The Truth About The Video Game Crash Of 1983

Back in 1983, the course of retail history was changed forever when an industry-wide recession hit the North American video game industry, which was then led by Atari, causing the bankruptcies of some large players and putting the entire future of the budding industry into doubt.

"Video games were dead, dead, dead," said Wired in a 2010 retrospective on the Nintendo Entertainment System, which can be credited with pretty much saving the industry when it was released in 1985. Ultimately, Nintendo's smartly designed system (it was meant to fool retailers as an "electronic toy") would become, as Wired said, "the most influential videogame platform of all time" because it managed to turn everything around.

But why did the video game industry suffer such a huge setback, given how much money and time is spent making and consuming games today? An analysis from Newzoo speculated in May that revenue from the gaming industry would top $159 billion in 2020, with projections surpassing $200 billion by 2023. Gaming is big business today, and it's hard to imagine how close game production was to being choked off altogether in its infancy. Here's the truth about the video game crash of 1983.

There wasn't just one factor — stop blaming E.T.!

Legend has it that the entire $11.8 billion (at its peak) video game industry was brought down by one bad (yet cult-classic) video game after five years of boom times, resulting in the combined assets of console purveyors totaling just $100 million. Yikes. But, while E.T. the Extraterrestrial makes for a high-profile scapegoat, it wasn't really his fault that the whole industry came crashing down on his square-shaped head. Many factors led to the crash.

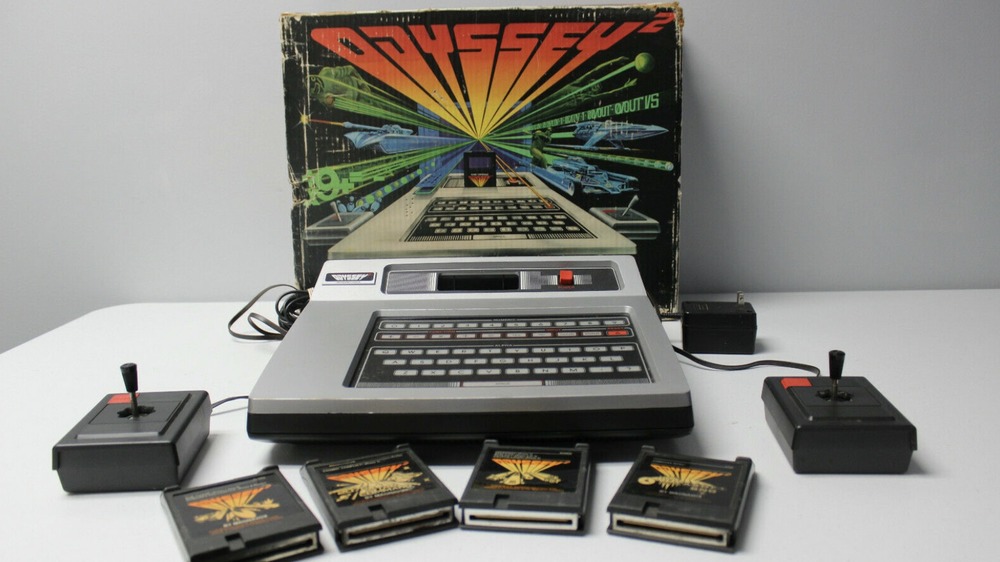

With a young industry still trying to figure out what works best, execs made some colossal mistakes. For example, the market was glutted with consoles, including multiple Atari products, ColecoVision, Intellivision, Milton Bradley's Vectrex, and the Magnavox Odyssey. Meanwhile, PCs were becoming serious competition. There was even insider trading involved. At the time, plenty of optimism (and hubris) permeated video game business units, and inexperienced, newly formed third-party publishers flooded the market with low-quality games. In fact, 12 million copies of the less-than-perfect Pac-Man were produced for the Atari 2600 console, even though only ten million people owned the system. All this led to a loss of consumer confidence and a crash for the ages.

Its effects were wide-ranging — and not all bad

Atari never recovered, and its last attempt at a console system failed in the mid-'90s. Coleco left the industry to focus on its toy lines. Magnavox, maker of the very first video game console, saw its Odyssey 2 suffer from the fallout and then only released the Odyssey 3 in Europe. Retailers started becoming wary of anything connected with the industry.

But it wasn't all bad. In fact, some say the word "crash" is too hyperbolic to apply to a change which negatively affected industry players but was actually good for consumers. PC gaming thrived as companies like Activision started to diversify, making games for computers instead. Also, plenty of people could now pick games up at bargain-basement prices, leading to many younger adults discovering gaming.

The lessons of the event caused console developers to keep a closer rein on what was published for their systems (via safeguards such as Nintendo's lockout chip) and to focus on better development and testing. Additionally, the crash allowed Japan, led by Sega and Nintendo, to take over dominance of the industry. Basically, it affected the way the industry looks today — for better or worse.