What God Of War Looks Like Without Special Effects

Video games have come a long way since their spritely beginnings. Not only have graphics improved, but developers have breathed new life into larger-scale projects with rich stories and award-winning voice acting. Every year, the gulf separating video games and real life seems to shrink, and studios have sped up that process with an evolving library of tricks and techniques. To see this in action, look no further than "God of War."

The "God of War" franchise has been around for almost two decades. The first entry released on the PlayStation 2, and while the game looked fantastic for its time, it was developed using then-modern technology, which is now quaint by modern standards. The initial "God of War" games were built with programs such as Maya and felt larger than life. But when "God of War" was soft-rebooted for a new console generation, its developers had to revise their process.

To realize the studio's new vision, Sony's Santa Monica Studio reinvented the wheels that make the "God of War" machine run. As a result, the development of "God of War," and by extension its sequel "God of War: Ragnarok," became a more involved beast. But going by review scores, the process was worth it.

What else goes into a game?

What is more important in video games: graphical fidelity or art design? Trick question. The correct answer is a talented concept artist and a team of developers who can bring its drawings to life.

As with all video games, "God of War" and "Ragnarok" started with ideas. The narrative teams invented characters, monsters, and other entities and determined their niches, both in terms of combat and their homes within levels. The concept artists then translated these ideas into images and blasted through countless iterations before settling on the final designs. One example of this process is Kratos himself. During the first "God of War" game's development, concept artist Charlie Wen went through numerous drawings before he created the bald, tattooed Spartan warrior we all know and love. And when it came time to reboot the series for 2018's entry, Kratos went through a similar process. Early concept art toyed around with keeping his iconic goateed look, albeit with more realistic proportions, while his signature Leviathan Axe was originally envisioned as a more mundane weapon.

Once concept art was finalized, a separate team of modelers translated the art into 3D assets. This process was more straightforward as all the kinks had been ironed out, and designers streamlined their work even further with some palette swaps (tweaking an existing model to create a new asset). Sometimes deviations were necessary, though. For instance, concept art of Sindri made him look a little...bug eyed. This design was toned down for the final product.

The line between live and virtual blurs

The cutscenes in the "God of War" soft reboot feel far more lively than prior "God of War" games. Characters offer a wide range of emotions, especially Kratos, who has moved beyond his previously permanent scowl. How did the developers at Santa Monica manage this? By using live people.

In order to create the majority of cutscenes and animations in "God of War," staff used a method called "previsualization," or "previs" for short. This process primarily consisted of planning out where characters would stand in a scene, acting them out live, and filming the results. The videos can feel a bit comical, since previs shots rarely involved trained actors — and because everyone who stood in for the dwarves Brok and Sindri waddled around on their knees to approximate the characters' heights. However, this previs filming was never meant to look good; it was meant to test out different camera angles, get timing down, and quickly revise and reshoot until staff got it right.

While live previs had its uses, sometimes developers had to previs with basic game models. Whenever the team needed to get a proper sense of scale or understand how models would interact with each other, they relied on digital previs shoots. Instead of relying on random staff members, developers used rough, untextured models with janky and unfinished animations. These previs tests provided the same results — just with fewer people waddling on their knees.

Happy AXE-idents

The majority of Kratos' moveset was mocapped by stuntman Eric Jacobus, who brought life and brutality to every punch and axe swing. But unlike Kratos, Jacobus is just a man and is restricted by reality. Some of Kratos' more fantastical attacks were only made possible by the imagination of Santa Monica staff.

During a GDC 2019 panel, Lead Gameplay Designer Jason McDonald discussed how the team gave Kratos his axe-based attacks. According to McDonald, animators pitched ideas to expand Kratos' moveset by creating digital previs animations. The most notable pitch was designed by Lead Animator Mehdi Yssef. His video consisted of a short animatic with basic, if visceral, combat. McDonald loved the concept, but one aspect stuck out: During the previs fight, the stand-in for Kratos threw its axe at an enemy.

McDonald was initially concerned and confused by this move. Kratos' axe was supposed to be the then-upcoming game's central weapon. What would happen if players never retrieved the axe after throwing it? This fear convinced McDonald to initially dismiss Yssef's proposal, but then Lead Systems Designer Vince Napoli suggested adding the power to recall the axe with the press of a button — not unlike, in McDonald's words, "a certain Norse god." Programmer then George Mawle developed prototypes of Napoli's idea, and a key ability for the Leviathan Axe was born.

Sometimes the best game design ideas are only possible after stepping back and looking at them with extra eyes.

Props to the prop department

Creating animations and cutscenes with live people isn't as easy as strapping on a mocap suit and yelling, "Action!" If a character is supposed to swing an axe, their actor can't just flail their arms around. A little bit of heft goes a long way. As with games such as "Apex Legends," the animation team for "God of War" used a ton of props for both mocapping and live previs.

Some props were easy to source. Kratos' axe, for instance, swapped between a Nerf mace and a foam axe, while Sindri's apple was portrayed by...an apple. But sometimes the team had to get a little more creative. How do you represent Kratos' iconic (but unrealistic) Blades of Chaos? With foam rubber pool noodles, of course. The same creative logic applied to Kratos and Atreus' canoe. Instead of lugging a real one into the mocap set, the team created mechanical rigs that could be used for different scenes, such as Kratos pulling the boat or being tossed around by rough waters.

Not all props from "God of War" were traditional. Some, such as beanbags, were crucial for cushioning blows whenever mocappers had to simulate grapples. One prop stood out from the rest, though: To help developers nail the scale of ogres while creating live previs shoots, the team built a giant "suit" made out of a deconstructed cardboard box and printed the ogre's face on top where the head would be. It was silly, but it got the job done.

The magic of MotionBuilder

Developers have no shortage of programs for modeling and animating. Some popular choices include Blender, ZBrush, and Houdini. Older "God of War" games used Maya, but for the soft reboot, Santa Monica Studio turned to MotionBuilder.

This program is a motion capture and keyframe animation suite produced by Autodesk. One of MotionBuilder's many features includes the Virtual Camera, which acts just like a regular camera but transposes every actor wearing a mocap suit it sees into the game world. Santa Monica Studio leaned heavily on this feature to give cutscenes a handheld camera documentary feel, mostly because they were filmed by a stagehand holding a camera running the program.

Because MotionBuilder essentially filmed digital environments, it streamlined the process far more than normal cameras. Santa Monica filmed Kratos and Atreus' actors – Christopher Judge and Sunny Suljic - reacting to Jormungandr, while also inserting a representation of the giant serpent into the scene with some puppeteered dots.

MotionBuilder also let one actor play multiple roles, such as during the escape from Hel scene, where Kratos sees a ghostly vision of himself killing Zeus. In normal mediums, this scene would only be possible with two actors, one for each version of Kratos. MotionBuilder, however, recorded the stunt actor punching Zeus to death, saved that data in the digital landscape, and inserted it seamlessly into another recording of the same actor observing the phantasmal carnage.

It's Always Sunny in Midgard

The beauty of motion capture is that virtually any actor can play any character. You'd be surprised how many animals in movies were created using humans in mocap suits. However, sometimes there's no replacement for a genuine performance from an actor of the right height and build. In "God of War," Kratos and Atreus were portrayed by Christopher Judge and Sunny Suljic, respectively. Not only did they provide the voices, but they also were responsible for much of the motion capture. Stunt actors replaced them for certain scenes, but Suljic was far more crucial to mocapping than most probably realize.

Atreus sounds like a young kid in "God of War" because his actor, Suljic, was a young kid at the time of filming/recording. According to The Hollywood Reporter, Suljic was around 10 years old when "God of War" was in development. This age gave him a leg up in vocal performances and mocapping. Because Judge is 6'3" (one inch shorter than Kratos in the game), Suljic looks tiny next to him, which in turn made the cleanup process smoother. Plus, Suljic's mocapped movements gave Atreus the perfect childlike energy because, well, he was a child when he wore the suit in the first game.

Mocap isn't the only option

Motion capture provides the lion's share of work for animators, but sometimes (or often) it needs a little help, especially when designers want characters to ignore physics. After all, the "God of War" franchise is built on such moments.

Whenever the team at Santa Monica Studio wanted to create a scene it couldn't physically shoot via mocap or even previs, the team relied on traditional animation techniques. One example of such a moment includes when Kratos and Atreus fall off a cliff. To develop this scene, animators built it using simple, untextured models and moved them around by hand. Animals and other inhuman monsters were also animated one frame at a time since they were impossible to mocap — Jormungandr and Freya's turtle house, especially.

Even when developers were able to capture mocap performances, they often had to supplement the results with hand-built edits. Sometimes the animators only needed to stitch animations together to produce large scenes and environments, while other times they tweaked models to account for changes in environments and timing that occurred after recording. Sometimes, edits were necessary to make mocapped animations look cooler. For instance, the Blades of Chaos were expanded with many edits since they follow video game logic. In order to make them look powerful, animators improved mocap data to give each swing a little more "oomph."

Accounting for player choice

Throughout Kratos' adventure, players can find, buy, and equip different pieces of armor and weapon pommels. Not only does each item provide different stat boosts, they also sport their own models. Some armor pieces include large pauldrons, while others don't, and some pommels are so long they look like Kratos duct taped a dagger to his axe. Players can equip virtually any one of these items at any time, which can result in clipping during cutscenes if animators don't compensate.

To prevent some nastier clipping issues, designers rigged up a few clever workarounds, the most notable of which is demonstrated during the cutscene in which Kratos pulls the canoe. He tugs at the boat with a rope over his shoulder, but during development, depending on what Kratos wore, the rope would either phase through armor or hover above it. To solve this digital physics nightmare, the art team created four different ropes with their own joints, meshes, and heights. Then, the integration team programmed the ropes to becoming visible depending on the armor Kratos equipped at the time. Technically, all four are present during the finished cutscene; three are invisible, and the game determines which one players see by examining the size of Kratos' armor.

Few clipping issues were as nasty as this rope during development. Usually, developers could "fix" armor issues by altering the camera. Players can't tell a piece of armor is clipping if they can't see it. Other times, tweaking animations would provide the solution. But as the rope demonstrated, sometimes the only solution is a bit of "if/then" coding magic.

An invisible guide hiding in plain sight

Level design is an artform all its own. Designers have to create areas that are believable and beautiful, but they also have to follow a strict set of game logic criteria without revealing them to the audience. That is a tightrope walk.

During a 2019 GDC panel, the lead level designer of "God of War," Rob Davis, discussed what he called the "core pillars" of level design for the game and how he implemented them into locations. Davis argued that proper level design boils down to metrics that emphasize these pillars. In order to streamline the process, Santa Monica Studio staff followed a "building codes document."

According to Davis, the world of "God of War" consistently follows this important document. For example, every surface that players can jump up to is, at its core, a 2.4 meter-wide rectangle with heights that range from 1 to 3 meters in 1 meter intervals. Debris and vegetation might disguise their shapes, but each ledge in the game follows this design philosophy, whether you realize it or not.

"God of War" environments are admittedly far more complicated than tiny cliffs that players can scale. The game includes crawl spaces, low ceilings, and rock climbing segments, but even these follow the same basic principles and designs as all the others of their type. The game masterfully melds these gamified sections with organic architecture, and few players probably noticed.

Battles are a jigsaw puzzle of mechanics

When players praise enemies in video games, they usually mention their "AI". The Xenomorph in "Alien Isolation," for instance, is hailed as a landmark in insidious AI design that doesn't stick to predictable behaviors. In reality, all enemies in video games stick to patterns, and what we consider "AI" is actually an orchestra of systems working together.

In "God of War," all enemies are controlled by an aggression system. During combat, each monster is assigned a token that determines whether it will be aggressive. Enemies with aggression tokens attack players (obviously), while others hang back, but the system is more complicated than a binary metric. The system weighs numerous criteria, such as how close a monster is to Kratos and if they are on camera. The system then scores them on the results and assigns them tokens based on these scores. These tokens constantly refresh to keep fights dynamic. This mechanic also puppeteers enemy placement; non-aggressive enemies clump together, but aggressive enemies give each other a wide berth so they don't crowd players.

Atreus and the player also have their own AI systems. Atreus', for example, tells him when to stand his ground and when to flank opponents. Atreus also utilizes a warping mechanic that lets him teleport while off camera to enter Kratos' line of sight faster. Players, meanwhile, receive a grab bag of under-the-hood mechanics. The game intelligently "sucks" players closer to enemies to make hitting them easier and caps the height enemies fly while juggled. "God of War" even autonomously keeps enemies on screen as much as possible with "strafe assist" and "strike assist" systems. The less players have to finagle the camera, the more they can focus on proper dodging in intense combat situations.

Back when Kratos killed Kratos

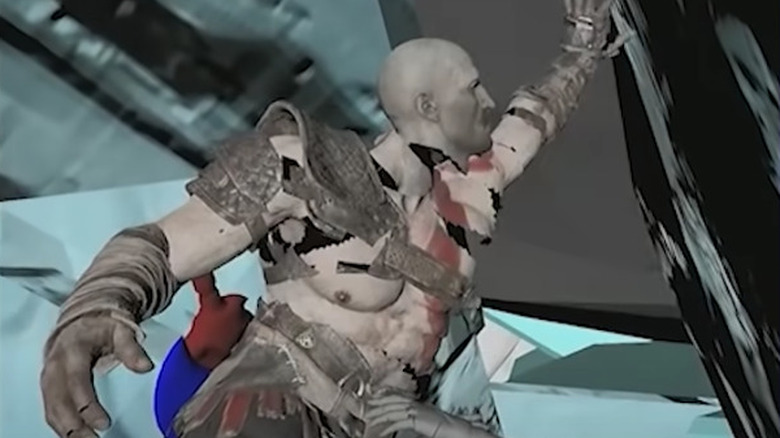

Early animations can be rough. Usually, developers create this data before they've finalized models, which means they have to use whatever assets they have on hand or can drum up in a pinch. This helps to show off their vision, but it can also lead to unintentional comedy.

When Santa Monica Studio developed early ideas for 2018's "God of War," the developers wanted to create combat that was much more grounded. Magic wasn't part of the vision just yet, so the team tested ideas with two models. One was a basic, untextured hatchet, while the other was Kratos. In order to demonstrate what they had in mind, animators needed Kratos to kill someone. Instead of taking the time to create a third model, the animators just recycled what they already had.

In these early proofs, rough models of Kratos attack and kill copies of himself. The developers used these admittedly hilarious clips to gauge their vision and see if they were on the right track or if they were missing anything. As history has shown, Santa Monica employees concluded that the clips were missing the "God of War" magic (literally), so they iterated on them. As the movesets evolved, so did the models they used. Eventually, animators let Kratos kill more than just clones in these tests, as well as spin his axe around like a boomerang.

Kratos might still be full of self-loathing, but at least he's not mowing down copies of himself anymore.