The Untold Truth Of Five Nights At Freddy's

Five Nights at Freddy's served as a revitalizing jolt to the horror game genre. Slender Man had fallen to the wayside, since the character did not have enough backstory to keep players interested in the creepiness. FNaF came onto the scene in 2014 with a simple premise: survive some scares perpetrated by increasingly creepy pizzeria animatronics. Five Nights at Freddy's' jumpscare-laden gameplay, deep lore, and memorably terrifying characters made it an instant sensation. Because it was accessible to all ages, from the youngest to the oldest gamers, but still managed to confound skilled players and conceal secrets, it stayed in the spotlight where other horror games had failed. Scott Cawthon's now iconic series is the game that launched a thousand (or more) YouTube videos of let's players screaming, hundreds of Reddit threads theorizing on the games' true story, and even a movie deal.

FNaF sustained itself through many sequels, spinoffs, and a series of books. Chances are, you're aware of some of the games' eccentricities and secrets: the haunted animatronics, the Bite of '87, and other macabre tidbits. But, as commentators like MatPat of Game Theory quickly learned, when it comes to Cawthon's creations, there's always more to tell.

FNaF had its start in a Christian game

Five Nights at Freddy's is the unintended by-product of a previous game developer and creator Scott Cawthon had worked on, one that had a distinctly different premise than the nightmares of an underpaid Chuck E. Cheese worker come to life.

Cawthon first got his start in animating through Hope Animations, making the 8-part series The Pilgrim's Progress. It serves as "an allegory for the pilgrimage all followers of God must take" and features some of his early animations. It's his style of animation that actually led to the first seed of the idea behind FNaF.

Cawthon made several games before FNaF, and they were all family-friendly, some with Christian values at their core. A marked departure from the murder-ridden pizzerias of the FNaF games, Chipper and Sons Lumber Co. was cute, bright, and simple. His game The Desolate Hope made it through Steam's Greenlight process, but Chipper and Sons was criticized heavily for its animation. The smiley beaver characters were too stiff: they moved unnaturally, like animatronics.

In Cawthon's next game, he doubled down on the jerky movements while keeping the blank-faced, dead-eyed anthropomorphic characters. Unfortunately, the game was criticized for its "scary animatronic" aesthetic. From there, FNaF was born, and while there are no apparent Christian messages to be found in shady security offices, fans have been known to dig up more surprising secrets.

FNaF happened IRL... kind of

FNaF is riddled with tragedy. In the first game, we learn that the animatronics are piloted by the restless spirits of murdered children. This dark labyrinth of blood and lost lives goes deeper and deeper as the games progresses, all with the cheery backdrop of a children's party pizzeria.

But the virtual tragedy is an echo of the actual world. Like in FNaF with the infamous Bite of '87, real-life pizzerias have also witnessed violence and murder. In 1993, four people were murdered at an Aurora, Colorado Chuck E. Cheese. The shooter was 19-year-old Nathan Dunlap, who came in to have a ham and cheese sandwich and play some arcade games the night of December 14th. After close, the employees that remained were cleaning up. They were shot first, fatally. A third 17-year-old girl begged for her life on her knees, but was shot through the top of her head.

A manager was also killed after being forced to open the establishment's safe. Another employee was shot, but survived. He had just come in from his smoke break, thinking the gunshots were the popping of children's balloons.

Dunlap was sentenced to death, having carried out the murders as revenge for being fired from the Chuck E. Cheese.

Beyond the game

Don't let the fake trailers that periodically crop up on YouTube fool you: there really is a Five Nights at Freddy's movie in the works. Apparently it had been a popular bid before Warner Bros.-owned studio Blumhouse picked up the rights. The game-turned-movie had found a fitting place: Blumhouse is known to produce horror that terrifies. Blumhouse loves a franchise, and Freddy Fazbear's Pizzeria is a franchise tailor-made for multiple, spooky-scary productions that are sure to bring in audiences.

FNaF may be the video game movie that actually succeeds in the wake of countless failures. Blumhouse certainly has the credentials and the budget to bring the animatronics to jerky, dead-eyed life. And it has added Chris Columbus of the first two Harry Potter films, Mrs. Doubtfire, and The Goonies fame to direct all the action in the darkened halls of the pizzeria.

Fans who can't wait for the film and have consumed the ridiculous amount of FNaF content on YouTube can also satiate themselves with another addition to the Fazbear franchise: the book series. The Silver Eyes and later titles, The Twisted Ones and The Fourth Closet, give another perspective on the franchise. Cawthon has said that the books are in a separate canon from the games. This fact became a huge help to those digging into the mangled mess of secrets and stories woven throughout the games.

There's been a deeper story since the beginning

"Scott doesn't do jokes."

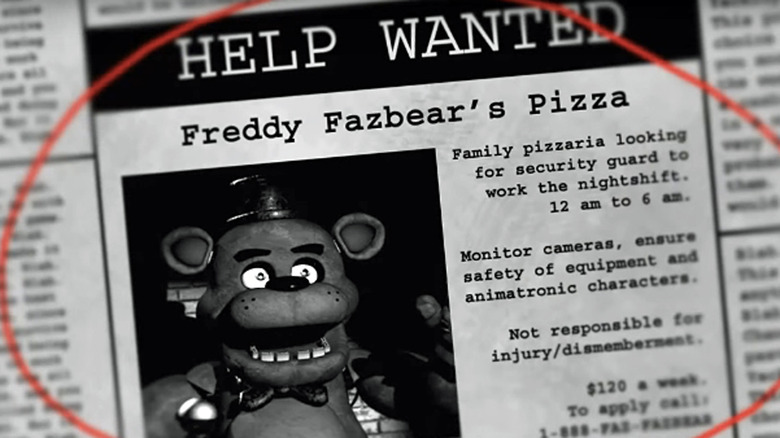

Or so insists YouTuber MatPat on his channel The Game Theorists. MatPat hosts dozens of videos wherein he untangles the intricate web of the Five Nights at Freddy's lore. The gameplay itself seems shallow, revealing very little as to what's going on beneath the surface. The first game has the player performing the duties of a nighttime security guard, fending off attacks from the animatronics who get "quirky" at night. It's only through little snippets and hidden newspaper clippings viewed through a security camera that reveals the backstory: there's missing children, parents complaining of "blood and mucus" coming out of the animatronics, and sketchy former employees behind the confetti-strewn facade of the pizzeria.

This is how the series tells its story. What really went on to create homicidal animatronics and haunting, lurching puppets is communicated through clues. There's a lot of these clues for deep-digging fans to find, if they're able to make it through all five nights, that is.

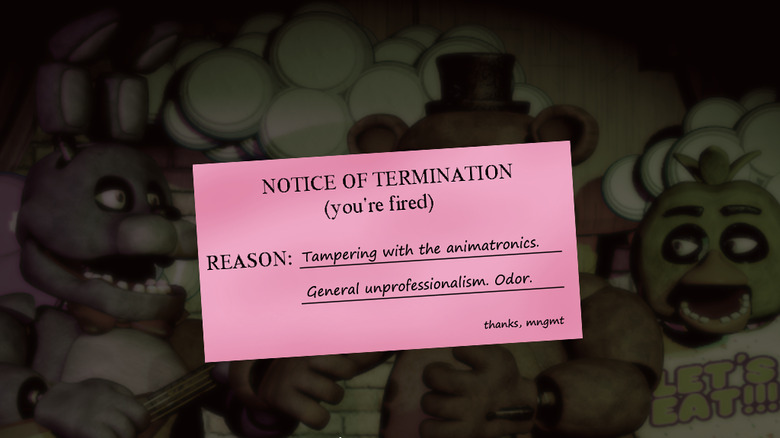

Even though the player is able to survive the onslaught of jumpscares, security guard Mike Schmidt is fired after the final, fifth night due to "tampering with the animatronics. General unprofessionalism. Odor."

We find out in way later games that "odor" might just be the key word on that pink slip. Which means that the very first game had the larger plot in mind all along.

It's a family affair

Mike Schmidt's real name is Michael Afton, son of William Afton, who created Fazbear Industries and with it the animatronics that terrorize the games. Fazbear Industries is something of a family business, with Michael continually trying to undo the sins of his father.

Michael returns to the Freddy Fazbear's Pizzeria that started it all in the first game. It was there that he bullied his little brother, who was (understandably) terrified by the animatronics. Michael put his brother's head in the — perhaps not structurally sound — Freddy's mouth which then bit down. The boy died later on.

Nothing stays dead in FNaF though. William Afton was using the fun of Freddy's and a springlock Bonnie suit to lure and kill children. One for each animatronic, into which their little corpses were stuffed. When his hunting ground is shut down after the infamous bite he opens the shiny Circus Baby's Pizza World. Complete with new animatronics, the place takes on a life of its own. Although he warns his own daughter Elizabeth to stay away from the clown Circus Baby, the little girl is eventually "scooped" and killed.

Getting scooped — which is exactly what it sounds like — is what later happens to Michael as well, making him into a flesh-suit for an animatronic. This is Circus Baby's, now possessed by Elizabeth, doing. The Afton family is finally put to rest by fire in the final game after years of haunting fur and metal.

The theorist vs the creator

The twisty timeline of the Afton saga has been painstakingly pieced together by MatPat. His longest-running, and perhaps best-known series, deals with all the miniscule hints Cawthon lays out in the FNaF games. His efforts aren't in vain either; his work has been acknowledged by the murder mystery mastermind himself. Through this, MatPat and Scott Cawthon have a sort of friendly rivalry, where one out-theories the other, always just a few steps behind.

MatPat doesn't always get everything right, and the solid truth of the FNaF story may not ever be fully fleshed out, but Cawthon has said that the Game Theorists channel gets "almost everything right." Still, the creator sometimes needles MatPat, commenting on videos with winky-faced comments: "It was a good video, MatPat; I always enjoy them. Unfortunately, as your more clever viewers are pointing out in the comments below, you overlooked a crucial detail in the game."

Cawthon has also crashed Game Theory livestreams, leaving tantalizing clues. To MatPat's frustration, he has a track record of revealing sequel titles or updating his usually blank site just in time for the release of a new FNaF theory video.

Cawthon has an interesting relationship with his rabid-for-more fan base. He does his best to provide enough content to satisfy, but sometimes the fandom's enthusiasm can prove to be too much.

Stop calling the pizzeria

The mysteries in Five Nights at Freddy's go beyond just the games. Even non-canonical content like the books can hold key insights for keen-eyed theorists. Any information that Cawthon puts out seems to be subject to intense, almost conspiratorial, scrutiny. This might be because Cawthon has been known to drop clues in unconventional places, such as on his site scottgames, a minimalist page that he used to announce new titles.

Avid fans quickly discovered that, as with the FNaF games themselves, behind the simplicity were secrets. Looking at the page's HTML code, there have occasionally been little nudges by Cawthon for fans to re-examine the evidence given in the games. One such hint on the fnafworld site even led theorists to scour over MatPat's own videos. "What is paragraph 4?" Could it have referred to the fourth paragraph in a Game Theory script?

Ultimately, this led fans in many directions. Harmless ones. But one hint went sideways fast, with real-world consequences. The numbers 8 and 7 appeared a suspicious amount on scottgames, perhaps hinting at the "Bite of '87." Super sleuths plugged these repeating numbers in as coordinates and discovered the location of a pizza place in Virginia.

Finding a review that seemed to verify the involvement of murderous animatronics, fans bombarded the restaurant with calls. It came down to Cawthon having to make an exasperated statement, pleading with FNaF fans to stop calling the pizzeria.

The fandom became too much for the creator

The pizzeria incident and the general foam-mouthed ferver the fandom can whip itself into has led to Cawthon having a sort of strained relationship with the series as it continued onward into further iterations. All those theories and long, long threads of FNaF subreddits, the YouTube videos and Let's Plays, became a mounting pressure to provide fans with more to discuss. Eager and overbearing at times, Cawthon may have felt as if the fandom was breathing down his neck.

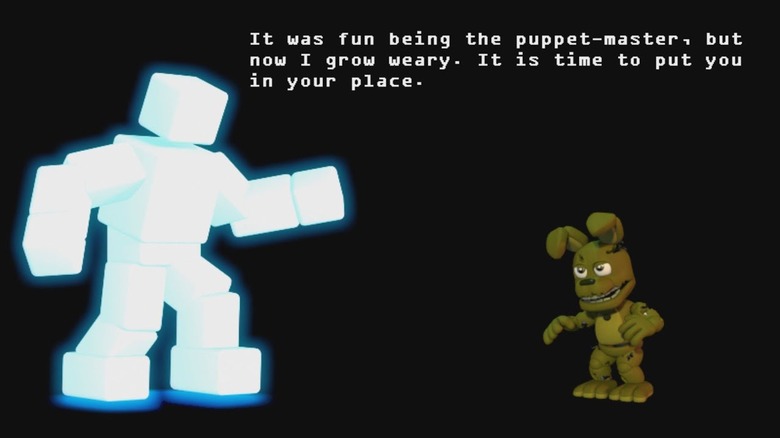

This frustration may have been expressed through a final boss in FNaF World. The game wasn't as well-received as his other games, but it nevertheless, was laden with the same care to carve out secrets as the other games were. One of these secrets was Cawthon himself, who says to the overachieving player, "So it's your fault then, for my misery. It's never enough for you people. Don't you get it? I can't do this anymore! I won't ..."

Eventually, Cawthon canceled the sixth title in the series. Though he later released Freddy Fazbear's Pizzeria Simulator, he admitted that he no longer wanted to work on FNaF titles, feeling that he always needed to make the next game bigger and better than the last. This cycle proved straining on his personal life. Whether those feelings persist after his releasing the spinoff Ultimate Custom Night this year, it's clear the popularity of the FNaF world is a burden on its creator.

What's in the box?

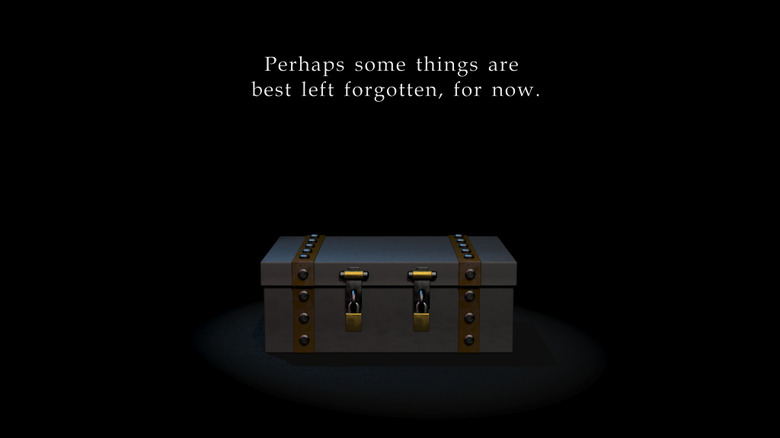

The end of FNaF 4 leaves the player with one final image: a box with two locks, and the text, "Perhaps some things are best left forgotten, for now." What about later? What's in the box?

Cawthon first considered opening this box for fans in the update that came just a month after its reveal, but decided to keep that secret locked. He said that he first created the box as an alternative to all the Easter eggs he usually littered his games with. He wanted the secrets to be harder to crack than they had been in the previous titles.

"What's in the box?" he wrote on Steam. "It's the pieces put together. But the bigger question is — would the community accept it that way? The fact that the pieces have remained elusive strikes me as incredible, and special, a fitting conclusion in some ways, and because of that, I've decided that maybe some things are best left forgotten, forever."

It feels definitive, considering that Five Nights at Freddy's 4 was meant to be the last chapter of the series. When MatPat dedicated a livestream to theorize on this, Cawthon came in with some hints, apparently disappointed that no one had yet uncovered the truth he had hidden.

The box is all his clues put together into the definitive story. In the sixth and final game, the box is mirrored in the trap that burns the Afton family away at last.

What's dead is never gone

The untold Afton story unites the games into one, perhaps blurred, but complete nightmare. Cawthon was careful never to be too direct, but the sixth game seems to wrap up the narrative into a neat, burning bow. Afton's partner Henry got revenge for his murdered daughter and put her, the other children's, and finally the Afton family's spirits all to rest by setting the pizzeria ablaze.

But why did this all happen? Was this all a result of one man's madness? Yes, and no. The thing is with the FNaF games is that Afton was a genius, unfettered by ethics, but nevertheless a genius. The events of FNaF aren't just a haunting — they're scientific necromancy.

Afton was playing god. He made a discovery that human life could be sustained in the animatronics. To confirm it, he took his theory to animal testing. He killed a girl's dog, and placed its spirit in Mangle. Mangle is the only animatronic to be animated without the usual human traits that Freddy and his gang exhibit.

The possession of the animatronics by the murdered children isn't coincidence, but intention. Afton just didn't realize that they would be murderous in return, and come after him. As the series has thoroughly demonstrated and as MatPat likes to insist, "Scott doesn't do coincidences."