Times The Video Game Industry Seriously Cheated Gamers

You probably wouldn't be here if you didn't enjoy video games at least a little bit. Fans of the medium come from all walks of life and have their own reasons for playing, whether it be for a story, a challenge, or a way to gather online with friends. And there are plenty of people in the video game industry who love creating these experiences for players. It's the reason they work long hours and deal, at times, with a whole lot of vitriol online.

But not everyone in the industry is a white knight. Those who buy consoles and games are right to be a little skeptical when it comes to what's promised and delivered by game companies — especially those with a proven track record of questionable behavior. We've put together a list of several instances where the video game industry has cheated its fans, and by doing so, harmed the relationship between game companies and gamers.

Proprietary storage

Can you believe there was a time we couldn't use external hard drives on our consoles? It's true! The video game world wasn't always so fond of plug-and-play solutions like USB storage. Instead, we were forced to endure a parade of proprietary solutions that were designed to gouge consumers at the cash register.

The Xbox 360, for example, used a specially-formatted hard drive inside a plastic housing. This made it incredibly difficult for gamers to use their own hard drives and allowed Microsoft to charge far more for its hard drives than anyone else. Sony is also famous for its proprietary storage, as owners of the PlayStation Vita will gladly tell you. In fact, many believe the Vita was partly hampered by its custom memory cards, which wound up costing a whole lot more than MicroSD cards with the same amount of storage.

Thankfully, ubiquity won the day. Most game consoles are now able to use USB hard drives and thumb sticks, driving storage costs down significantly.

Vague "season passes"

One might feel compelled to say that downloadable content, also known as DLC, is itself a way to cheat gamers. But we'll put that belief to the side for now and instead focus on a by-product of the DLC era: season passes. You've undoubtedly seen these passes advertised during the hype cycle prior to a game's launch, and at first glance they seem like great deals. You can pay one price now and get a whole lot of DLC at a discounted rate. Pretty good, right?

Here's the problem: many games don't go into detail about what exactly you're getting with a season pass. The company behind the game may not have even created the content yet, or it might not want to share what the content is. You're essentially gambling when you buy a season pass, because you're hoping the DLC feels worth the money you spent for it in the end. This is how people end up purchasing a Batman DLC with the hopes they'll get more story missions, but they get a bunch of character skins and "time attack" modes instead.

DRM in digital games

DRM, short for digital rights management, is what content companies use to ensure a consumer has actually purchased a digital product. We see DRM in use across a variety of digital items, including songs, movies, e-books, and video games. And while DRM may sound reasonable in some instances — such as preventing unauthorized copies of a product from being made — DRM largely strips away the rights we've enjoyed with physical media for such a long time.

Game companies try to make digital copies sound nice by touting features. You can play your game without a disc! You can download your pre-order days before the game launches! But the truth is, buying a digital copy with DRM in place means you give up a number of different perks. You can no longer lend your games to friends. You can't sell a game if you decide you don't like it, or if you want to trade it for credit toward a new game. And should you lose access to your account, or get banned from an online network like PSN or Xbox Live, you could lose access to your purchases.

When you buy a digital game, you don't own it. You have a license for use. And game companies like Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo can all dictate how and when you're able to use the game you paid for. All thanks to DRM.

Unreasonable review embargoes

Just as news journalists keep us informed and hold governments accountable, video game journalists serve a purpose for our collective hobby. They make sure we're in the know about the latest developments in the video game industry, and they travel to and fro to cover games that are planned for release in the future. On top of that, they act as a check to the games industry as a whole.

Reviews are a way for games journalists to look out for the buying public. If something is worth buying, they'll let you know. And if something should be avoided, they'll let you know that, too. For the most part, publishers and developers understand this and work well with websites and magazines that cover games.

Unfortunately, there have been instances where video game companies have not played ball. They've purposely held games back from review by imposing unreasonable embargoes: for example, not allowing writers to release a review until after the game goes on sale. These practices ultimately harm consumers and allow bad games to hit store shelves before critical thoughts can have an impact.

If you see that a game is purposely delaying reviews until after launch, hold off — it's probably doing so for a reason.

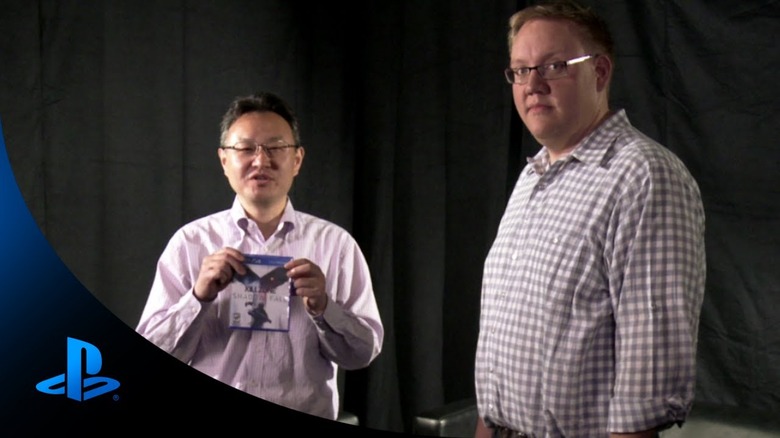

Platform-exclusive content

If you went to McDonald's and ordered an Extra Value Meal, you'd probably be a little bothered if the customer right after you ordered the same meal and got an extra cheeseburger for the same price. Welcome to the world of console-exclusive content, where platform companies like Microsoft, Sony, and Nintendo strike deals with publishers to get extra content for their systems.

The best — and most despised — example of platform-specific content in recent memory has to do with Destiny. Since the franchise launched back in 2014, Sony has had a marketing partnership with Destiny, paying money to Activision in exchange for exclusive content. Every time a new Destiny game or expansion pack comes out, PlayStation consoles get extra game missions and exclusive loot, while Xbox and PC players — who pay the same amount of money for the game — are left out in the cold.

Platform-exclusive content essentially cheats players on other platforms. Not only that, it encourages the highly toxic "console fanboy" mindset that doesn't do the game industry any favors.

Loot boxes

Somewhere along the way, game companies decided that simply paying for the downloadable content you want was too fair. Why let you directly purchase that character skin you want, or that emote you're dying to have, when you can dump endless amounts of money into a virtual slot machine for a chance to get that item instead?

Loot boxes are, for better or worse, games of chance that now exist inside video games. And they're a plague.

Now, let's not kid ourselves: we could find plenty of people who take issue with microtransactions in general. To these folks, game companies are trying to charge more for content that should have been included at the start. That's certainly an argument that can be made. But loot boxes take the concept of microtransactions and put an entirely unfair spin on it, asking players to buy these "boxes" with real world money with the hopes that their box contains the thing they want.

What often ends up happening, though, is that highly desirable items show up less often in loot box rewards. And some less disciplined gamers may find themselves spending a whole lot and getting a bunch of stuff they don't want, all in pursuit of that one thing they crave. Loot boxes are designed to take advantage of gamers, and they've got to go.

Online passes

We discussed earlier how digital rights management (DRM) is designed to lock gamers into their purchase and give platforms massive amounts of leverage. Now that more and more games are played online, server access can itself act as a form of DRM, too. Several years ago, EA figured this out and devised a plan to both make used games less valuable and ensure it would still profit from used games in the process. That plan brought us "Online Passes."

EA's Online Pass system essentially hid access to online servers behind a paywall. Those who purchased a game at retail would get a code for the Online Pass service, but if they chose to sell their game at a later date, their Online Pass could not be transferred. Further, anyone who purchased a used EA Sports game at a store like GameStop would also need to pay $10 for a new Online Pass. No Online Pass? No online play.

Fortunately, EA's system was not well received, and the company did away with it after the backlash. But there's no guarantee we won't see a similar system again in the future.

Reneging on hardware support

Gamers are always looking for new ways to play games, and console peripherals can serve to augment an already-existing game experience with new features. The Kinect for the Xbox 360, for instance, added voice control and motion-powered gaming to Microsoft's second console, and it sold like gangbusters. Hardware accessories are great when they're supported. It's when they don't get support that gamers have a legitimate bone to pick.

The Kinect for the Xbox One is a shining example of how a company can cheat gamers by not supporting hardware. Microsoft bundled the Kinect with its Xbox One at launch, and the added cost made for a fairly expensive console package. But the Xbox faithful bought into the system anyway, and just a few years later, they have very little to show for it.

After getting blown out by the PlayStation 4's sales, Microsoft unbundled the Kinect from the Xbox One to better compete on price. When the Xbox One S arrived a few short years later, the Kinect required a special adapter in order to connect to the system. And by the time the Xbox One X rolled around, Microsoft had stopped manufacturing the special Kinect adapter entirely. The Kinect is now dead hardware, and for gamers who paid $500 at the Xbox One's launch, that can't sit well.

Pay-to-win microtransactions

We've hit on how crappy loot boxes are for gaming. They're randomized microtransactions, and they only exist so that people spend more money than they have to. But would you believe that there's an even more dastardly form of downloadable content in the world? There is. They're called "pay-to-win microtransactions," and they're bad news.

Imagine this: you buy a game, you jump into a multiplayer match, and you're having a great time. Everything seems totally fair, and you feel like you're winning and losing based on your skill. You feel like you have an incentive to get better. It's the exact feeling a video game should deliver to you, and you're happy with your purchase.

Then you lose: badly. You're not sure how. You were playing better than the other guy. But his guns felt... stronger? Or maybe he had a bigger health bar than you did? That doesn't seem very fair. But that's life in a game with pay-to-win microtransactions. If someone is willing to spend more money in a game than you are, they're going to have the upper hand.

Star Wars: Battlefront II actually started out this way, and believe it not, actually mixed both pay-to-win microtransactions and loot boxes to wring the most possible money out of its players. Only a community revolt caused EA, the game's publisher, to backpedal and revamp its progression system to be more fair.

Crowdfunded games that were never completed

Crowdfunding websites like Kickstarter can open the world of video game development up to a whole new, well, crowd. They let amateur and newly independent developers find their footing and fund projects without having to take on investors, and there are some great success stories that have come from crowdfunding campaigns.

But with the good comes the bad, and there are way too many stories about crowdfunded video game projects that have disappeared, leaving those who funded them without their money or a new game to play.

Moon Rift, for example, raised over $8,000 nearly five years ago. No game. Code Hero ran a crowdfunding campaign in 2012 and raised over $170,000. No game. Yogventures garnered an astounding $567,665 that same year. No game. And what else do these games have in common? If they weren't canceled outright, as was the case with Yogventures, they simply faded away, and those behind the crowdfunding campaigns weren't even willing to issue an on-the-record comment to backers.

If you see a game you may be interested in doing a Kickstarter or a GoFundMe, exercise extreme caution and enter with the most skepticism you can muster. Crowdfunded video games are a lot like loot box items: even if you pony up the money, the odds of you getting what you want are slim.