The Hidden Meaning Behind These Video Game Plots

While they can often be compelling, complicated, and ultimately rewarding, most video game plots are pretty straightforward. Save the princess, steal the cars, beat the boss, and occasionally alter human civilization forever. Even when there's a big twist, it's usually presented as part of the plot, changing everything about how you play the game after a big moment.

Every now and then, however, there are games that hide the true meanings of their plots just a little bit more than the others. It's not just limited to indie games, either — plenty of blockbuster titles from all different eras have a deeper meaning than you might expect. But now, we're blowing the lid off the hidden meanings behind these video game plots.

Mega Man: The true evil of Albert Einstein

Of all the games on this list, Capcom's Mega Man series definitely seems like the most straightforward. You move through the levels, beat each Robot Master, then take on the evil Dr. Wily in the climax. The only complication is figuring out the proper order that will allow you to exploit each boss's weakness, right? Look a little deeper, though, and it becomes a little more complicated.

Surprisingly, this has nothing to do with Mega Man himself. Instead, it has to do with the human scientists in the games — and the real-life figures that seem to have inspired them. Dr. Thomas Light is pretty obviously named for Thomas Edison, famous for inventing the light bulb. His opposite number, on the other hand, is only really obvious if you dive into the manual and check out his first name.

With his wild hair and mustache, Dr. Albert Wily bears more than a little resemblance to his real-world counterpart, Albert Einstein, especially in his original NES sprite. Considering that he might just be the most well-known and respected scientist of all time — to the point where most people just use his name as a slang term for "genius" — it might be surprising that a megalomaniacal villain bent on world domination would be based on Einstein. Until, that is, you remember that Einstein is also known for his work on the Manhattan Project, which resulted in the invention of the atomic bomb.

His tie to nuclear weapons, which would proliferate to the point of having the capability to literally destroy the world, gives him a unique connection to the dark side of technology, and the danger that can come even from things that were thought up for peaceful purposes. You know, like the Robot Masters that have turned evil in the game.

Admittedly, the game character diverged pretty hard from his inspiration — Wily's look became markedly different as the games evolved, and Einstein did not, in fact, live in a series of giant skull-shaped castles. But the connection seems to be there in a way that it isn't for Dr. Light. Unless they spend some time in the next game having him electrocute an elephant, that is.

Mass Effect 3: The cosmic do-over

The much debated ending of Mass Effect 3 features a narrative choice, but in all of the choices, the Mass Relays that have provided travel around the galaxy get destroyed or damaged — and this isolates societies until they can figure out how to rebuild the relays. As we see in the above final cutscene with the Stargazer (voiced by astronaut Buzz Aldrin), humans are working on fixing them sometime in the distant future. It's a surprisingly uplifting ending that brings humanity's relationship with the rest of the galaxy full circle, and for all of its flaws, it makes for a satisfying conclusion to the Mass Effect mythos. So what's the hidden meaning here? The ending is even more of a rewarding, feel-good moment if you've been paying really close attention.

The game doesn't just hand this meaning to you: You'd have to be the kind of person who obsesses over the details and lore presented in the completely optional in-game codex to dig this out. See, one of the biggest events in the Mass Effect canon was the brief but bitter First Contact War between humans and the Turians. In other words, Earth's first encounter with an alien race was aggressive and violent, setting the tone for humanity's relationship with the rest of the galaxy, which is why the aliens were so suspicious of humans all the time. But this ending shows humans working toward a much more peaceful second chance at reconnecting the universe and meeting those alien races as friends and allies. Now that the humans remember how badly things went the first time around, this second shot seems destined for love, not war. Let's just hope all the aliens feel the same way when the humans make second contact.

Castlevania: It's just a movie, kid

Since its 1986 debut on the NES, the Castlevania franchise has expanded and evolved into an incredibly complex saga with a deep (and occasionally nonsensical) storyline. Over the course of dozens of games, players have been told about the intertwined destiny of Dracula and the Belmont bloodline, and the curses and triumphs that have defined their existence for a thousand years.

It makes sense that things would get pretty complex, too, because those games have an awful lot of weird stuff to explain — including how Dracula got to be in charge of all the other monsters and why this family thinks that the best way to deal with this unstoppable force is to hit it with a whip. But while the stories of cruel fate and sacrifice have made for some interesting games, there's a much simpler explanation that's given to us right at the start of the very first game: it's just a movie.

That's the big trick behind the original Castlevania, and why the opening resembles a film strip — and why the ending features movie-style credits with parody actor names. It's not actually meant to be some vast, gothic saga, it's just a crossover where you're fighting against all the famous monsters from the Universal films — like the Mummy, Frankenstein, and, of course, Dracula — with Clash of the Titans' Medusa thrown in for good measure. Even Simon Belmont himself is a movie mashup of Conan's look and a weapon lifted from Indiana Jones. If you missed it in the original game, the opening of Castlevania II: Simon's Quest (above) and Castlevania III: Dracula's Curse put the film strip in motion to make it a little harder to ignore.

It's not until the series moved to the SNES that they thought that it might be time to give the series its own distinct mythology. That might seem a little dismissive given the work later put into the plot, but let's be real: it's better than the origin story we got in Lords of Shadow.

Altered Beast: Rise from your stage!

Plenty of video games like to frame themselves as different kinds of stories. Castlevania starts with the film roll of a movie, Super Mario Bros. 3 opens with the curtain going up on a stage, and the relatively obscure Rockin' Kats divides its levels into television channels to give the impression that you're watching a show.

The thing is, even if it's just a quick bit in the intro, all of those games are pretty up front with what they're doing. Altered Beast, on the other hand, hides its plot twist until the very end. After you famously "rrrrise from your grrrave" and brawl your way through five levels of vaguely Ancient Greek monsters, you're rewarded with the end credits... which reveal that the whole thing was fake. Like, faker than usual.

As the credits roll, players are treated with some still images from crucial moments of the game, followed by "behind the scenes" shots of the characters hanging out on the set — including ones where the monsters take off their costumes and share a wrap party beer with the protagonists. Who knew you were just wailing on stuntmen all that time?

Twisted Metal Black: It's all in your (flaming) head

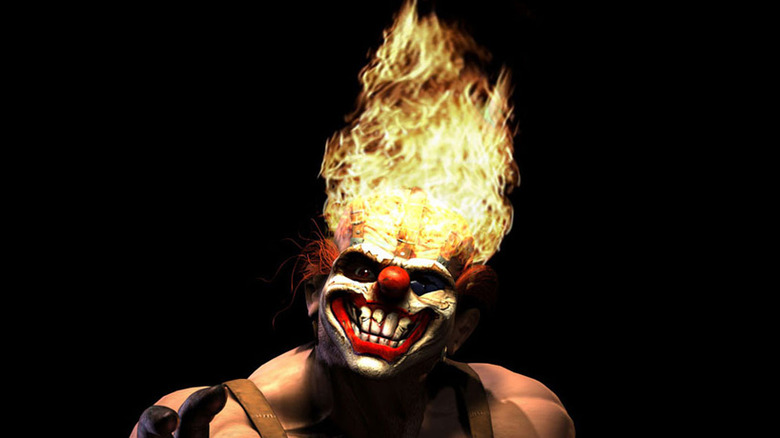

The Twisted Metal series, made up of vehicular combat games about modified cars in a battle to the death, was never exactly wholesome entertainment. With 2001's Twisted Metal Black, though, Incognito Entertainment took the series in an incredibly grim direction, which is saying a lot since the mascot of the franchise was already Needles Kane, a serial killer clown with his head permanently set on fire by demonic forces.

Rather than being set in a near-future Los Angeles with competitors from all over the world, Black's Twisted Metal tournament drew its cast from the inmates of Blackfield Asylum, including killers, cannibals, and, in one case, a woman who had her face permanently encased in a porcelain doll's mask in order to disfigure her features. It's dark stuff, but it gets even darker at the end of each character's storyline, where their wishes are granted with either more brutal bloodshed, or the kind of Monkey's Paw irony that makes them truly regrettable. But while each story takes its own share of turns, there's one final twist to the metal that requires a whole lot of effort to uncover.

Once you beat the game with every other character — including the secret ones that you unlock during the game — you'll get access to Minion, an armored big-rig that serves as a mid-game boss. Play through as him, and you'll notice that unlike the others, he doesn't have dialogue on the loading screens, just sequences of numbers. Each number, of course, corresponds to a letter, and if you take the time to decode them, you'll find that Minion's driver believes that everything that's happening in the game is taking place inside Sweet Tooth's mind.

The kicker? It's also revealed that Minion is Marcus Kane, who is not only Needles' alter ego, but the character in Twisted Metal 2 who speaks directly to the player and knows that it's all a video game. Either way, the fact that the game world is created within the disturbed mind of a murder clown goes a long way towards explaining why it's so dark, and why the people who get the worst endings are authority figures.

Saints Row IV: Video games are a prison

The Saints Row franchise has never been afraid to get a little meta. Saints Row III, after all, opens with a scene where the player puts on an oversized mascot costume of one of the Saints and is then immediately thrown into the most cartoonish heist of all time, which involves stealing an entire bank vault and then jumping out of and back into an airplane in mid flight. With Saints Row IV, however, things hit a little closer to home.

The plot involves an alien overlord named Zinyak, who descends on Earth, blows it up, and takes you and your crew of criminals-turned-celebrities hostage. Then, to imprison you, he puts you and all the other survivors of Earth into a virtual prison. A prison that just happens to be a slightly modified version of... Saints Row III.

Maybe we're reading too much into this one — especially since SRIV got its start as a VR-themed DLC pack for SR3 called "Enter the Dominatrix" that was later released with in-character commentary — but given how Zinyak is one of the few open-world crime simulator characters to actually call you on being humanity's greatest monster, the idea of building a video game with a hidden meaning about how video games are a prison that separates you from reality isn't that unthinkable.

Mario: why a plumber is the perfect hero

If you have even a passing interest in the history of video games, then you likely already know that Mario got his start as "Jumpman," the protagonist of Shigeru Miyamoto's Donkey Kong. Eventually, he'd go on to be one of gaming's iconic characters. But while he's found success in tennis, go-kart racing, soccer, partying, princess-rescuing, and occasionally being made of paper, he's been referred to consistently as a plumber by trade ever since the early days.

The reason here is simple: after Donkey Kong, his next breakout hit was the original arcade Mario Bros., which used sewer pipes as a way to explain where all the enemies came from. When that game was expanded into Super Mario Bros., arguably the most influential video game of all time, the pipe motif stuck. This time, though, they were different — they appeared as part of the landscape, leading not to sewers, but to underground caves. By Super Mario Bros. 3, there was even an entire country built out of those famous green pipes, as you can see in the video above.

So while Mario has been changing careers ever since he started climbing up skyscrapers with a hammer, his experience with pipes and plumbing was the one that came to define him — and not just because it's the kind of profession that makes him an everyman hero and gives a little fun to his fantasy-world exploits.

In the Mushroom Kingdom, pipes seem to either be naturally occurring geographical features or the last ruins of some ancient society that Peach and the Toads have built their new homeland on. Either way, the Warp Zones prove that pipes have some strange mystical properties, so in that world, a "plumber" isn't just someone you call when your kitchen is ankle-deep in water.

The Toads would see someone who had the ability to manipulate and connect pipes as something more like a mystical wizard, in the same way that we'd see someone who could, say, effortlessly travel from one mountain to the next in an instant, as a pretty impressive warrior. You even have to go through pipes to reach Bowser's castle! In that respect Mario's expertise with pipes means that he's anything but an "everyman" in the Mushroom Kingdom — he's actually the perfect hero for this very strange world.

The World Ends With You: Stop playing so many video games!

With its innovative control scheme and mechanics based on following Japanese fashion trends, The World Ends With You was a surprise hit — especially surprising when you consider that it's a game all about how you should probably stop playing video games.

In the game, you play as Neku, an anti-social loner who has a lot of trouble making friends, and who finds himself trapped in a shadowy version of Tokyo's Shibuya district, thrown into a series of games and challenges put on by a group of powerful opponents called Reapers, who serve as the controllers of your gamified afterlife. Over the course of the game, you find out that most of the winners who chose to move on actually elect to become Reapers themselves rather than moving on to a final reward. In other words, the people who are good at the game just keep on playing the game, and your goal as Neku is to escape that cycle and stop playing.

The message of the story is about the value of getting out in the world and making friends, but the gameplay backs that up. One of the most memorable aspects of the combat is that you're asked to control two different fights with two separate methods of input — the touchscreen for Neku and various button-based controls, including literally doing math, for his companion — but you're also given the choice to set your companions to fight automatically without your control. On top of that, certain items even gain experience and grow more powerful only when you're not playing. Put it all together, and it's a game that wants you to go do something else with your life... at least for a little while.

Tony Hawk's Underground: Soul vs. sellout

Despite a rather unfortunate revival in 2015, the Tony Hawk's Pro Skater franchise ruled extreme sports games for a decade. In 2003, Neversoft and Activision evolved the franchise by adding something that went beyond just new tricks or more ridiculous rails to grind: a narrative. The game follows a player-created character as you rise up from street skating in your local neighborhood to corporate sponsorship, and all the way back to finding the true meaning of skating within your own soul.

Through the story, you have to deal with your hometown rival, Eric, as he steals your accomplishments, sabotages your competitions, and even frames you for crimes, all in the name of getting a big sponsorship and staying a pro tour. The thing is, the conflict between sponsorships and the true meaning of skating is one that can hit pretty close to home for Hawk himself, who was, and is, the most famous name in skateboarding, as evidenced by the fact that you were playing the fifth major video game with his name in the title.

But with that fame came criticisms that Hawk was a sellout who only cared about getting corporate money, who didn't care about really skating on the street. By lending his name and image to a game that was about rejecting sponsorship if it meant compromising your morals and devoting yourself to the sport, Hawk was able to indirectly answer his critics — and, incidentally, make a ton of money in the process. As Hawk says himself, "you only get called a sellout when people buy your stuff."

Oregon Trail: The world doesn't need more bankers

The original Oregon Trail holds a special place in the heart of '90s kids everywhere: it was the one video game that you were always allowed to play in school. The reason, of course, was that it was nominally educational, representing the actual journey from Missouri to the Oregon territory undertaken by settlers in the 1840s, complete with historical landmarks. Throw that educational content with the action-oriented scenes of hunting for food and the unintentional comedy of watching characters named after friends (and enemies) dying of 8-bit dysentery, and you've got a recipe for a memorable game.

But there's one hidden message that you might not have noticed in your hurry to see if a family member named FARTS drowned while trying to ford a river: the professions you choose at the beginning of the game are actually a stealth difficulty setting. Picking a banker, carpenter, or farmer doesn't just change the amount of money you get before you set out on your journey; it determines a bonus to your score once you make it to Oregon. A banker gets nothing, while a farmer's base score is tripled.

The hidden meaning here is pretty clear. Life's a whole lot easier if you have money, but at the end of the day (and at the end of the game), the contributions of a carpenter or a farmer are going to be a lot more valuable in building a new place to live. About three times more valuable, in fact.