Video Game Legends You May Not Know Are Dead

The video game industry is still young, and many of its original innovators are still around. That's good news, because we're not ready to say goodbye to the likes of Shigeru Miyamoto, Nolan Bushnell, Will Wright, or Sid Meier just yet.

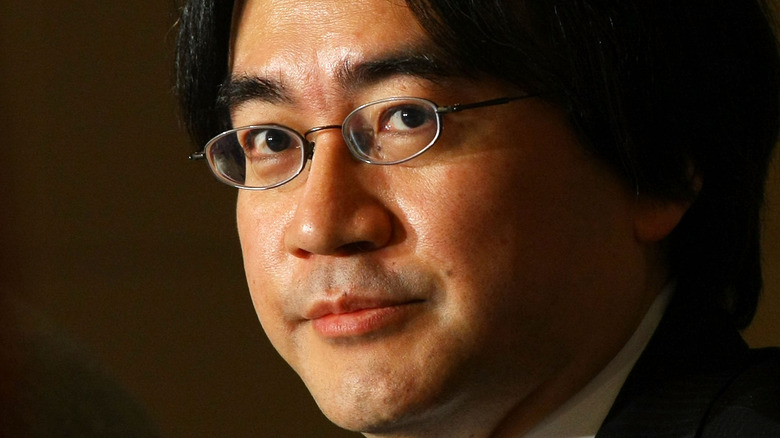

But not everyone is so lucky. In 2015, video game fans said goodbye to beloved Nintendo president Satoru Iwata (pictured above), and that's just the tip of the iceberg. Some of video gaming's biggest pioneers are no longer with us. Whether they succumbed to old age, illness, or were taken from us before their time, each one of the following developers, designers, athletes, and journalists had a profound impact on the video game industry. While their time on Earth might have ended, their contributions to gaming will never be forgotten.

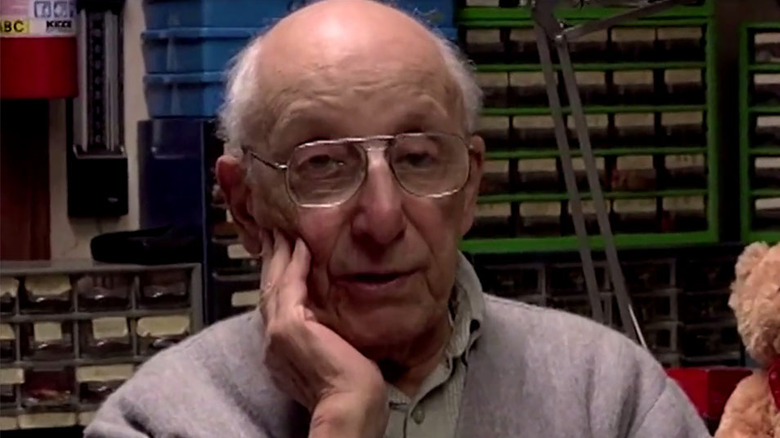

William Higinbotham, the first game developer

In 1958, 14 years before Pong propelled video games into the mainstream, physicist William Higinbotham created Tennis for Two, which is widely (and legally) considered the very first video game ever made. Unlike other contenders for the throne, Tennis for Two takes place entirely on an animated digital display (the Cathode-Ray Tube Amusement Device, which predates Tennis for Two by 10 years, relied on overlays placed on top of the screen, the digital adaptation of Nim used lights instead of a screen, and the Tic-Tac-Toe simulator OXO didn't have moving graphics). Further, Tennis for Two wasn't made as a tech demo or a scholarly experiment. Higinbotham simply made the game because he thought it would be fun.

He probably needed a break, too, because Higinbotham's day job involved working in Los Alamos, New Mexico alongside the team that created the first atomic bomb, developing electronic radar displays for various aircraft, and helping to establish the Federation of American Scientists, an organization dedicated to nuclear disarmament. Compared to all that, Tennis for Two is a trifle. And yet Tennis for Two, which Higinbotham designed in two hours and programmed in about two weeks, still paved the way for an entire multi-billion industry.

Not that Higinbotham got any of that money, of course. While Higinbotham owned more than 20 patents, he didn't get protection for Tennis for Two, claiming that he "didn't think it was worth it." Instead, Higinbotham worked for 47 years at the Brookhaven National Laboratory on Long Island, and after retiring served as a consultant to the lab until he died of emphysema in 1994.

Ralph Baer, the father of video games

Ralph Baer accomplished a lot in his 92 years on the planet. In 1938, he fled Nazi Germany with his family, ultimately settling in the United States. In 1943, he was drafted into the United States Army, where he worked in Military Intelligence and wrote training manuals for D-Day soldiers. After the war ended, he received one of the first-ever degrees in television engineering, and he worked at the defense contracting firm Sanders Associates from 1956 through 1987.

But Baer will always be best known as the creator of the Magnavox Odyssey, the first home video game console and an invention almost 20 years in the making. In 1955, Baer's bosses at Loral Electronics Corporation tasked him with "building the best television set ever." Baer had an even better idea: what about a TV set that played games? His bosses said no, but Baer didn't give up. 11 years later, Baer and a colleague prototyped the so-called Brown Box, which played a handful of games (including the Pong-like Table Tennis). A few years later, Magnavox licensed the device, released it as the Odyssey, and console gaming was born.

Copycats quickly emerged but, unlike Higinbotham, Baer and Magnavox had the foresight to patent the Odyssey and its games. Atari settled for $700,000 and a licensing deal after Pong ran afoul of the Odyssey's patent, and over the years Magnavox collected $100 million in Odyssey-related lawsuits. That's how widespread the Odyssey's influence was. Console gaming isn't the only thing that Baer invented, of course—before he died in 2014, Baer created everything from talking door mats to the memory game Simon. But it's in devices like the Xbox One, PlayStation 4, and Nintendo Switch that Baer's legacy truly lives on.

Masaya Nakamura, the father of Pac-Man

While Nakamura is commonly called "the father of Pac-Man," he didn't actually make the game. That honor belongs to Toru Iwatani, who (as of this writing) is still alive and kicking.

But Masaya Nakamura did found Namco, the company that employed Iwatani, and helped guide it into becoming one of the most influential video game developers of all time. Nakamura started Nakamura Manufacturing in 1955 after installing two mechanical horses on top of a Japanese department store, where they were designed to keep children entertained while their parents shopped. The rides were moderately successful, and for the next 20 years or so Nakamura Manufacturing created kiddie attractions at malls and department stores across the country.

In the '70s, however, Nakamura realized that video games had the potential to be big business. He changed the name of his company to Nakamura Amusement Machine Manufacturing Company (or NAMMCo!, later shortened to Namco), produced a projection-based arcade game called Namco F-1, outbid Sega to buy Atari's struggling Japanese affiliate, and started stocking up on talent to produce games. Galaxian, a Space Invaders riff, was one of Namco's first big hits, but it was nothing compared to Pac-Man, which went on to become the highest-earning arcade game ever.

Nakamura didn't expect Pac-Man to be quite so popular. "I knew it would not be a single. But I thought maybe a double, not a home run," he told an interviewer in 1983. But it was, and helped establish the still-flourishing Japanese game industry in the process. For his efforts, Japan honored Nakamura with the prestigious Order of the Rising Sun in 2008. Nakamura died almost a decade later, in January, 2017.

Hiroshi Yamauchi, the man who reinvented Nintendo

Nintendo didn't always make video games. When the company was founded in 1889, it made playing cards. Their licensing deal with Disney helped expand Japan's playing card market, while Nintendo's line of durable Western-style cards, which had been previously associated with gambling, helped Nintendo dominate the industry. But Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi had loftier ambitions for Nintendo, and during his 53-year reign, he transformed it from a regional card company into something much bigger.

In 1949, Yamauchi dropped out of college to take over Nintendo from his ailing grandfather, on the condition that he'd be the only Yamauchi family member working for the company (the demand cost Yamauchi's cousin his job). When the playing card market stalled in the '60s, Yamauchi started exploring other business opportunities, including light gun-based arcade attractions, "love hotels," packages of noodles, and pitching machines, before settling on video games.

Nintendo's first home console, the Color TV Game 6, launched in the '70s, but Nintendo didn't become a household name until Shigeru Miyamoto's Donkey Kong took arcades by storm in 1981. Suddenly, Nintendo was everywhere, and Yamauchi oversaw the company as it cycled through the Nintendo Entertainment System, Game Boy, Super NES, Nintendo 64, and Game Cube. He retired in 2002. Not a bad legacy for someone who, according to reports, didn't like or understand games. Yamauchi succumbed to pneumonia in 2013, but by then, his work was done. Nintendo, and the world, would never be the same.

Danielle Bunten Berry, the woman behind M.U.L.E.

Don't let the primitive graphics fool you. If you can get it working, M.U.L.E. is still one of the greatest multiplayer video games of all time. In M.U.L.E., four players battle it out on the fictional planet Irata in order to secure resources, wealth, and their colonies' long-term survival. It's part Monopoly, part economic simulator, and part auction house, with an overall aesthetic inspired by Robert A. Heinlein's science fiction novels and The Empire Strikes Back. Well-known designers like Will Wright and Sid Meier cite M.U.L.E. as one of their favorite games. And while it's complicated, it's a heck of a lot of fun.

It was all the brainchild of Danielle Berry, who was asked to create the game after Electronic Arts founder Trip Hawkins failed to secure the rights to one of Berry's earlier games, Cartels & Cutthroats. M.U.L.E. didn't sell particularly well—allegedly, EA only moved 30,000 units—but it was widely pirated and influenced a whole generation of strategy game designers. Berry went on to create Modem Wars, the first PC game that could be played online across multiple machines, and remained a vocal advocate for multiplayer games until she died of lung cancer in 1998.

Berry broke barriers in other ways, too. She was one of the first openly transgender women in the game industry, and was eventually honored for her contributions with a lifetime achievement award from the Computer Game Developers Association and a posthumous induction into the Academy of Interactive Arts & Sciences Hall of Fame. When The Sims debuted in 2000, developer Will Wright dedicated the game to her memory.

Bill Kunkel, the grandfather of game journalism

You might not know Bill Kunkel's name, but if you're reading this, you're certainly familiar with his work. In the '70s, Kunkel and his partner, Arnie Katz, created Video Magazine's "Arcade Alley," a column that documented the current happenings in the video arcade scene. In late 1981, the duo launched Electronic Games, the first American magazine devoted to video games. After serving as editor-in-chief of Electronic Games for a number of years, Kunkel began contributing to other game magazines, writing columns like "The Game Doctor" and "The Kunkel Report."

That's not all that Kunkel accomplished. In the '70s, he worked with various comic book companies, scripting series like House of Mystery, Action Comics, and Marvel Team-Up. He worked as a pro-wrestling journalist, contributing photographs to Main Event Magazine and columns to Pro Wrestling Torch and Wrestling Perspective. Kunkel also taught game design at the University of Nevada Las Vegas, and helped design one of the first pro wrestling video games, MicroLeague Wrestling. He even testified as a video game expert at various copyright-related trials.

But Kunkel will always be best known for creating the field of video game journalism. Many of the terms the gaming press use today—screenshot, mechanics, and Easter egg, among others—were coined by Kunkel and the Electronic Games' staff. As a columnist, Kunkel was famous for his insightful views on both game design and the industry as a whole. Kunkel suffered a heart attack and passed away in 2011, but his legacy lives on in the Society of Professional Journalists' Kunkel Awards, which honor the best video game journalism of the year, as well as every single video game news site on the internet.

Dennis Hawelka, the INTERNETHULK

Overwatch is only a few years old, and yet it's already lost one of its biggest stars. Dennis Hawelka, better known to fans as INTERNETHULK, passed away in late 2017 at the age of 30, leaving behind a devastated family and legions of mourning fans.

Hawelka first entered the esports scene through Blizzard games like World of Warcraft and StarCraft 2, but Overwatch is what made him famous. In 2016, Hawelka founded IDDQD (not to be confused with the player of the same name), an Overwatch team that transformed into the award-winning Team EnVyUS, and ultimately became the Overwatch League's Dallas Fuel. In 2017, Hawelka transitioned into a coaching role, securing a job with Team Liquid shortly before the organization disbanded its Overwatch program. Still, Hawelka landed on his feet: Liquid was so impressed by Hawelka's coaching abilities that the organization moved him to their League of Legends team.

Unfortunately, complications resulting from tonsillitis took Hawelka's life far too early. In the aftermath, Blizzard is doing its best to make sure that Hawelka, while gone, is not forgotten. Shortly after Hawelka's death, Blizzard unveiled the Overwatch League's Dennis Hawelka Award, which will honor the player who who has "the most positive impact on the community" each season. Hawelka "changed countless lives for the better, in game and out," Blizzard says. "His intelligence, generosity and friendship will never be forgotten."

Steve Kordek, the pinball wizard

Arcades existed well before video games—almost a hundred years before video games, in fact. Before arcades were filled with flashing screens and pixelated heroes, they were populated with all kinds of mechanical amusements, including shooting galleries, fortune telling machines, and lots of pinball.

In fact, historians claim that without pinball, video arcades (and, consequently, the video game industry) wouldn't exist. So if you're nostalgic for the arcades of the '70s or '80s or you happen to be a pinball fanatic, you have one man to thank: Steve Kordek, who created the modern pinball machine. Kordek didn't invent pinball—the game dates back to the 1800s—but he was the man who decided to put two flippers on the bottom of the machine, transforming pinball from a game of luck into a game of skill. Pretty much every pinball machine that's come out since has used Kordek's design.

Kordek, a former forest ranger, designed over 100 pinball machines before he retired in 2003, including Space Mission, Grand Prix, Pokerino, and Contact, which told the story of the first meeting between humans and aliens. That's not bad for a man who got his job by accident (he wandered into the lobby at Genco, an old time pinball machine manufacturer, in order to escape a rainstorm), and claims that he never saw a pinball machine before he started working on them. Kordek's been compared to seminal film director W. D. Griffith for his contributions to the pinball community, and allegedly loved the game wholeheartedly right up until his death in 2012.

Corey Gaspur, the lead designer of Anthem

After working at video game development company BioWare for nine years, Corey Gaspur was named lead designer on Anthem, BioWare's upcoming Destiny-like shooter.

It was a well-deserved promotion. After cutting his teeth on BioWare's collaboration with Sega, Sonic Chronicles, Gaspur designed levels for Dragon Age: Origins and Mass Effect 2. The Mass Effect 3's combat system, which many critics call out as one of the game's biggest highlights, is a Gaspur creation. He also contributed to other Electronic Arts games as a consultant, lending his expert advice to Star Wars Battlefront and Mirror's Edge: Catalyst. Anthem was set to big Gaspur's biggest game yet, and by all indications, he was going to nail it.

In July 2017, however, tragedy struck. Just a few weeks after Anthem made its big public debut at E3 2017, the young designer passed away, leaving a gaping hole in BioWare's development team. Anthem is still slated for a 2018 release, but sadly, Gaspur won't be around to see it through to completion. In an official statement, BioWare commemorates Gaspur as "a talented designer and an even better person," and notes that you can donate money to help Gaspur's young son, Cain, at YouCaring.

Gunpei Yokoi, the creator of the Game Boy

Gunpei Yokoi is responsible for some of Nintendo's biggest hits–and its biggest flop. Yokoi started working at the Kyoto-based company in 1965, when it still made playing cards, taking on odd jobs like janitor and factory worker. But Yokoi's time at the bottom didn't last very long. In his spare time, Yokoi developed a mechanical arm toy, which quickly caught the eye of Nintendo president Hiroshi Yamauchi. Nintendo named the device the Ultra Hand and rushed it to market, and 1.2 million sales later, Nintendo was a toy company—and Yokoi one of its rising stars.

Inspired by a bored businessman he saw playing with a digital calculator, Yokoi created Nintendo's Game & Watch line, a series of portable games that introduced the D-Pad controller to the masses. He invented the Nintendo's robot peripheral, the R.O.B., produced Shigeru Miyamoto's earliest titles (you know how Mario doesn't die when he falls from high ledges? That's a Yokoi contribution), and fathered the Game Boy, the third-best selling game console ever. He's also responsible for some of the Game Boy's best games, including Super Mario Land and Dr. Mario, as well as the Virtual Boy, Nintendo's ill-fated VR console.

More than all that, however, Yokoi also coined Nintendo's driving philosophy. In the book Yokoi Gunpei Game House, Yokoi describes his approach to development as "Lateral Thinking with Seasoned Technology." Instead of focusing on cutting-edge tech, Yokoi tried to find ways to use established (and therefore less expensive) components in new and fun ways. Gameplay, Yokoi contends, is more important than technology—see, for example, the Game Boy's green and black screen, which made it cheaper and more accessible than the full-color Sega Game Gear.

Yokoi died in a car crash in 1997, but his influence and legacy has lived on. The Nintendo Wii and the Nintendo Switch are significantly underpowered compared to the competition, but they're still unparalleled successes. Basically, without Yokoi, Nintendo as we know it wouldn't exist.