Rules Every Resident Evil Game Has To Follow

When you hear the words "Resident Evil," you probably think about zombies, green herbs, convoluted door locks, and magical hammerspace storage chests. These features are synonymous with the franchise, but they actually don't follow immutable rules. Resident Evil might have started with typical shambling cadavers, but the series has branched out to brain parasites and werewolves. And we cannot forget the time Resident Evil replaced storage boxes with a wandering one-man black market.

Even though Resident Evil's key features aren't set in stone, the developers still follow explicit rules while crafting each title — or try to, at least. The timeless enemies are occasionally swapped out for new models to keep players on their toes, but Resident Evil is defined by a specific, steadfast design philosophy that (usually) permeates every game.

For those who may be curious, here are the rules Resident Evil developers try to follow for every entry.

Not just any old horror will do in Resident Evil

Resident Evil is a horror franchise, but horror is a vague concept. Some horror games craft unnerving setpieces that are no more dangerous than haunted house rides, while others rely on jump scares. And some horror games blindside players by nuking the fourth wall. Resident Evil games set themselves apart from the rest by building horror that hits close to home.

According to Resident Evil 7 director Kōshi Nakanishi, personal horror is the pinnacle of Resident Evil. If a player can picture themselves in a game's scenario, their fear multiplies. Few people can gallivant across the globe and dismantle international zombie conspiracies, but anyone can wander into dilapidated houses infested with insane, superhuman hillbillies and fungus zombies.

Nakashini believes fear comes from the imagination. A good Resident Evil game captures a player's imagination and twists it against them. Whether or not zombies lurk around a corner, players should always imagine something evil lies in ambush. This design stems from ex-Capcom director and producer Shinji Mikami, who stated Resident Evil must make players "simultaneously feel fear and enjoy playing the game."

Fear and pleasure are two sides of the same coin in horror. One without the other is like vinegar-flavored potato chips without salt to balance out the taste.

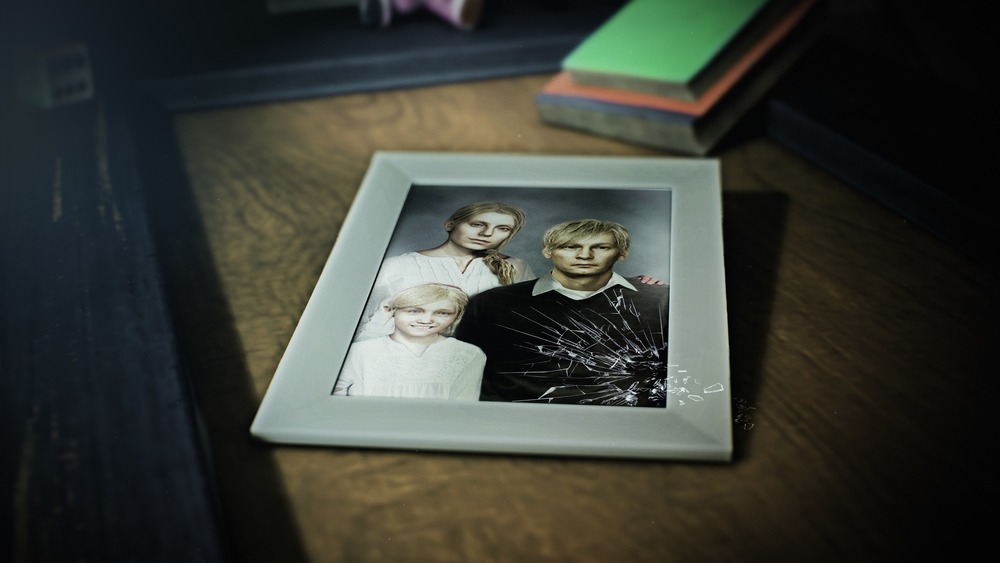

Build up the world — and scares — with diaries

You can fit only so much story into a game before the narrative becomes bloated and unwieldy. To help flesh out a game world, many titles include notes and diary entries that provide windows into daily lives before the zombies rose to power. These notes aren't always considered essential, but Resident Evil's developers think otherwise.

Resident Evil games use cutscenes to provide important plot points and character motivation, but Kōshi Nakashini believes cutscenes are only half the equation. A cutscene might reveal Albert Wesker's true motives, but diary entries provide crucial information about the game world's backstory and lore.

As Nakashini told Forbes, "There are cutscenes, but all of the notes and diary entries hidden within the mansion really helped to build an ominous narrative in the background." Resident Evil isn't just about the events happening onscreen but also the ones that led up to them. A zombie outbreak is old hat, but a newspaper scrap that mentions water toxicity gets players thinking and implies infected drinking water caused the zombies.

Resident Evil isn't a franchise where things just happen. Each game needs to provide breadcrumbs, and players fill in the gaps along the way with collectible diary entries. It certainly beats an exposition dump.

You can't go to easy on the player

Game difficulty is a hot topic. Some people argue that all games need an easy mode, while others claim easy modes defeat the purpose of certain games. Where does the Resident Evil franchise stand in this discussion? Despite the series' use of difficulty modes, RE sits in the "the game is supposed to be challenging" corner.

System planner of Resident Evil and director of Resident Evil 0, Koji Oda, feels Resident Evil needs to work against the player. The franchise is about delivering a horror experience, and RE games have to be tense as possible to maximize the horror.

Normally, you know how much health a character has, but Oda is adamant that intentionally hiding the protagonist's health adds tension. In the game, healing items are in short supply, so you never know if you can take another hit or if you need to heal immediately. Furthermore, the save system also uses similarly limited items, so you can't save every five minutes — the fear of wasting saves prematurely adds a new layer of stress.

Even on easier difficulties, Resident Evil shouldn't hold the player's hand. If the game is a cakewalk, then all the horror is sucked out of the experience. Horror is the entire point of Resident Evil.

Resident Evil is more than a name -- it's a brand

What's in a name? A lot, since a video game's name can impact its marketability and recognizability. Super Mario Bros. probably wouldn't be half as popular if it were called Jumping Italian Plumbers! Likewise, the Resident Evil franchise relies on its name to attract gamers, even though it isn't called Resident Evil the world over.

In case you didn't know, Resident Evil is known as Biohazard in Japan, and Yoshiaki Hirabayashi, who has worn many hats throughout the franchise's life, is of two minds about its name. While he thinks Biohazard is better fitting, he acknowledges the power and necessity behind the name Resident Evil. While some franchise entries don't take place in houses (i.e., where the "resident" in Resident Evil originated), Hirabayashi believes virtually every gamer can pinpoint key features of upcoming RE games with near prophetic accuracy just by hearing the title. Therefore the Resident Evil name holds power and is crucial to the franchise.

If you want further proof, examine Resident Evil 7. In the U.S., its full title is Resident Evil 7: Biohazard, but in Japan, it is called Biohazard 7: Resident Evil. That is a first for the franchise in Japan and demonstrates Hirabayashi's point.

Perfectly balanced, as all things should be

How much realism is too much in video games? How much fantasy is over the top? Many game developers scratch their heads while balancing the two. Devs need to weigh realism against fantasy, as well as the plot, to ensure players can maintain suspension of disbelief. However, the proper realism-to-fantasy ratio was cracked a long time ago for the Resident Evil franchise.

When Yoshiaki Hirabayashi was a designer for the Resident Evil franchise, he worked closely with Shinji Mikami. According to Hirabayashi, Mikami claimed the key to Resident Evil's world is balancing the "real and unreal." Despite all the zombies and evil viruses, the game world still needs to provide a "verisimilitude of a realistic world," which explains why the t-virus can gift some people with combustible blood but can't give them powers like telekinesis. Granted, Hirabayashi admitted some RE games lean more towards the fantastic than the real and vice versa, but he tries to stay true to Mikami's guiding words.

If games are like meals, then the real and unreal are the spices. You can use a bit more realism than fantasy to give a Resident Evil game a specific flavor, but too much and the end result becomes inedible.

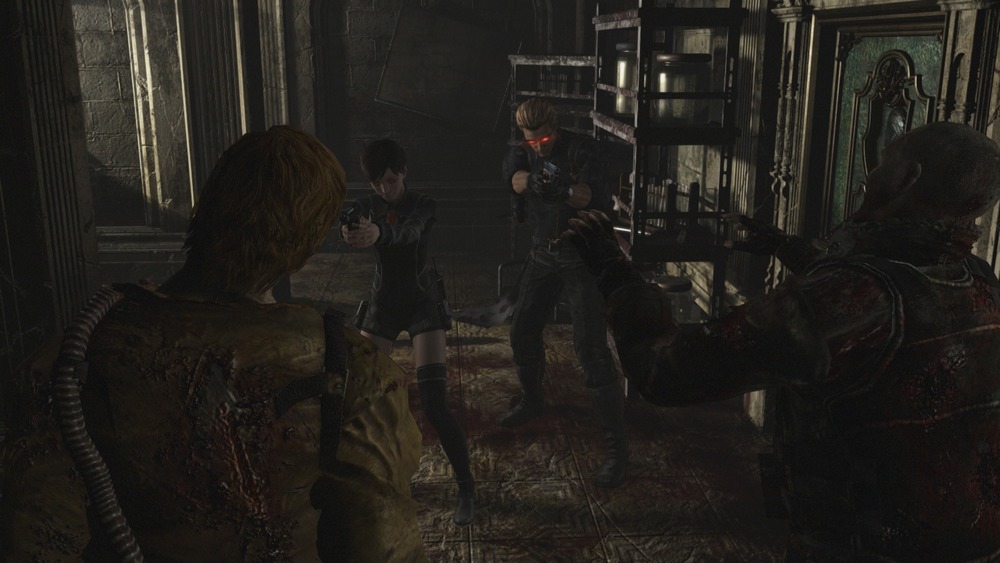

For every action, there is an equal and opposite reaction

Survival horror games have an ebb and flow. You're hopelessly outnumbered, fighting for your life against creatures that crawl towards you even after you've surgically severed their spines with bullets. However, you always have a shot at survival, or at least you're supposed to as far as Resident Evil design is concerned.

According to Resident Evil 6's director Eiichiro Sasaki, each RE monster is a game of actions and reactions. You encounter a zombie and shoot its head. But, if you are pinned by a monster who can only be damaged in specific locations, you aim for its glowing, pulsating weak spots. Sasaki despises no-win scenarios and believes every Resident Evil fight should be winnable. He thinks that even if you are forced into situations where you have to adopt unusual, uncomfortable tactics (for example, tricking blind Garradores into sticking their claws into walls so you can shoot their unprotected, parasite-ridden spines), victory should always be possible.

Unlike franchises like Silent Hill, which occasionally use invincible enemies, there's no such thing as an immortal monster in Resident Evil. Even Regeneradors have an Achilles heel the size of Wesker's ego, even if you can only see it in infrared.

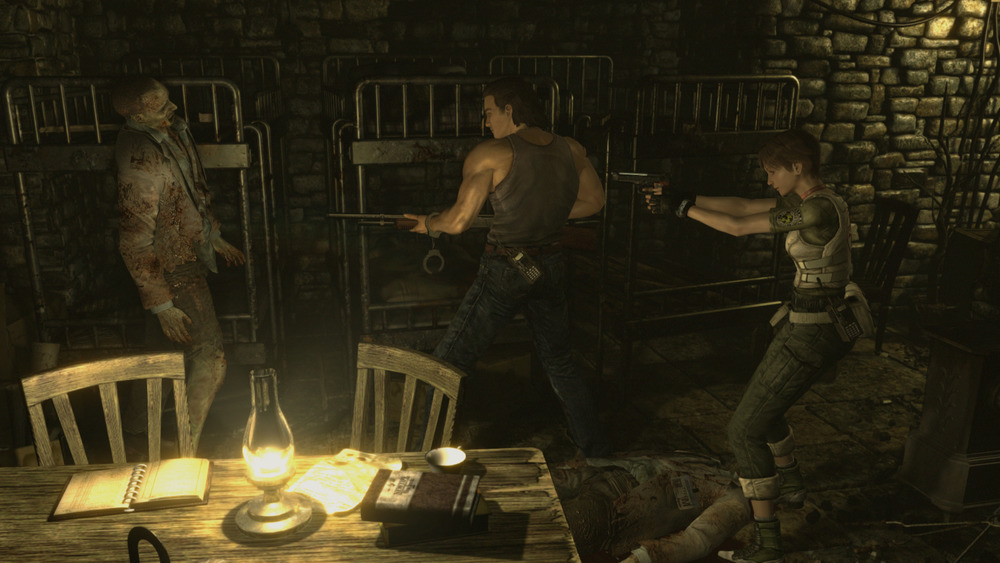

You can't make players feel comfortable around zombies

Survival horror games usually follow a specific combat design. Ranged weapons are really powerful, especially against living things (as well as undead things), but ammo is in short supply. Guns should be saved for emergencies when rusty pipes and fire axes don't cut it. Resident Evil defies this design philosophy, and for good reason.

Even though Resident Evil games sometimes sneak in melee weapons, they are usually weak. Your best chance of survival is either a gun or a quick retreat, and that's an intentional design choice. Naboru Sugimura, who helped write Resident Evil 2 (as well numerous Lupin the 3rd and Super Sentai episodes), has stated melee weapons diminish the franchise's scares and give players a reason to approach deadly monsters. According to Sugimura, Resident Evil's enemies are supposed to emphasize the belief that the further you are from a zombie, the safer you are.

While some RE games provide more melee options than others, Resident Evil games more often than not hold true to Sugimura's claim that proximity equals danger. How else would you explain Dr. Salvador and his insta-decap chainsaw?

Always expect censorship

Did you know Resident Evil isn't kid-friendly? Every RE title is slapped with the "M for Mature" rating to ensure gamers younger than 18 don't play them, but not all ratings boards are created equal. Different boards and their respective countries have their own standards and hangups, which doesn't bode well for franchises like Resident Evil.

Resident Evil 7's director Kōshi Nakanishi claimed censorship is a constant concern during development. Dev teams have specific visions, which are always tempered by ratings boards. A level of violence acceptable in the American market (accounting for an M-rating) won't fly in Japan. Developers have to second guess their work and ask if a particular scene will prove problematic in certain countries. According to Nakanishi, RE devs have to censor themselves and prepare milder alternatives to placate the Japanese ratings board, even though they can go full slasher movie for the American ratings board.

The RE franchise is full of examples where "intense" scenes in American releases are toned down for Japanese audiences. For example, Dr. Salvador's chainsaw doesn't decapitate Leon in the Japanese version of Resident Evil 4. Moreover, zombies can be reduced to giblets in every version of Resident Evil 2 Remake except the Japanese one.

Resident Evil is doing the same thing over again but with different results

When people purchase video games, game length can be a deciding factor. Some gamers would rather purchase titles that provide 50+ hours of entertainment over games that last four hours. Resident Evil campaigns tend to be on the shorter side of the game length spectrum, but only if you play them once. If you don't load up RE games for a second or third go around, you're not playing them as the developers intended.

Resident Evil games include extra modes like The Tofu Survivor, and according to Shinji Mikami, mode was added to Resident Evil 2 to keep players coming back for more. Most entries in the franchise follow Mikami's vision and give players rewards for multiple playthroughs. For instance, the Resident Evil HD Remake unlocks the Real Survival difficulty mode after players complete the game twice. Meanwhile, Resident Evil 4 unveils Ada Wong-centric missions after players finish the main game.

Even when a game is light on extra modes, they offer unlockable weapons. These weapons of zombie devastation trivialize the horror and are played for laughs, but who says a horror game can't have a sense of humor? If Resident Evil 4 is a marathon, a playthrough with the Chicago Typewriter is a victory lap.

You will always need to manage items

When you think about the Resident Evil franchise, your mind probably leaps to the core gameplay loop of surviving a zombie outbreak in close quarters with limited resources. This raises the question of why resources are limited, and the answer comes in two parts. First, you can't find many bullets and herbs, and more importantly, you can only carry so much before your pockets rip.

Ask virtually any Resident Evil developer, and they will explain how item management is a vital part of the franchise. With few exceptions, players can only hold what fits on a small inventory grid window, and not even the Tetris world champion can cram everything into it. Do you fill your pockets with handfuls of ammo for different weapons, or do you horde bullets for one weapon and leave the rest behind? What is the proper ammunition-to-healing item ratio? What do you store when you have to lug around puzzle items? The answers vary from person to person, which is the entire point.

Item management has been with the Resident Evil series since the beginning, and it will likely stick with the franchise until the very end.

Bridging communities and markets through horror

Whenever someone researches Resident Evil 6, they usually find criticism of the game. Apparently, RE6 tried to please everyone and suffered as a result. Well, you might be surprised that "trying to please everyone" isn't too far from the RE franchise's core tenet.

RE6 director Eiichiro Sasaki claimed that Resident Evil games should strive for "universality" and "global appeal," that RE developers should channel common ground between different cultures into an entertaining game. Of course, the irony of discovering universality is nobody agrees on how to do it. According to Sasaki, the RE6 team experimented with ideas such as placing black bars on cutscenes to make the game look more like a movie, as well as filling the script with f-bombs. These ideas didn't work. However, Shinji Mikami discovered the secret to Resident Evil's universality early in the franchise's life.

Mikami believes the secret of universal appeal lies in channeling RE's core theme of terror, because — as he put it — "terror can be perceived by everyone." According to Mikami, this focus on easily recognizable horror helped the franchise's popularity. The games tapped into a well of terror hiding in each player, and the rest was history.

The camera always points towards immersion

Resident Evil's camera defines its presentation. Originally, the franchise used fixed camera angles that imitated slasher horror movie cinematography, but as the times changed, so did technology and camera angles. Developers didn't need to change the game camera, but they did for the sake of immersion.

Resident Evil 2 Remake is a mostly faithful recreation of the original title, and one of the remakes biggest changes is its over-the-shoulder perspective. According to Brand Manager Mike Lunn and Yoshiaki Hirabayashi, this camera creates a more immersive experience. Hirabayashi claimed that witnessing a struggle between survivor and zombie up close is more intense than viewing it from afar. However, this isn't the only way the RE franchise has chased immersion.

While over-the-shoulder perspectives became the norm, Resident Evil 7 uses a first-person, found footage-esque camera. This decision seemingly defies the proverb, "If it ain't broke, don't fix it," but the dev team wanted to immerse players further than any third-person camera could. Producer Tsuyoshi Kanda and Senior Manager Peter Fabiano agree that first-person is more immersive than third-person, and producer Masachika Kawata stated the team implemented VR functionality to, you guessed it, increase RE7's immersion.

At the rate things are going, Resident Evil might turn into a first-person franchise for the sake of immersion.