The Shady Side Of Konami

Much like Nintendo, Konami's early days reach far back beyond the introduction of console gaming. The company started as a jukebox rental company before its founder, Kagemasa Kozuki, moved Konami into the recently birthed world of arcade games in 1973. Legendary games like Frogger soon followed, and before long, Konami was making games for the Atari 2600 and, later, the Nintendo Entertainment System. Konami's jump into the console space kicked off a legacy that has helped shape the gaming landscape we know today, giving us instant classics like Metal Gear, Contra, and Castlevania, along with the "Konami code" still used by titles to unlock secrets and uncover easter eggs.

But it hasn't been all sunshine and rainbows with Konami. Like a large ship, there's the sheen and grandeur visible from above the surface; the majesty the industry attaches to a stalwart that's been around since the start. But there's also that "seedy underbelly;" the unseemly quilt of ugly sea things attached to the hull that no amount of scraping can displace. Some might believe Konami has been a stand-up company for most of its existence, with some of its more egregious infractions coming only in the Metal Gear Solid V era. But digging into the game giant's past, it's apparent that their questionable behavior isn't a recent trend.

Below, we'll take an up-close look at Konami and shed some light on some of the shady practices the company has engaged in over its long history.

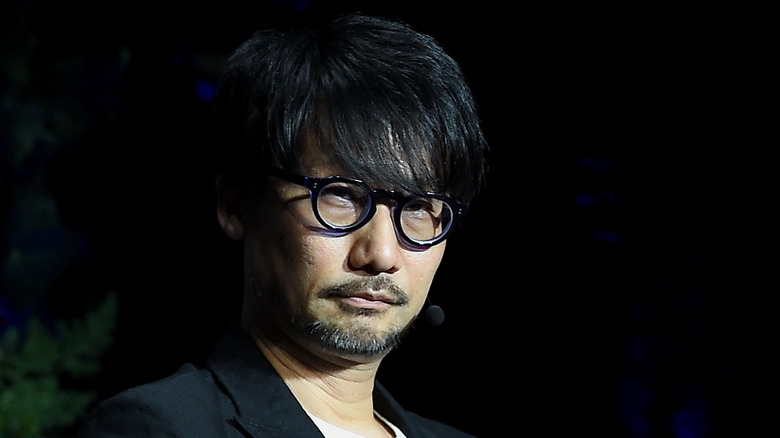

Separating from Hideo Kojima in the ugliest, most childish way possible

Hideo Kojima is the design wizard behind the Metal Gear franchise, taking the series from its 8-bit roots all the way through the rise of 3D and, eventually, the arrival of high-definition gaming. Then Metal Gear Solid V happened. The game, which was first teased in 2012, appeared to cause a lot of internal strife between Konami and Kojima Productions. Development of the title was done on a brand new engine and rang up costs to the tune of $80 million. That exorbitant amount kicked off an internal power struggle between Kojima and Konami that did irreparable damage to their business relationship.

Much of what happened next occurred out in the open. Konami, during a company restructuring effort, renamed Kojima Productions Los Angeles to Konami Los Angeles Studio. It started to wall off corporate communications access to Kojima Productions staff. Before the release of Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain, Konami removed the phrase "A Hideo Kojima Game," as well as the Kojima Productions logo, from the box art. And more confusing yet: Konami continued to insist all along that Kojima was still very much a part of Konami.

But Konami was full of it, and the stunt it pulled at the 2015 Game Awards turned much of the gaming community against the company. The Phantom Pain won two awards, but when it came time to hand out the trophy for Best Action/Adventure Game, a somber Geoff Keighley had to tell the crowd that Konami would not let Kojima accept it.

Kojima's departure from Konami was later made official on December 15, 2015.

Removing P.T. from the PlayStation Store

Interwoven into all the madness attached to The Phantom Pain is the story of P.T., a short, surprise PlayStation 4 demo unveiled by Konami at Gamescom 2014. Fans were treated to a trailer of the demo, showing genuinely frightened gamers playing and screaming their collective heads off. But what exactly P.T. was remained a mystery until several hours after it hit the PlayStation Store and smart puzzle solvers cracked the code.

We know now, with the benefit of hindsight, that P.T. was a "playable teaser" for Silent Hills, a new game in the Silent Hill series. It was a collaboration between Hideo Kojima and movie director Guillermo del Toro — two men who admire each other greatly — and was set to star The Walking Dead's Norman Reedus as the main protagonist.

But sadly, the Kojima and Konami fallout occurred. Konami adopted — as del Toro put it — a "scorched-earth" policy with how it handled the fates of both P.T. and Silent Hills. Silent Hills was canned in early 2015, shortly after all of the Phantom Pain-related shenanigans began.

And as for P.T.? Konami somewhat shockingly announced it would also remove that title from the PlayStation Store.

The reaction wasn't pretty. P.T. had received wide critical acclaim, with some even listing it among the best games of all time. And removing it from the PlayStation Store meant those who had it could play it, but those who didn't would never be able to download it again. There was no real reason for Konami to pull the teaser offline, other than to be vindictive.

Running a ridiculous boot camp for Metal Gear Solid V reviewers

It may come as a shock to website commenters and the Twitter brave, but game journalists really do try to offer a fair, critical look at the games they review. No one is "in Activision's pocket," for instance, and for the most part, publishers play ball and give reviewers ample time to review a game without applying any pressure. There's definitely some crunch — where reviewers stay up all hours of the night trying to play through and write a piece before deadline — but that crunch at least happens on the reviewer's terms.

That's what makes the "boot camp" review process applied to Metal Gear Solid V: The Phantom Pain so stunning. According to those who took part, they were put up in a hotel where they were given strict 9am-to-5pm blocks to play The Phantom Pain. The game could not be played outside those hours, and when time was up, time was up.

If you assume every second of that time was spent playing the game, that only gave reviewers a total of 40 hours to get through The Phantom Pain, or at least play enough to formulate an opinion. And if you look the game up on HowLongToBeat, you'll find it takes players, on average, 45.5 hours to get through the story alone.

The Phantom Pain wound up being a critical success, but it can't be said for certain that the limited amount of playtime didn't affect the reviews that came out of the event. Several outlets complained about the "boot camp" afterward, and at least from Konami, we haven't seen one since.

Charging for save slots in Metal Gear Survive

Thanks to its very public spat with Hideo Kojima, Konami found itself on very thin ice with fans of the Metal Gear franchise. So you would think the company's main focus when bringing out a new title in the series would have been to tread lightly, deliver a good game, and above all else, avoid controversy.

Sweeping aside the fact that Metal Gear Survive, released in early 2018, isn't a traditional Metal Gear game, Konami opted to embed some questionable microtransactions into the experience. The game sells a currency called "SV Coins" for real money, enabling players to purchase add-ons that enable faster leveling and additional load outs for characters. These are a bit gross by themselves. But the most striking, audacious microtransaction by far is the one that unlocks an additional save slot.

This particular item got the most attention from the press, and rightfully so. An extra save slot, which most games include as a matter-of-fact feature, requires one Alexander Hamilton to be removed from your wallet. That's right — $10. Of course, you can log in every day for your 30 SV Coin bonus and rack up enough currency to buy a slot after 34 days, but that's assuming you don't spend your coins on anything else.

And there's another kicker: you can't buy just the 1,000 SV Coins required for that save slot. Purchasing $10 worth gets you 1,150 SV Coins, in what looks like an attempt to trigger PTSD in gamers who remember Microsoft Points.

Blacklisting critical media outlets

Konami's relationship with the gaming press can best be explained using a Facebook status: it's complicated.

On one hand, there are plenty of video game news writers and critics who have grown up on Konami games and look upon the company with fondness. Some include games like Metal Gear Solid among their favorites. And it's hard not to acknowledge the influence Konami has had on the industry as a whole.

On the other hand, however, Konami has at times displayed a hostility toward the media that covers it. Look no further than the above video created by former IGN editor Colin Moriarty, who claims that — unbeknownst to him at the time — a Konami blacklist of IGN prevented him from doing his job at an industry event.

And speaking of Castlevania, it was IGN's review of Castlevania: Lords of Shadow that apparently earned it Konami's scorn. The game received a "Good" score from the website — a 7.5. However, Konami took it as a slight. So when it came time to see Lords of Shadow 2 at Gamescom 2013, the publisher struck back. Moriarty was not able to see Lords of Shadow 2 at the event, and a mishmash of blockades and canceled appointments continued to confront IGN over the course of the year. Eventually the outlet told Konami it would have to tell readers why its Konami-related coverage lagged behind its competitors.

Soon after, Konami dropped IGN from its blacklist.

Attempting to silence a critic with a DMCA takedown

When it comes to criticism, Konami's transgressions aren't limited to the credentialed press. The company also doesn't take kindly to those who speak ill of it on social media platforms, if you count this story about a YouTube creator who produced a video about the Konami/Kojima situation.

The creator's name is George Weidman, but he's better known as "Super Bunnyhop." In early 2015, Mr. Bunnyhop uploaded a video that detailed the ongoing feud between Kojima and his employer, using what he stated was information from an unverified inside source to offer new revelations on the matter.

But then something weird happened. The video was taken down from YouTube, showing it was "no longer available due to a copyright claim by Konami Digital Entertainment Co. Ltd." Needless to say, the press caught wind, and interest in the video increased.

Konami, it seemed, had never heard of the "Streisand Effect."

But the story gets weirder still. Not long after the video was taken down because of Konami's claim, it was reinstated. Weidman was informed that YouTube had concluded there was no copyright violation. And in a separate message to Konami, YouTube schooled the company on fair use.

Engaging in unfair business practices

When it comes to sports league licenses, exclusive agreements aren't an uncommon practice. The Madden franchise, for instance, has held an exclusive NFL license for over a decade. Konami entered into such an agreement with The Professional Baseball Organization of Japan way back in the early 2000s, but that particular arrangement came with a twist: Konami would exclusively hold the license and manage licensing to other software companies. This meant that Konami would be in charge of okaying others to use the PBOJ's license — even when those companies were going to create competing products.

Sounds like a recipe for disaster, right? It was. Fast forward to 2003, and Konami was hit with a warning from Japan's Fair Trade Commission, which stated that Konami had quite possibly violated the Antimonopoly Act. A press release from the aforementioned commission states that Konami "engaged in conduct that delayed the conclusion of sub-license agreements with certain software developers, or delayed the sale of new professional baseball game software products by those software developers or caused them to abandon the development of such software."

In essence, Konami didn't want the competition, so it sat on approving licenses for several software companies until they either delayed their projects or canceled them altogether. Lame, Konami. Lame.

Operating a nanny state work environment

We've all, at one time or another, heard stories about nightmare jobs. They might have been about a company that works its employees long hours for very little pay, or a supervisor who is constantly breathing down the necks of employees.

What surfaced about the work environment at Konami in 2015, however, blows all of those stories out of the water.

Nikkei, a Japanese news site, received a boatload of information about the draconian management practices that were taking place inside Konami. And once it was able to corroborate the stories with inside sources, it ran a story that laid bare the awful things Konami was doing to its most talented employees.

To start, the company used email addresses comprised of mixed letters and numbers, and reassigned those addresses on a regular basis so recruiters wouldn't be able to send feelers for job opportunities. Next, it kept a close eye on lunch breaks and essentially shamed those who came in late via company-wide email. And employees were constantly monitored via video surveillance to ensure that, were they to get up and go somewhere in the office, they did so as quickly as possible.

There's one offense that really takes the cake, though. The company would reportedly reassign employees they didn't like to brand new, completely unrelated jobs elsewhere in the company. A gifted programmer, for example, could suddenly find themselves working as a janitor. Or a marketer could suddenly be shifted into a factory assembling pachinko machines.

We hope those practices have ceased, but we have no evidence that they have.

Demoting an employee because she gave birth

If the last section about Konami's toxic work culture wasn't enough for you, there are even more examples of ways the company has mistreated its employees and acted with suspect motives. One of those examples involves Yoko Sekiguchi, who worked in licensing for Konami.

Sekiguchi became pregnant in 2008 and took maternity leave from Konami to give birth and, afterward, care for her newborn baby. When she returned to work in early 2009, however, Sekiguchi was informed that she had been demoted from the position she held. The move reduced her monthly income roughly $2,000 — not exactly the news someone wants to hear after having a child.

When Sekiguchi pressed her superiors for an explanation as to why she'd been demoted, she was told it was because of the "burden" she now had: her baby.

Refusing to let the move go without a fight, Sekiguchi sued Konami for $422,000, citing "discrimination" due to her status as a new mother. The case took a long time to reach its conclusion — nearly 3 years — but when it did, Sekiguchi emerged victorious.

Unfortunately, she was only awarded $12,000. But at least she could put the situation behind her, hit the job market running, and use the experience she gained at Konami to land a new gig, right?

Blackballing its former employees

Konami seems to have its bases covered when it comes to demonstrating ill will toward employees, and that treatment doesn't end when someone quits.

In 2016, it was reported by Nikkei that Konami had, on several occasions, blackballed former employees by preventing them from landing jobs elsewhere. In one instance, an ex-Konami employee was unable to get hired by a Japanese health insurance company because the chair of the company's board was also a Konami board member. In another instance, the company actively lobbied a TV network not to hire anyone who'd previously worked at Konami.

And that's not all. Konami alumni are reportedly not even allowed to mention the company on their resumes. As one former employee put it, "If you leave the company, you cannot rely on Konami's name to land a job."

It seems, then, that the best thing someone can do for their career is never work at Konami, period.

Did Konami rip off an American music game?

Yes, Konami makes games for consoles, but Konami also has significant resources dedicated to making good old-fashioned arcade cabinets. In 2015, Konami released Museca, a new music game. The internet, however, pointed out that Museca didn't look very new. Rather, Museca seemed like a new version of the American music game Neon FM. Sure, the button setup is different, and Museca's button can be spun as well, but the resemblance is so striking that people were calling Museca "reversed Neon FM."

Konami's copycat act is fairly ironic, considering the company's history of suing other companies that produce music/rhythm games that look like theirs. In 2008, Konami filed a lawsuit against Pentavision Global, the now defunct producer of the DJMAX series, because they claimed that DJMAX was too similar to their Beatmania series. The copyright infringement case was settled out of court, and this was one of the reasons why Pentavision Global went out of business. We're willing to bet that Konami wouldn't like it if Neon FM's Unit-e Technologies sued Konami for copyright infringement over Museca.

Konami focuses on gambling, not gaming

It's not a well-known fact in the West that Konami is a prolific producer of pachinko machines. Pachinko machines are essentially one part pinball machine, one part slot machine. They don't have to involve gambling, but they often do. Konami has produced several pachinko games based off of their most famous series. Some fans have taken exception to the fact that the company seems willing to turn a beloved action game like Castlevania into an "Erotic Violence" (emphasis on the erotic) pachinko machine before considering making new games.

When Silent Hills was canceled upon Hideo Kojima's exit from the company, many wondered when we would be getting a new Silent Hill game. Konami has said that it will happen, but right now the company seems more focused on making games for gambling. Silent Hill will be getting a new game ... in the form of a slot machine. Fans have felt that Konami is mistreating their IP, making games that make quick cash rather than AAA continuations of beloved franchises.

Pay to win is our future

Konami makes more money from its pachinko machines than it does from its games. And its mobile games make millions more than its traditional, AAA console games. This has served to convince the higher ups at Konami that mobile is the future. According to Konami president Hideki Hayakawa, "Mobile is where the future of gaming lies. With multiplatform games, there's really no point in dividing the market into categories anymore. Mobiles will take on the new role of linking the general public to the gaming world."

There's nothing wrong with mobile games or focusing on developing mobile games. Former Konami fans have, however, taken issue with the fact that Konami's strategy centers on ignoring its historic franchises in favor of cheap-to-make, pay-to-win mobile games. Hayakawa himself said that the company needs to focus on selling items and features. Maybe this is how the disastrous $9 save slot in Metal Gear Survive happened.