Disastrous Video Game Development Decisions

When a company is developing a video game, dozens of decisions large and small go into the process. Video games are complicated beasts, and one askew decision can throw a hitch into perfect plans. Nobody sets out to make a bad game, but bad games still get made. More alarmingly for developers, disastrous games, the kind that set a company back (and occasionally destroy them), happen as well.

In the annals of video game history, there are development decisions that stick out for how they confounded, and sometimes infuriated, gamers worldwide. Sometimes it's a series of poor choices that all coalesce into one disaster. Sometimes it's a terrible decision that leads to a cavalcade of failures. Here are ten of the most disastrous game development decisions ever. They turned promising ideas into lackluster results, made gamers scratch their heads, and in one instance spawned a documentary dedicated to its monumental failure. Hey, how many video games can say that?

Duke Nukem (Takes) Forever

When Duke Nukem 3D was released in 1996, it was a reasonable success, even if it courted controversy with its "sex and violence" ethos. Naturally, a sequel, Duke Nukem Forever, was announced in 1997. Then, the game found itself stuck in development hell for over a decade. As a Wired article about the protracted process of making Duke Nukem Forever notes, developer 3D Realms spent a whopping 12 years working on the game. That's insanely long for a video game. It was thought that the fourth Duke Nukem entry would never come out; it would disappear into the realm of vaporware.

In 2009, 3D Realms, still not having finished the game, closed up shop. They were sued by Take-Two — who had the publishing rights to Forever – for not delivering the goods. This sequel effectively destroyed the company.

Here's the cruel irony of it all: Gearbox took over for 3D realms and, in 2011, finally brought Duke Nukem Forever into the world ... and basically everybody thought it sucked. It was clear that the game had been in development for 15 years. Time had not been kind to Duke Nukem, and somehow it was still laden with technical problems despite taking a decade and a half to enter the world.

Bomberman gets gritty

When you think of "Bomberman," you probably envision a cute little guy with two black lines for eyes, a blue-and-white outfit, and pink hands and feet. To the extent he has a personality, it's a cheerful one. This worked just fine for Konami, but suddenly in the mid-2000s they decided to chase a dragon that has brought down many an intellectual property: they decided to give Bomberman a gritty reboot.

Gritty reboots have been done so often in pop culture they are a punchline at this point. You'd think that a Bomberman gritty reboot would be such a joke, but Bomberman: Act Zero is all too real. The cover art for the game is self-parody, and the happy little Bomberman we all know and love is gone. He just looks like a reject from a Halo ripoff. In their review of the game, IGN called Bomberman: Act Zero "an unqualified failure." They weren't the only ones. Both critics and fans despised the change in tone. It turns out nobody wanted a gritty Bomberman. The next time Bomberman appeared in a game, he was back to normal. Konami learned their lesson.

It's a bird, it's a plane, it's a terrible Superman game

The magazine Nintendo Power was created by Nintendo to promote its games, so when they say a game is the worst ever on a Nintendo platform — which they did in 2005's issue 196 — that means something. It's Superman, a 1999 offering for the Nintendo 64, that earned that designation. Here's just one example of its failure: the game opens with a ring maze sequence for which players have zero preparation. Making matters worse, it comes with a time limit, putting you under the gun. The real problem is that the controls for Superman were legendarily terrible and the game was exceedingly glitchy.

Adding to the confusion and frustration is that the game inexplicably takes place in a virtual reality simulation of Metropolis. One of the producers from Titus Software discussed the issues with the game (transcribed partially by Kotaku here). He said that the licensor of the Superman brand — in this case probably Warner Bros. — refused to allow the Man of Steel to hurt "real" people, hence the virtual reality. The producer also added, "It is not even 10% of what we intended to do, but the licensor killed us!"

So maybe the disastrous decisions here were made by Warner Bros. as opposed to the developer. Then again, maybe it was a bad decision for Titus to try and make this game under these strict confines. They probably should've said no the second they heard the words "virtual reality simulation of Metropolis." Unfortunately, it's too late to do anything about it for Superman — and for Titus, who went out of business in 2005.

Daikatana's marketing gets weirdly aggressive

Nobody likes to be told that somebody wants to make them their b***h — at least when it's not consensual (no judgments here). That's what made the ads for Daikatana so perplexing. John Romero was a big name in video game development: he had worked on Doom, Wolfenstein 3D, and Quake. People wanted to play his games. They didn't want to be his b***h.

And yet, promotional posters for his 2000 game Daikatana threatened just that. They simply read, "John Romero is about to make you his b***h." That's awful on several levels, and even Romero has come to realize that. In an interview with Gamesauce, he apologized for the ads, but the damage had been done years prior.

To add insult to injury, Daikatana kind of sucked. The game was a commercial failure, one of the biggest in PC gaming history in fact. Ion Storm's Dallas office closed thereafter, perhaps because they had made a $25 million game that reportedly only sold 200,000 copies.

Interplay gives up on Fallout

The Fallout series is one of the biggest video game franchises in the world. Its rights used to belong to Interplay, but the key words in this sentence are "used to." Back in the '90s, Interplay released a couple Fallout games, and had planned to make Fallout 3. However, the company decided to abandon their Fallout 3 plans to put all their eggs in the basket of Brotherhood of Steel, a PlayStation 2 game that did merely alright.

Then, the problems began. As Venture Beat notes, Interplay started to have serious financial issues in the early 2000s. They were delisted from NASDAQ in 2002 and had problems paying their staffers. In 2004, they were evicted from their own property, and then in 2005 their parent company Titus (remember them?) declared bankruptcy. Interplay survived, but in 2007 they had to sell off the rights to everything Fallout related to Bethesda. Bethesda would in turn actually make Fallout 3, and the rest is history.

Unfortunately, Interplay is also history. You can't help but wonder what would have happened if they had just stuck to their guns and made Fallout 3. They spent money and time on that game, which became a sunk cost when they opted to make Brotherhood of Steel instead, which did nothing to help them financially. Given how successful Fallout 3 was for Bethesda, maybe that game could have saved Interplay. Talk about a Sliding Doors moment.

Philips enters the video game world, immediately get in over their head

When Nintendo decided to not add a CD-ROM element to the Super Nintendo, they apparently figured there was no harm in licensing some of their characters to Philips for their new CD-i system. So Philips got the rights to Mario, but also the world of Zelda, with Nintendo essentially having no involvement. That's pretty obvious once you see the games.

Philips released two Zelda games in 1993 on the same day. The first two games, Link: The Faces of Evil, and Zelda: The Wand of Gamelon, are particularly maligned for their truly horrendous, and occasionally nightmarish, cutscenes. Stephen Radosh, the man who helped bring video games to the CD-i, described the process to Game Informer: "Because animation at that time was really expensive here, we opted for this hand-drawn look for those games. We wound up with Russian animators. We'd send them vague storyboards and gameplay, and then [Russia] would say, 'What do you think of this for a visual concept?'"

Matthew Castle of Computer and Video Games succinctly called the animation, "terrifying, rendering Link as a rubbery limbed freak with a face that swims all over his head." He's not the only one who thought that, and the CD-i became one of the bigger failures in video game console history. Why did Philips decide to spend all this money on the rights to iconic characters like Link, only to clearly rush the games out? In that same interview, Radosh said that Philips' system wasn't designed to play video games. So trying to make games for it seems like a pretty baffling decision.

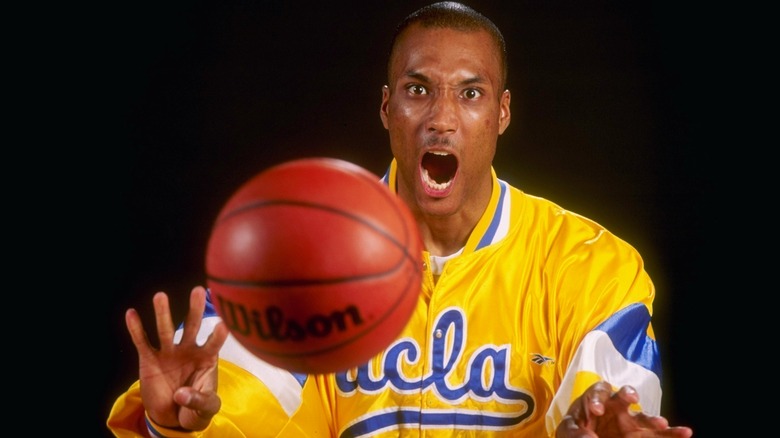

EA Sports doesn't compensate college athletes

A lot of people make noise about the fact that colleges and universities make a ton of money off the backs of their athletes, but said athletes don't see a dime. In fact, it's often a violation for somebody to even buy a football player a suit or a sandwich, because the NCAA is insane (and a cartel, but that's neither here nor there). Back in the day, EA Sports decided they wanted in on that good, old-fashioned exploitation. They made popular college football and college basketball games for years, until the time came to pay the piper.

Former UCLA basketball player Ed O'Bannon joined up with some other former college athletes to sue the NCAA and EA Sports for using their names and likenesses without their consent. As the New York Times reported at the time, a settlement led to the plaintiffs getting a whopping $60 million. That wasn't the end of the damage done to EA Sports, though. After the conclusion of this lawsuit, they haven't made a single NCAA sports game since 2013. That money-making enterprise is apparently dead. Still, given that they were using the likenesses of literally hundreds of athletes without compensation, you can't feel too bad for them.

SimCity ties itself to the internet

When Maxis decided to reboot SimCity in 2013 for the modern era, people got excited. Hey, as long as you can still have a monster come along and destroy your metropolis, it's got to be fun, right? However, there was one little issue with this new version. As Kotaku noted, you had to be online. Like, all the time.

Yes, the new SimCity required you to be online to play. This sucked in simple ways, such as making it impossible to play on a plane, the perfect place to kill some time. However, this also meant you couldn't play if EA (who owned Maxis) had issues with their servers. Naturally, when the game launched, they had a ton of problems.

For days nobody could play SimCity, because they couldn't get on the servers, and there was no offline mode. Fans went nuts, and reviews were extremely harsh. It was a total disaster. They had to hurriedly put together a single-player offline version to appease the angry mobs. Maybe they should have just done that in the first place.

Battlefront II's loot boxes blow up in EA's face

Hey, when you're a massive company like Electronic Arts, you're bound to have some major blunders over the years. It's only due to their size that they've managed to make it through the mess each time. However, that doesn't mean the impact hasn't been felt within the company. Take, for example, the loot box controversy that exploded upon the 2017 release of Star Wars: Battlefront II.

What was the problem? According to Kotaku, the game encouraged players to spend actual cash for the chance to earn in-game advantages, packaged in "loot boxes" that held randomized rewards. That randomization seemed tailor-made to part players from their money, effectively turning a Star Wars shooter into a digital slot machine. Critics and players cried foul, and the internet exploded.

Before the game could officially launch, those microtransactions had to be removed because of the online outcry, according to IGN.

The immediate results of the controversy were impossible to ignore. Not long after the bad press erupted, CNBC reported that EA's stock took a $3 billion tumble.

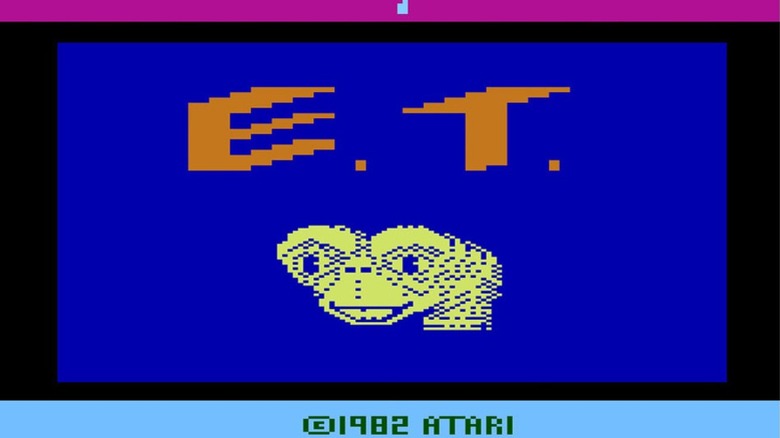

Atari's E.T. game. Need we say more?

It's perhaps the most infamous failure of them all. Steven Spielberg's film E.T.: The Extra-Terrestrial proved extremely popular with moviegoers in 1982. As such, Atari desperately wanted to get an E.T. game out for the 1982 holiday season. The problem, as Snopes notes, is that decision gave them only five weeks to code the game. It was the ultimate rush job, and it showed. The game looked terrible, but, more pressingly, it was basically impossible to play.

Atari initially produced an incredible five million copies. They sold only 1.5 million, and many of those were returned due to intense frustration with what a garbage game it was. That's a fitting adjective, too, given the fate of most of the copies of the game: truckloads of E.T. cartridges were buried in a landfill in New Mexico, only to eventually be excavated decades later for the sheer kitschy glee of it. GamePro called it one of the most important video games of all-time. Alas, that's because some consider it the beginning of the video game crash of 1983.

E.T. is the quintessential example of how one decision can lead to epic disaster. Many games suck. Few end up in a New Mexico landfill.