The Untold Truth Of Super Mario

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Face it: Super Mario is weird. He's a fat Italian jack-of-all-trades who lives in a land populated by sentient fungus, but ruled by a young human woman. His arch-nemesis is a turtle and his best friend is a dinosaur. He's good at every single sport he tries, his hat possesses people (and things), and sometimes he turns into a flying raccoon.

Behind the scenes, Mario's world is just as wacky, but there's a method to the madness—you just have to dig deep to find it. Over the years, the twisted minds at Nintendo managed to create one of the most beloved pop culture characters of all time, but it took a lot of work.

Mario wouldn't exist without Popeye

Donkey Kong, the game that introduced Mario to the world, almost starred a totally different cast of characters—very famous ones. While Nintendo's been making video games since the mid-'70s, by the early '80s the company had yet to produce a big hit. So company president Hiroshi Yamauchi gave Nintendo's games team a simple mission: "Make games that sell more!" (Not a direct quote.)

One of Nintendo's young artists, Shigeru Miyamoto, went straight to work. At the time, Nintendo made more than just video games—they made playing cards, too—and had previously secured the rights to Popeye. As Miyamoto explains in an interview on the Nintendo website, Miyamoto proposed a number of different Popeye-related titles. His boss, Game Boy designer Gunpei Yokoi, took the ideas to management. Before long, the Popeye game was greenlit.

But shortly before launch, Nintendo lost the Popeye license–Miyamoto can't remember why–and Miyamoto decided to simply swap in his own characters. Instead of the grumpy sailor Popeye, the new game starred a mustachioed blue-collar worker named Jumpman who'd later be renamed Mario. Donkey Kong took the place of Popeye's muscular rival, Bluto, while the skinny damsel-in-distress, Olive Oyl, became Pauline (or, as she's known in Japan, Lady).

Donkey Kong went on to be a massive success, making both Miyamoto and Mario's career. A couple of years later, Miyamoto finally got to make a Popeye game, too—which, ironically, critics dismissed as a simple Donkey Kong clone.

Mario isn't actually a plumber (anymore)

With all of that princess-saving he has to do, Mario doesn't really have time for a day job. And yet, for years, he's been known as a plumber. In 2017, that changed. In a promotional blurb on Nintendo of Japan's website (translated by Kotaku, among others), Nintendo revealed that Mario's pipe-fixing days are behind him. While Mario "seems to have worked as a plumber a long time ago," Nintendo says, he's currently occupied playing sports, doing "everything cool," and (presumably) keeping the Mushroom Kingdom safe.

In fact, Shigeru Miyamoto tells USA Today that Mario's job has never been set in stone. "The scenario dictates his role," Miyamoto says. In Mario Bros., he and Luigi are plumbers because they're working underground and because the stage is surrounded by pipes. But in Donkey Kong, which takes place on a construction site, he's a carpenter, a role he'd reprise on the Super Mario Maker box art (pictured above). In Mario vs. Donkey Kong, he manufactures toys. He's a chef in Yoshi's Cookie, a referee in Mike Tyson's Punch-Out!!, and a particularly hapless soldier in Mario's Bombs Away, a Game & Watch title.

Mario was originally going to ride on rockets and shoot lasers

Super Mario Bros. didn't start as a side-scrolling game—or even a Mario title. As some of the original developers explained in one of Nintendo's Iwata Asks features, early prototypes involved a blank square that moved around a non-scrolling screen. The square couldn't even jump. Mario only became the star after a developer looked at Nintendo's sales figures, realized that Mario Bros. was selling well, and decided to repurpose the character for the new game.

Even then, Mario's world wasn't locked down, and the Mushroom Kingdom went through many iterations before becoming the world that we all know and love. In another installment of Iwata Asks, some of the Super Mario Bros. development team unearthed the game's original design documents and made a number of surprising discoveries, including that Mario was originally going to kick bad guys while on the ground, and then shoot them with a "beam gun" while cruising through the air on a rocket ship.

Eventually, Miyamoto and his team turned the rocket into a cloud, and then abandoned the flying sections entirely. Still, both of those ideas resurfaced in later Mario games. In Super Mario Land, Mario's first portable outing, he pilots a rocket-bearing plane called the Sky Pop, while Mario and his friends wield high-tech weapons in 2017's Mario + Rabbids Kingdom Battle.

Japan has a totally different Minus World

Super Mario Bros. die-hards in America are familiar with the game's mysterious, unplanned Minus World, which doubles as one of the most famous glitches in gaming history. By jumping through a pipe in Super Mario Bros.' World 1-2, Mario can travel to an inescapable water level. You can't defeat Minus World—it just loops over and over—and the only way to escape is to run out of lives or hit reset.

In Japan, however, Super Mario Bros. was ported to Nintendo's Family Computer Disk System, an add-on for the Famicom (the Japanese edition of the Nintendo Entertainment System) that stored games on floppy disks, not cartridges. In that version, you still reach Minus World in the same way, but what you find waiting for you on the other side is both entirely new and also actually beatable.

The Computer Disk System Minus World begins with a stage that's exactly like World 1-3, except that it's submerged underwater and filled with creepy hovering Princess Peach sprites, a headless King Koopa, and a different color palette. Minus World -2 is a retread of World 7-3, while Minus World -3 is a glitched out version of level 4-4 that adds flying Bloopers, Mario's squid-like foes. Beating the third and final stage returns players to Super Mario Bros.' title screen. If they start a new game, it'll be exactly like Super Mario Bros.' hard mode, which is unlocked by beating the game the normal way.

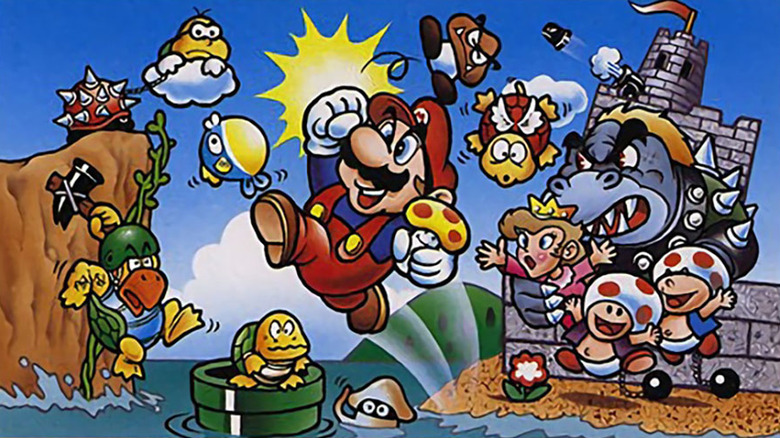

Shigeru Miyamoto drew Super Mario Bros.' box art

In America, the Super Mario Bros. box art shows Mario leaping over a lava-filled pit (possibly to his doom). In Japan, the box art is a hand-drawn tableau featuring Mario's supporting cast. Toad, the Koopa Troopas, Princess Peach, and Bowser are all there, although they look a little different than you might expect.

As it turns out, that image was hand-drawn by Mario creator Shigeru Miyamoto himself. Miyamoto wanted to be a manga artist when he was young, although he decided to study industrial design after concluding that the competition in manga was too stiff. When he first started working at Nintendo, he was employed as an artist, producing art for the sides of arcade cabinets. When it came time to give Super Mario Bros. some official packaging, Miyamoto wanted to hire a professional manga artist, but there wasn't enough time. So, he produced the art himself.

Inspired by the anime movie Alakazam the Great, which is based on the classic Chinese novel Journey to the West, Miyamoto imagined Bowser as a monstrous ox-like creature. And his take on Princess Peach is a lot less feminine than you might be used to. The Princess, King Koopa, and many other characters didn't assume their more familiar forms until Nintendo hired animator Yoichi Kotabe, who worked with Miyamoto to produce the official Mario designs—and helped convince Miyamoto that Bowser should be a reptile like his minions, not an unrelated mammal.

The first Super Mario Bros. sequel wasn't made by Nintendo

Most fans know there are two versions of Super Mario Bros. 2. The Japanese sequel, which came out in 1986, was deemed too difficult for US players. As a replacement, Nintendo added Mario characters to a game called Yume Kōjō: Doki Doki Panic and released it stateside as Super Mario Bros. 2. The original Super Mario Bros. 2 wouldn't make it to the west until 1993, when Nintendo included it in Super Mario All-Stars as The Lost Levels.

And yet, neither of those games are actually the first sequel. That honor lies with Super Mario Bros. Special, a long-forgotten version of Super Mario Bros. developed by Hudson Soft–not Nintendo. Thanks to a licensing agreement, Hudson had the rights to bring Nintendo games, including Super Mario Bros., to other platforms, like the PC-8801 and the Sharp XI personal computers.

But neither of those machines are as powerful as the NES. In order to make the port work, Hudson Soft rebuilt Super Mario Bros. from the ground up. The final product is a totally different game. The levels don't scroll as the players move. A limited color palette makes the Mushroom Kingdom super-ugly, and the 32 brand-new levels are fleshed out with new power-ups and enemies plucked from Mario Bros. and Donkey Kong. The physics are janky and, by all indications, Super Mario Bros. Special isn't very fun. But that doesn't negate its historical value. It just makes it easy for anyone but hardcore fans to skip.

The Super Mario Bros. movie has an official (sort of) sequel

If you haven't seen it, take our word for it: the Super Mario Bros. movie isn't very good. Its stars hated it. So did critics, the film's producers (who demanded last-minute script changes after realizing that the film wasn't going to look anything like the video games), and judging from the box office receipts, audiences too.

Despite the on-set chaos (allegedly, co-star John Leguizamo, who played Luigi, only survived the shoot by drinking heavily), the filmmakers optimistically ended the film on a cliffhanger, with Princess Daisy returning from Dinohattan, flamethrower in hand, to enlist the Mario Bros.' help. Given the film's poor reception, a sequel was never filmed. However, in 2010, two fans—believe it or not, the movie has a few—interviewed co-writer Parker Bennett for the Super Mario Bros. The Movie Archive and joked about a teaming up for a sequel. Afterwards, discussions became more serious, and Bennett helped the duo come up with the plot for Super Mario Bros. 2.

It's not a real movie, of course. Writers Steven Applebaum and Ryan Hoss don't have the rights on the budget to film a fully-fledged sequel. But, with help from artist Eryk Donovan and letterer Jaymes Reed, they were able to transform their pitch into a webcomic that picks up right where Super Mario Bros. left off. It's totally unauthorized, and yet, with Bennett's input, also basically canon.

Sadly, the comic may never be finished. While Applebaum and Hoss' comic gets about halfway through the story, production seems to have stopped sometime in 2015. Around the same time, Applebaum and Hoss launched a (now-deleted) Indiegogo campaign dedicated to raising money for an officially licensed comic book adaptation, but that stalled out at $60, leaving most of the $1050 goal out of reach.

Jason Bateman and Alyssa Milano starred in a live-action Mario adaptation

Before the Super Mario Bros. flick bombed at the box office, seeing Mario in live action was still pretty common. Skits before and after the Super Mario Bros. Super Show revealed the real-life adventures of Mario and Luigi as they plunged pipes in Brooklyn, and a one-off broadcast starring Jason Bateman and Alyssa Milano brought Mario, Luigi, and the rest of the gang to life as plucky, heroic...ice skaters.

Yes, seriously. In ABC's 1989's Ice Capades special, which also featured an appearance from Mattel's Barbie, Bateman plays the self-proclaimed "video prince" who mainsplains Super Mario Bros. to Milano's clueless noob. Before he gets too far, however, the NES they're using contracts a virus, which unleashes Bowser's minions on the real world. King Koopa, played by Christopher "Mr. Belvedere" Hewett, raps about his evil plans while commanding his forces. In response, Princess Toadstool summons Mario and Luigi to fight back. They win, of course, and Milano ends the segment by claiming that she beat the game.

Despite the shots of smiling children, the entire six-minute video is odd and unsettling, thanks largely to the off-model mascot-style costumes that the Ice Capades skaters wear while playing Nintendo's characters and the muddled choreography. Still, if you want to see what things were like before Nintendo was too strict about how its characters were portrayed, it's worth a watch. At the very least, it's short.

Nintendo can't use characters from Super Mario RPG

Super Mario RPG: Legend of the Seven Stars is one of the very first games that tries to make sense out of Mario's abstract, wacky world. That's a daunting task, but somehow, developer Squaresoft (now Square Enix) nailed it, especially when it comes to the characters. Mario is as a silent but heroic protagonist, Princess Peach and Bowser play their sidekick roles perfectly, and two new characters—the cloud prince Mallow and Geno, a possessed doll—fit in perfectly alongside the Mushroom Kingdom's more traditional citizens.

And yet, surprisingly, neither Mallow nor Geno have made a major appearance in a Mario game since. Super Mario Odyssey proves that, when nostalgia's involved, no cut is too deep for Nintendo, and these were relatively popular characters. Their omission from future Mario games is baffling–unless, of course, Nintendo doesn't actually own them.

Geno cameoed in a minigame in Mario & Luigi: Superstar Saga, Super Mario RPG's spiritual successor, but the game's end credits note that Square Enix owns the copyright to the character (Geno was cut from Superstar Saga's 3DS remake). Similarly, director Masahiro Sakurai wanted to include Geno in Super Smash Bros. for Nintendo 3DS and Wii U–but wasn't allowed to. By all indications, Square Enix owns Mallow, Geno, and the rest of Super Mario RPG's original characters. Nintendo can use them, but they need Square Enix's permission first. So don't expect to see them pop up in Nintendo games anytime soon.

Super Mario 64 was inspired by Croc: Legend of the Gobbos

Super Mario 64 is one of the most important and beloved video games of all time. Croc: Legend of the Gobbos made a big splash at launch, with decent reviews and pretty good sales, but it's largely forgotten today. And yet, according to one game industry executive, without the latter we may never have gotten the former.

Nintendo owes a lot to Argonaut Games, the company behind Croc. In the early '90s, Argonaut worked with Nintendo to develop the Super FX chip, alongside the chip's signature game, Star Fox. Together, they also developed Star Fox 2, which contained 3D platforming elements that programmer and co-creator Dylan Cuthbert says influenced Super Mario 64. Similarly, Argonaut founder Jez San tells Eurogamer that the company pitched Nintendo a Yoshi-themed 3D platformer a few years before work on Super Mario 64 really started.

But Nintendo cancelled Star Fox 2 at the last minute, and passed on Yoshi entirely, only to go on and make Super Mario 64, a game very similar to Argonaut's prototype. Later, San claims that Miyamoto "thanked us for the idea to do a 3D platform game." Argonaut retooled the Yoshi title and released it as Croc, but it was too little, too late. Super Mario 64 beat Croc to the market by almost a year, cementing its status as the first truly successful 3D platformer.

These days, Mario and Nintendo continue to flourish. The Switch, Nintendo's latest console, moved over 10 million units in its first nine months on the market, thanks largely to the very Mario 64-like Super Mario Odyssey. Argonaut, meanwhile, closed its doors in 2005, while Croc is little more than an afterthought in the annals of video game history.