What Really Went Wrong At Telltale

On September 21, 2018, 250 Telltale employees were informed that they no longer had jobs, they would not be paid any sort of severance, and they had 30 minutes to leave the building. All their projects, save for a contractually obligated port of Minecraft: Story Mode to Netflix, were canceled. The in-progress final season of The Walking Dead would be, essentially, in limbo, pulled from digital storefronts.

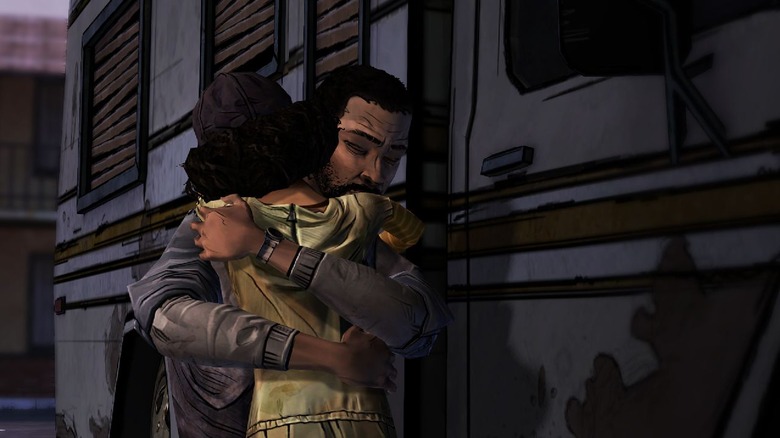

It was an ignominious end to one of the most respected narrative-focused developers on the planet, but, sadly, it also wasn't a surprise. The writing had been on the wall for some time; in a way, it stretches all the way back to the success of The Walking Dead: Season 1. In the wake of this shocking turn of events, it's worth diving into exactly how the mighty Telltale fell, and all the mistakes that led to its demise.

Doing too much in too little time

Telltale has been a fairly prolific company since its inception in 2005, but the scale of its IP weren't always as high-profile as, say, Batman or Game of Thrones. The biggest license Telltale had starting out was to make a couple of CSI games for Ubisoft. For the most part, Telltale's CV up until they landed Back To The Future consisted mostly of LucasArts hand-me-down series like Sam & Max and Monkey Island.

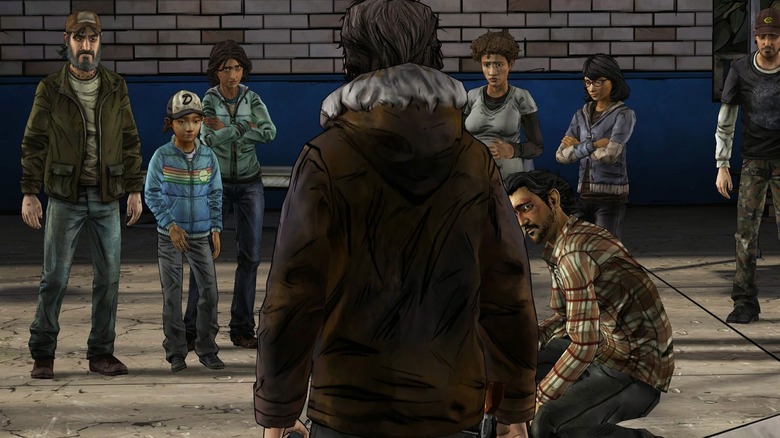

Fast forward to 2016, the height of the studio's output. In 2016 alone, Telltale was just finishing out Minecraft: Story Mode, but also put out The Walking Dead: Michonne, Walking Dead: A New Frontier, Batman's first season, and had already announced that Guardians of the Galaxy was happening for early the next year. Three high-profile titles, and two disparate additions to The Walking Dead, all within a year. Even for the more prolific publishers out there, that's a near impossible pace. The poor developers stuck jumping from project to project with no downtime absolutely agreed, and it shows in the work.

Never making a profit

All those extra projects Telltale was pumping time, money, and energy into might've made sense if Telltale was actually raking in the cash hand over fist from each one. In reality, just the opposite was the case.

As it turns out, even though the studio has generally seen critical acclaim for their projects, a Forbes writer citing an anonymous source within Telltale stated (in a since-deleted tweet) that only three of the studio's projects have ever seen an actual profit: the first season of The Walking Dead, Minecraft: Story Mode, and 7 Days To Die, which Telltale only published. The rest? A steady slope of diminishing returns, something corroborated by the sales figures from Steam (via SteamSpy). Walking Dead: Season One was actually an exception, not a rule as far as how well Telltale's signature brand of narrative adventure sells. The slump afterwards actually returned the company to the numbers it was raking in before The Walking Dead.

The sheer glut of titles just contributed to a sort numbness whenever a new Telltale project came about — dubbed in some corners as Telltale Fatigue — no matter how good the project actually was.

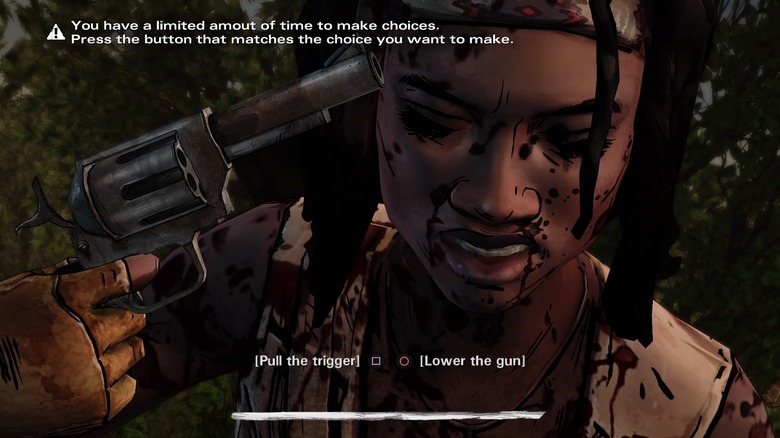

A stagnant engine

It didn't help matters that regardless of the narrative — Telltale's bread and butter — gameplay never actually felt significantly different from title to title. A few games introduced minor tweaks and gimmicks for sure, but nothing that fundamentally made, for example, playing as Batman feel any different than playing as Rhys in Tales from the Borderlands except for the suit.

There is a reason for that. Right around the time that Telltale's developers starting hearing the engine creak, Telltale's then-CEO, Dan Connors, stepped aside, and his replacement, Kevin Bruner, stepped in. Not coincidentally, this is around the time the aforementioned glut of 2016 occurred, as Bruner cracked the whip on content, with complaints about the aging Telltale tools falling on deaf ears. The tragedy is this was a problem the studio was on the cusp of fixing: The Walking Dead: The Final Season was slated as the last title to use the Telltale toolset. All projects going forward would have used good old reliable Unity.

Licenses, not sales, were carrying the company

While it was reckless, there was at least a bit of logic behind the studio's breakneck production schedule. Specifically, the fact that snagging high profile properties was essentially the only thing keeping the studio afloat.

The success of The Walking Dead: Season 1 was warranted, and it did lead the company to soar to new heights organically. The company snagged the respected, but not necessarily Batman-tier Fables license from DC comics to create The Wolf Among Us. They made a Poker Night At The Inventory sequel with some higher profile characters; one of which, Claptrap, led directly to the creation of the brilliant Tales from the Borderlands. And, naturally, they immediately started work on continuing The Walking Dead with Season 2 and 400 Days. When none of those projects were able to replicate Walking Dead's initial success, instead of cutting losses, and going back to aiming small, the studio doubled down, staying at their same financial strata with multi-million dollar money injections from cash cow investors.

Riding that wave comes at a cost, however. Whatever meager sales each game made anyway was still subject to residuals needing to be paid back to the licensee. While it probably didn't cost as much to pay Gearbox for Borderlands, paying back the likes of HBO and Marvel after failing to meet expectations cannot have been cheap.

They were never quite ready for AAA

A running motif, if you haven't noticed, is the fact that The Walking Dead: Season 1's success warped the perspective of Telltale's higher ups. It's not hard to see why, but the problem was that Telltale's corporate-side greed came without consulting the folks actually developing the games, many of whom were directly responsible for many of the ambitious decisions that made The Walking Dead what it was.

According to the incredible expose on the studio's woes by The Verge, "The poor reception for Jurassic Park meant the studio had little time to slow or halt development on [The Walking Dead]. The game had to come out, which gave the Walking Dead creative team leverage to ignore or skirt around feedback from upper management that they vehemently disagreed with. [Jake] Rodkin and [Sean] Vanaman developed a reputation as personalities strong enough to challenge the founders on creative decisions, and pushed over and over again to create the game the way that they wanted."

Once Walking Dead worked, however, the blood was in the water. Higher-ups expanded personnel and the production pipeline haphazardly, without taking the time to revamp any of their established processes. According to former programmer Andrew Langley, "We went from a small and scrappy team to kind of a giant studio full of 300-plus people. You walk around the office, and you don't really recognize anybody anymore."

Major talent jumped ship

On the flip side, while the company brought on a slew of new employees in the wake of Walking Dead, the major players who truly guided the ship towards glory churned out of the company like it was retail. Vanaman and Rodkin — who had been the strongest creative proponents on The Walking Dead: Season 1 — were the first out the door, but by 2017, most of the people behind the studio's greatest creative success stories were no longer with the company.

The result was chaos. According to The Verge: "Tribal knowledge persisted over clearly documented processes, and a lack of communication among employees bred confusion. 'Very rarely people were writing things down on a wiki or a confluence page or any sort of documentation,' says a former employee. 'People were shifting so often that you would hear a version of a story that was actually weeks old, and the person telling you has no idea because that's the last thing they heard.'"

In addition, none of Telltale's various series had their equivalent of a showrunner, someone with a clear vision of the shape of a series, and directly responsible for keeping it on track. The higher-ups' version of fixing clear problems with vision and development was, by all accounts, "add more people."

Studio crunch destroyed morale

Unsurprisingly, given everything else, crunch was a disease eating Telltale alive at its busiest times. Thing is, even as bad as crunch tends to be at major studios, where the final stretch of development requires long, unpaid hours of work, Telltale's breakneck production schedule essentially meant crunch time was ALL the time.

Former employees describe stretches where they worked 14-18 hours a day, seven days a week, with the end of one project bleeding right into starting the next. Sure, Telltale, like a lot of Bay Area tech companies, offered a lax vacation policy, but taking advantage wasn't exactly an option for developers who might take leave and come back to find out their project is now an unworkable disaster.

The biggest victims, however, were on the cinematics team, who were often graphic artists straight out of college, dealing with Telltale as their first experience. "You'd get a lot of people going, 'Oh I really want to prove myself, and I really want to make sure that they see that I'm contributing,'" says a Verge source. "The thing that broke my heart the most was seeing new team members that were just so gung-ho and optimistic and excited to be at Telltale get overused and abused because they did not feel comfortable drawing the line in the sand to say, 'This is my limit.' They either worked themselves out and would get sick or would become bitter."

The problems started at the top

While employees interviewed for The Verge's expose point fingers at management in general for their woes, many directly blame former CEO Kevin Bruner for the company's biggest problems.

The common explanation basically sees Bruner as instrumental in creating Telltale's game engine, but the studio's popularity went to his head early. He saw himself as Telltale's auteur. In reality, it was Sean Vanaman and Jake Rodkin fighting tooth-and-nail with Bruner that not only resulted in many of The Walking Dead's best ideas, but also resulted in the two fleeing the company shortly after the game released. Vanaman and Rodkin wound up founding Campo Santo, responsible for the critically acclaimed Firewatch. Later, another Telltale alum, Adam Hines, left to make Oxenfree, another well-regarded indie title. Fearing the company was making its own competition, Bruner tightened his grip on Telltale, resulting in, well, everything.

"He was hesitant to give anyone much credit for having significant creative vision," one Verge source says. "He thought they would leave and become a competitor because he had a couple of strong examples of people doing exactly that." According to another source, "There was a dark period of time where if you were in charge of a project, you are not getting any interviews. He's going to be the one on the panel. He's going to be the one doing the interviews. He's going to be the one in the magazine."

Turning the tide too late

It was only in the last year that Telltale had started to pull out of the slump. Kevin Bruner got the boot in early 2017, and new CEO Pete Hawley set about righting many of his wrongs. For starters, the company worked out a deal with Netflix to not only port some of its games to the streaming platform, but also produce a game based on Stranger Things.

Hawley also made the hard choice to lay off the extraneous portion of Telltale's staff Bruner had brought on. However, to his credit, that time, it happened the right way. The displaced employees were paid out for the rest of the year, allowing them the day to say goodbye to coworkers, and on-site job fairs were set up to help get them new positions at other studios. From there, Hawley was, reportedly, as hands off as the old guard had been when Telltale started, and the team's first major task was to put The Walking Dead to rest once and for all with a Final Season.

The problem was, it wasn't enough.

According to Variety, the last big deals keeping Telltale afloat were Lionsgate, AMC, and Smilegate. The death knell for Telltale came when those deals all fell through, leaving the company without its safety net, and the inability to fund Stranger Things, Wolf Among Us 2, or, as it turns out, the finale of The Walking Dead.

The audience just wasn't there

The story of Telltale is ultimately the story of hubris. While critics adored the studio's output, and they certainly had dedicated fans, the reality is that folks like Kevin Bruner wanted to pretend Telltale was about to become the next EA. The more realistic goal should've been to become the next Double Fine: a story-focused studio that could aim small, miss small, but keep doing their weirdo thing, innovating where it can. Double Fine is respected, but they're not AAA.

Instead, Telltale's brass kept trying to replicate The Walking Dead, without really understanding the things that made The Walking Dead special. Tellingly, both Batman: The Enemy Within and The Walking Dead: The Final Season showcased what a Telltale allowed to innovate looked like, and both were made after Hawley took the reins. But familiarity had bred contempt long before Hawley got the job, and the general consensus in the gaming community had become, "If you've played one, you've played them all." More than likely, this was the mindset that led Telltale's Batman games — an easy slam dunk if there ever was one — to flat out flop.

The kind of game Telltale made was always a niche. While that's a hard truth for those who love narrative experiences, Telltale operating as if that wasn't the case is the reason why we aren't getting any more of them.