The True Story Of The Sega Saturn

Today, Sega is a video game publisher that owns a variety of studios, from the hedgehog-tamers at Sonic Team to the strategy veterans at Relic Entertainment. But once upon a time, Sega was so much more, one of the titans of the entire industry. In this golden era, Sonic wasn't just another game character, but a mascot for the whole medium. Their success had no end in sight, and only the sky was the limit.

So what happened? How did Sega go from hardware-producing juggernaut to mid-sized software publisher? Why aren't we all still playing on Sega consoles today? The answers all lead back to one specific platform: the Sega Saturn. It was the first of a new generation of consoles, the start of a whole new era of gaming. And yet, a number of mistakes and bad decisions turned the Saturn into the tombstone of Sega's ambitions. It's not that it was a bad system, or that there weren't great games for it — it's that contrasting orders from upper management pulled it in too many directions at once. This is the true story of the Sega Saturn.

In the beginning there was Genesis

The Sega Genesis was the company's third attempt at a home hardware release, after the SG-1000 in 1983 and the Master System in 1985. But neither of these consoles made much of a splash in the marketplace, as the dominance of the Nintendo Entertainment System proved unassailable. But in 1988, Sega released their 16-bit console, called the Mega Drive in Japan, a full two years before their rivals at Nintendo would release their own 16-bit machine. And when that system released in America, rebranded as the Genesis, Sega's fortunes at last began to turn.

With that two-year head-start on Nintendo, the Genesis established itself as the most powerful console on the market. Better yet, Sega had finally come up with a brand-defining character in the same way that Nintendo had. Sega's mascot was a vibrantly blue hedgehog named Sonic. The Sonic the Hedgehog series became legendary for its ultra-fast-paced platforming and charming characters. Critically, the Sonic series, and Sega as a whole, established a "too cool for little kids" vibe that distinguished it from the family-friendly Nintendo.

Even once the 16-bit Super Nintendo finally arrived, Sega continued to find enormous success. There were now only two viable hardware brands in the entire industry, and Sega was half of them. But they knew full well that they would have to keep innovating to stay ahead of their rival — and that instinct would lead them into disaster.

Expansions to the Genesis flopped

Since the Genesis itself was a popular machine, Sega's first instinct was to use it as an expandable platform. In other words, instead of rushing a brand new console to market, they would create add-on hardware that could be used with the 16-bit system.

On paper, it's not a bad idea: the Genesis' existing install base could be converted into brand new revenue. In practice, none of it worked. At all.

First up was the Sega CD in 1991, which was meant to transition the Genesis off of cartridges and onto compact discs, a newfangled technology that provided far greater storage space. While this meant that games could be bigger and higher-resolution, unfortunately for Sega, very few games were actually produced for the add-on. Without a deep content library, the hardware extension simply never found an audience.

Next up was the Sega 32X, which enabled the 16-bit Genesis to play 32-bit games. This finally brought true 3D gaming to consumers, and allowed for more impressive games in general — at least, in theory. The add-on was just as expensive as the core Genesis itself at launch, and like the Sega CD before it, there weren't many games available. Worse, since developers knew Sega was working on a full-on 32-bit console, software studios didn't know which console to develop for. In the end, most just gave the 32X a pass, which meant customers gave it a pass, too.

The Saturn could have stopped the PlayStation from ever happening

The Sega CD add-on hadn't worked out very well for Sega, but it did establish an important partnership. Sega's engineers hadn't known very much about CD technology, so to build the new hardware, they turned to another electronics company that did: Sony. While sales of the Sega CD were poor, the actual tech in it was pretty good. Knowing CDs were the future, Sega of America CEO Tom Kalinske proposed a radical idea to his bosses in Japan: to develop their next console in partnership with Sony. That way, the two companies could split the costs, and produce a shared console at the very highest technical standards.

Too bad, Sega headquarters shot down the idea. Upper management knew they'd lose money on each unit of the next-generation console they sold: the plan was to make all their profit off of the strength of the games themselves. And since Sega had more experience producing games than Sony did at the time, the partnership seemed to benefit Sony more than Sega.

Of course, Sony didn't let this dead deal stop them. They would eventually release their own console, the PlayStation, in 1994. And wouldn't you know it, it used CDs. If Sega had only agreed to the partnership, the PlayStation and its long lineage of consoles and games might never have happened at all.

Sega's new console met fierce competition… from Sega

The company pressed ahead with plans for its own new console: the Sega Saturn. Unlike the 32X, it would be a true 32-bit machine running off of CDs. The plan, once again, was to beat Nintendo to market and hopefully repeat the Genesis' strong early performance. However, there were apparently some questions being asked in the upper echelons of Sega's management. Cartridge-based consoles had always been the industry norm; what if game developers, or even audiences, wanted to stick with those and not switch to CDs? Sega CD, after all, had been a failure.

So internally, Sega devoted resources towards another 32-bit console, one using cartridges instead. Codenamed Jupiter, it would effectively feature the same chips as the Saturn. In principle, it could run the same games. Sega management allegedly went through a few possibilities for how this might play out on the marketplace: perhaps both consoles would be released as options, or maybe add-ons could be used to make them cross-compatible.

However, this meant Sega was effectively now developing, and trying to convince external studios to support, three different 32-bit systems: the 32X, the Saturn, and the Jupiter. With Sega's plans still shifting the months before the Saturn's release, game designers were left in the lurch. In the end, the Jupiter was cancelled, but the scattering of resources and focus could only have detracted from making the Saturn the best console it could be.

The Saturn aced its Japanese premiere

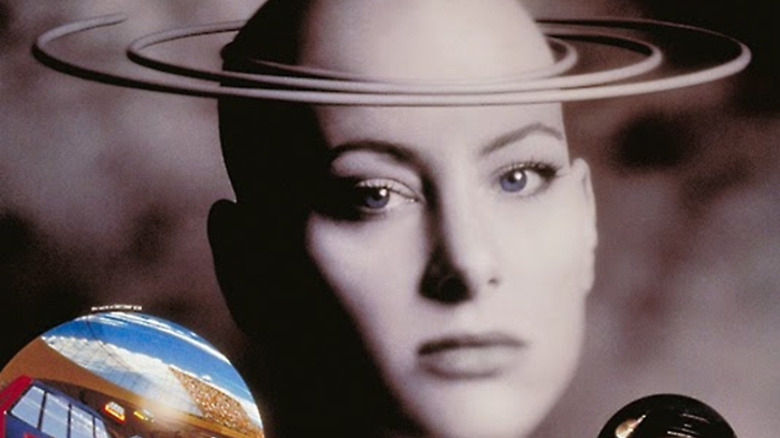

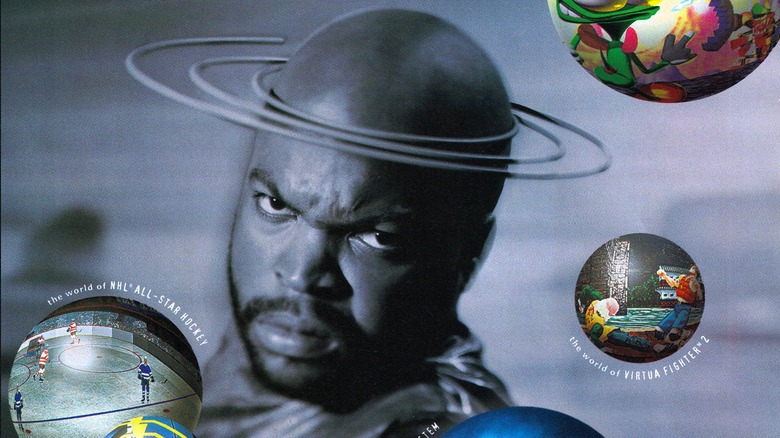

But all seemed well when, in 1994, the Sega Saturn finally debuted in Japan. Immediately, all 200,000 units sold out. Sega was the first big-name hardware developer to release a 32-bit console, getting ahead of old rival Nintendo and new rival Sony, with the first PlayStation still in development. The more powerful CPU was able to handle 3D gaming and render polygons at a smooth framerate, a whole new graphical direction that the entire industry would soon follow.

At launch, the main showcase for that horsepower was a port of the popular arcade game Virtua Fighter. There was no other home console that could play something that looked that good, which led to the console's fantastic early reception in Japan. And yet, beyond Virtua Fighter, there wasn't much to recommend the Saturn. Sonic the Hedgehog, the company's mascot, was nowhere to be seen, and in fact, would never arrive on the console at all. Sega had put a Sonic game for the Saturn into development, but it had been cancelled, leaving a massive hole in the system's lineup.

Despite the solid premiere, these gaps in its library were a vulnerability for the Saturn and for Sega as a whole. The Sega CD and the Sega 32X had both been killed off by their lack of games. If the Saturn repeated the problem, Sega could be overwhelmed by hungry competitors. And as it happened, Sony in particular smelled blood in the water.

The Saturn shocked E3, for better and worse

After the Saturn's successful Japanese debut, Sega turned its attention towards the all-important American market, the largest gaming audience in the world. The Electronic Entertainment Expo, or E3, was the biggest trade show in the world for gaming, and Sega wanted the Saturn to dominate the event. However, Sony would also announce the American release of its console, the PlayStation.

Desperate to beat the PlayStation to the US, word came down from Sega President Hayao Nakayama himself that the Saturn had to be available after E3. As in, immediately after. As in, on the same day.

Sega of America CEO Tom Kalinske thought that strategy was insane, since he knew they wouldn't be able to physically produce enough consoles in time. Nevertheless, he dutifully went to E3 and announced to the world that the Saturn was not only coming, but had already arrived.

But there was bad news, too: namely, the price. The Saturn would launch at $399, a hugely expensive price for the time. Sega was, once again, banking on an early release as the key driver of sales, regardless of price. In theory, if the Saturn were on store shelves and none of their competitors were, the Saturn would leap into a market lead, and then word-of-mouth would carry the console through the release of the PlayStation.

But for that idea to work, the Saturn would have to actually be on store shelves. And there, they ran into some deep problems.

Sega angered major American retailers

In the era before the internet, you had to go to a physical store to buy something. That meant big retail chains had a huge influence over which products would succeed or fail. Sega had in fact fought a protracted battle against Nintendo to gain favor with retailers during the Genesis era. Sega of America CEO Tom Kalinske didn't want to get on the bad side of any retailers, but his marching orders from Japan were to release the Saturn on the day of E3. That meant that only a paltry 30,000 units were available, and that in turn meant he couldn't stock every retailer with the console. In the end, he was forced to only allow four different chains — Software Etc, Babbages, Electronics Boutique, and Toys R Us — to carry the product at launch.

This led to a whole host of problems. Customers had trouble even finding a Sega Saturn in stock anywhere. Meanwhile, the company had shot its relationship with other major retail chains. Far from leaping into an early lead, the Saturn found itself starting on the back foot. Combined with the still-too-slim library of actual games to play, the Saturn simply didn't rack up any huge sales, or benefit from any solid word-of-mouth. That left the door open for Sony and its new PlayStation console to put the nail in the Saturn's coffin.

Sony avoided Sega's stumbles

While Sega was crashing through a series of mistakes, Sony was gearing up to break into the home console market with the PlayStation. At E3 1995, Sega made a splash by announcing the immediate release of the Saturn, but had also ruffled feathers with its expensive $399 price tag. And so, Sony retaliated with a splash of its own. When it came time to give its E3 presentation, Sony representative Steve Race simply walked onstage, said one number, and left. That number? "299." With only three digits, Sony announced the PlayStation would cost a hundred bucks less than Sega's console.

On top of that, Sony launched the PlayStation into all retailers at once, angering none of them. Even better, it had a good library of titles, both at launch and over the following years. Plus, it was a relatively simple hardware architecture to code for, as opposed to the much more complex, twin-CPU Saturn. All together, these factors led to a roaring start for the PlayStation, and a smashing success in the long run. Third-party developers largely abandoned the hapless Saturn for the new kid in town. Very quickly, the Saturn was simply left in the dust.

And after all that, the Saturn was less powerful than its rivals anyway

When all was said and done, the Sega Saturn was the least powerful of all the major players in the fifth-generation of consoles. The Sony PlayStation was also 32-bit, but much easier to program for with its simpler hardware architecture. For third-party developers, who weren't focused on the Saturn all the time, this made it much easier to create or port games to the PlayStation than Sega's machine. That, in turn, generated a deeper library for Sony.

And on the other side of the fence, Sega's first rival finally released the Nintendo 64 in 1996. Nintendo skipped the 32-bit era altogether, jumping straight from the 16-bit Super Nintendo to the new 64-bit console. Nintendo was so proud of this move, they even named the console after that glorious new 64-bit CPU. Though it still ran on cartridges, the N64 was instrumental in ushering in the new 3D era of gaming, with everything from platformers to first-person shooters.

The real shame here is that, once again, Sega might have been able to prevent Nintendo from getting their hands on that CPU in the first place. Silicon Graphics, a major chipset manufacturer, had actually approached Sega first about producing chips for the Sega Saturn. And once again, even though Sega of America was behind a partnership, Sega's headquarters in Japan shot the idea down. Silicon Graphics shrugged their collective shoulders and made the same offer to Nintendo instead. The result was the N64.

The Saturn's failure lead to the Dreamcast

As the fifth-generation of consoles drew to a close, the Japanese giant had been humbled. The Sega Saturn had been decimated by the success of the Nintendo 64 and especially the Sony PlayStation. Tom Kalinske, who had protested nearly every decision that Sega of Japan made regarding the Saturn, walked away as CEO of Sega of America. The situation was grim.

But the company rallied and decided to come roaring back into the sixth-generation of consoles. Once again, they would beat their rivals to the marketplace. And this time, they wouldn't be making the same mistakes. The new console, called the Dreamcast, was not only powerful, but finally brought a home console up to parity with what arcade machines could do. The Dreamcast also shipped standard with a modem, making it the very first console to feature online connectivity. For the launch itself, Sega spent $100 million on marketing, and ensured that there were plenty of both games and physical units to flood retailers – all retailers, equally. Plus, the launch date itself was September 9, 1999: 9/9/99. Try forgetting that one.

The Dreamcast today is still fondly remembered as one of the all-time great consoles ever made. And yet, it still wasn't enough. Sony's PlayStation 2 was simply more powerful, plus it could play DVDs and had better third-party support. After all the mistakes of the Saturn, the triumphs of the Dreamcast just weren't enough. Sega never released another console again.

So long, Sega

In the end, perhaps there wasn't any good way to compete with the original PlayStation, a magnificent machine in its own right. And maybe the Sega Saturn's 32-bit CPU would never be able to stand up to the Nintendo 64's chip. But really, the Saturn was the victim of a series of preventable mistakes that were largely foreseen by the company's own American division anyway.

If the company had waited a little longer to release the console, stocked every retailer with more physical units, and fostered better support for third-party developers, the Saturn might just have been a contender in the fifth-generation of consoles. As it is, it was a perfectly decent system that never broke out in the marketplace, and led to Sega's demise as a hardware manufacturer. What a gaming industry could look like if Sega were still making consoles, we can only wonder.