know his work. As a developer at id Software, Romero (along with co-worker John Carmack) is responsible for games like Wolfenstein 3D, DOOM, and Quake. Basically, while Romero didn't necessarily invent the first-person shooter, he carries more than his fair share of responsibility for the genre's popularity (reportedly, Romero is responsible for coming up with the term "Deathmatch" to describe player-versus-player contests).

After Romero left id, he co-founded Ion Storm, where he started work on his next project, a shooter named Daikatana. Understandably, Ion Storm used Romero's name to promote the in-production project. Less understandably, the company decided to antagonize its audience, taking out ads in gaming magazines that proclaimed, "John Romero's about to make you his bitch."

"I mean, there's the whole culture of smack talk that goes with games and especially the FPSs, and that was something I was known for," Romero said later, but admitted that the Daikatana's ad campaign was needlessly hostile. "I felt I had a great relationship with the gamer and the game development community and that ad changed everything... I regret it."

Maybe the ad would've been justified if Daikatana had been any good, but it wasn't. The game's budget swelled thanks to numerous delays and Romero's rock star lifestyle, and by the time Daikatana finally debuted in 2000, its tech was noticeably dated. Thanks to the aggressive ad campaign, Daikatana faced expectations that it couldn't match, and while the reviews weren't terrible, they weren't great either. Ion Storm's Dallas office closed and Romero moved to Midway, ultimately putting first-person shooters in the rearview mirror and forging a long-lasting career as a developer of mobile titles.